Joel Salatin argues that it is possible to have sustainable and economically productive farms by insourcing rather than outsourcing. It is all about relationships, he explains. The industrial world is at farming crossroads, facing an inquisition, caught in arguments between orthodoxy and heresy. “I’m a heretic,” he grins, speaking at a meeting of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Agroecology on May 1.

“Is it just possible that our grandchildren will laugh at some of the things we believe today?” he adds with a twinkle in his eye. At one time the earth was believed to be flat; two centuries ago medicine was practiced with leeches and bloodletting; slavery was once thought of as normal.

“Is it just possible that our grandchildren will laugh at some of the things we believe today?” he adds with a twinkle in his eye. At one time the earth was believed to be flat; two centuries ago medicine was practiced with leeches and bloodletting; slavery was once thought of as normal.

“Thirty years ago, it was standard practice to feed dead cattle to living cows. Today we know differently. So what other orthodox myths should we be questioning? Right now it’s ‘we’ve gotta feed the world’ as if the industrial world knows best.”

Salatin recalls attending a Slow Food convivium in Turin and made an effort to attend meetings organised by the African delegations, where he heard the same basic message. Those present had their own abundant resources and industrial farming could “butt out.”

Pasteur’s discovery of bacteria cast germs in the role of “bad guys” without distinction: something we now know to be overstated. “So what does modern agricultural orthodoxy do to protect society from pathogens these days?” The wisdom of concentrating single species populations into close confinement and feeding them prophylactic antibiotics flies in the face of long established scientific knowledge.

Salatin’s own experience of farming started in 1961, when his father took on a 500-hectare farm in Virginia. Salatin senior calls in extension workers from both state and federal agencies to ask their advice, which consists of taking out long term loans to build a silo and grow low-margin commodity cereal crops for export. As an economist, his father avoids the treadmill paradigm and built up the local food business that is now Polyface.

Taking questions after speaking, he confirms that he neither takes subsidies nor advocates them, believing instead that a sustainable farm is built on a living wage. “Cheap food stimulates poor farming,” he explains, adding: “There’s enough money in the system.”

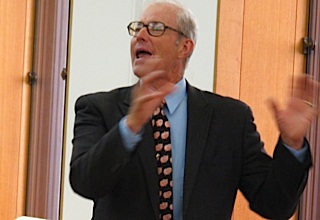

He is an engaging speaker, not given to hiding behind a lectern. He has too much to say to be able to do justice to his thinking in a single sitting. Fortunately, he has written a number of books to argue his good-natured philosophy.

Readers in the US can order his books directly from the website but international orders have often suffered damage in transit. European readers will need to trawl online booksellers to obtain copies of his latest book Folks, This Ain’t Normal: A Farmer’s Advice for Happier Hens, Healthier People, and a Better World.