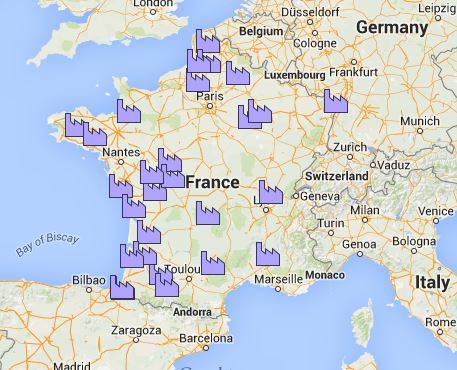

Where would you expect to find a completely automated dairy factory, where 280 cows are milked by four robots overseen by just two staff? The Breton town of Bréhan is home to this French factory farm, one of 27 listed in an online map published by Confédération paysanne (Conf’). The Conf’ has identified some of the most notorious factory-scale units so far in a list that is already extensive, with livestock units holding thousands of finishing cattle and thousands of piglets.

Where would you expect to find a completely automated dairy factory, where 280 cows are milked by four robots overseen by just two staff? The Breton town of Bréhan is home to this French factory farm, one of 27 listed in an online map published by Confédération paysanne (Conf’). The Conf’ has identified some of the most notorious factory-scale units so far in a list that is already extensive, with livestock units holding thousands of finishing cattle and thousands of piglets.

One pig unit has applied to expand its herd to 3,000, despite being located in the middle of a Natura 2000 zone with an ecology that is home to flora and fauna of scientific interest. If the project at Loueuse (60) goes ahead, Cooperl will be spreading 5,000 cubic metres of slurry on 400 hectares. The public inquiry went in favour of the pig business Cooperl and the project will receive a final decision from the prefet in June.

A factory farm for 4,500 finishing pigs at Heuringhem (62) received planning permission in March 2013 but was stopped in October that year by the Administrative Tribunal. If it goes ahead, the slurry will be spread on wet land around the region’s water supply.

The extent to which different levels of French government is helping industrialised farming is flagrant: at Echillais, just outside the Charentais port of Rochefort, EUR 100m of public funding from local government is funding an incinerator that will heat 25 hectares of glasshouses growing tomatoes for Dutch company A&G Van den Bosch, part of a EUR 1.5 billion fresh produce group Greenery. The planning application received 810 adverse comments and six in favour, before the commissioner gave the project a green light.

The extent to which different levels of French government is helping industrialised farming is flagrant: at Echillais, just outside the Charentais port of Rochefort, EUR 100m of public funding from local government is funding an incinerator that will heat 25 hectares of glasshouses growing tomatoes for Dutch company A&G Van den Bosch, part of a EUR 1.5 billion fresh produce group Greenery. The planning application received 810 adverse comments and six in favour, before the commissioner gave the project a green light.

Power politics is never far away from money and the French countryside has its fair share of power-brokers. The pig-breeding unit at Trébrivan in Finistere has been closed twice by the administrative tribunal since it opened in 2012. On both occasions, the prefet issued an order allowing the unit to continue. Trébrivan houses 900 sows who collectively give birth to 23,000 piglets a year. The site generates 5,000 cubic metres of slurry and 7 tonnes of ammonia a year, spread over 480 hectares in a nitrate-sensitive area that is also the source of the region’s drinking water. The administrative tribunal recognises this public health risk, in a coastal area of France affected by agricultural runoff. The site is operated by SCEA Kerloann, a subsidiary of the cereals and biofuels group Sofiprotéol. The president of Sofiprotéol is none other than Xavier Beulin, head of the French national federation of farmers’ unions, the FNSEA.

The Conf’ caused a stir by launching the map on the eve of the Salon de l’Agriculture in Paris. The president of the republic opens the Salon de l’Agriculture, which is a national showcase for French agriculture, attracting half a million visitors during its 10-day span.

“It made a real impact,” Conf’ spokeswoman Elina Bouchet told ARC2020. “These are all extreme cases, for one or more reasons.” During their study, Conf’ researchers had trouble determining comparable average herd numbers at a holding level from official statistics because there are so many classifications for animals on or leaving a holding. “The only figure we could find was for dairy cows: 53.” What most people retain is an image of what farms should be rather than a defining number.

The Salon de l’Agriculture is an expression of how French agriculture wants to be seen and factory farming is not something that most of the French public wants to see. However, as the Conf’ points out, legislation in the French parliament at the moment, the loi Macron, tilts the table in favour of corporate interests. The Conf’ argues that articles 27-30, which cover the planning process, will make it harder to reverse any decisions on appeal. For instance, in the initial draft, demolition would be the sole prerogative of the judge heading up an administrative tribunal.

“Under the pretence of competitiveness, the government is choosing production agriculture without producers, to which should be added denial of concerns over the environment or climate,” the Conf’ warns.

More from Peter Crosskey

- 400m: the height of unfairness in Wales?

- UK government reverts to paper for basic payments

- 20,000+ march in London against climate change

- UK environment agency blocks Foston mega-pig farm plan

- Some progress on food waste in the UK

- Day One Good Food Good Farming Conference

- UK online-only basic payments deadline approaches…

- UK food bank users symptomatic of an isolated society

- Land Workers’ Alliance: small scale & family farming in UK

- Scots count cost of Westminster’s bodged CAP deal

- Brexit boobytrap for UK government

- Who is writing UK food policy?

- Rural Development in Wales Targets High Ground

- A growing interest in the UK for saving seed

- French mobilise against agri-industrialiation & TTIP/CETA