The role of farming in climate change mitigation is controversial and fraught. The UN COP (Conference of Parties) Climate Change process has tentatively introduced soil and carbon sequestration into its workings, via 4 pour 1000. However the role of particular agronomic practices involving livestock is under special scrutiny. Does livestock release more than it sequesters, or does the farming model matter? What about deep carbon storage? And how will policy makers work with new research and 4p1000?

What is 4p1000 – 4 pour 1000?

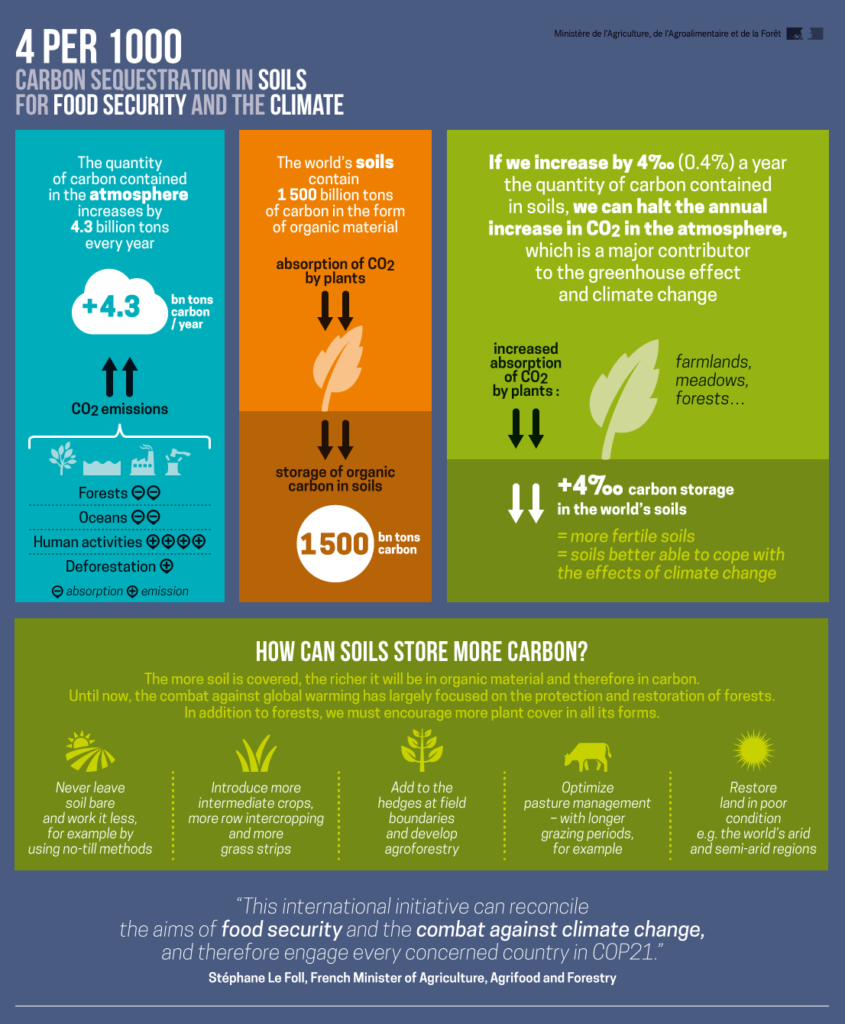

The role of The 4 per 1000 initiative “aims to increase the soil organic matter content and carbon sequestration, through the implementation of agricultural practices adapted to local environmental, social and economic conditions, as proposed in particular by the agro-ecology, agroforestry, conservation agriculture or landscape management.”

The name comes from the aim: increase carbon sequestration by four parts per 1000 per year for 20 years. (Pour comes from French, it is vaiously called 4P, pour or per 1000)

Governments and organisations around the world are partners in this, which was launched at COP22 in Marrakesh. Interestingly, it was not discussed at COP23 in Bonn.

We have covered the 4p1000 initiative here onARC2020 more than once, most recently with this article by Mario Catizzone:

We have covered the 4p1000 initiative here onARC2020 more than once, most recently with this article by Mario Catizzone:

Recent Research Critiques 4p1000

However recently published research has criticised the potential of initiatives like 4p1000. The mitigation potential of soil carbon management is “overestimated by neglecting N2O emissions” according to a February publication in Nature Climate Change.

This study, which specifically name checked 4p1000 in the opening line of its abstract, states that “soils can be a net sink of greenhouse gases through increased storage of organic carbon”. However “unless the use of fertilisers is adjusted to balance additional nitrogen inputs, any climate change mitigation benefit may be offset through higher nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions from soil” the researchers found. This impressively large study involved over 8000 sites around Europe.

Crop residue retention, lower soil disturbance and nitrogen-fixing cover crops were all beneficial for carbon sequestration, the researchers noted, but, importantly, only for a set period of time. Eventually – in a matter of two to four decades these practices eventually lead to net emissions. Because of this mitigation does occur for the first two to three decades, but, after that “nitrogen inputs should be controlled through appropriate management practices to counteract N2O emissions from soil.”

Another very recent publication is specifically critical of the 4p1000 approach. Using a site with soil data available from the mid 19th Century on, the Rothamsted research, published in Global Change Biology calls out 4p1000.

This publication does note other benefits of increases in soil organic carbon, but as Paul Poulton, lead author, put it, “the results showed that the “4 per 1000” rate of increase in soil carbon can be achieved in some cases but usually only with extreme measures that would mainly be impractical or unacceptable”.

An example given is “moving from continuous arable cropping to a long-term rotation of arable crops interspersed with pasture led to significant soil carbon increases, but only where there was at least 3 years of pasture in every 5 or 6 years”. This is also described as “uneconomic under present circumstances” and “would require policy decisions regarding changes to subsidy and farm support”.

Failure – or failure of ambition?

So despite the Rothamsted researchers finding, in 65% of the cases (involving 114 onsite tests) increases in soil carbon at or above the target level, 4p1000 is “unrealistic”. As the paper itself states, one of the four main problems is that “the necessary change of management would be uneconomic to the farmer under current conditions or impractical for some other reason. To implement such changes would probably require changes in government policies, regulations or subsidies to promote the practice.”

There are a number of issues with this. In a context of an ongoing CAP reform process, and it’s supposed purpose of providing public good for public money, the simpleton in me thinks that there is an opportunity to bring in these kinds of measures. Indeed these are the kinds of measures in the original CAP plans of the previous Commissioner in 2010.

For example, greening is a compulsory component of Pillar one of the CAP, supposed to make a contribution to agri-food’s environmental and climate change performance. Originally, it was intended to include not just crop diversification – a fairly meaningless term – but actual crop rotations. With the CAP greening failing so badly in delivering environmental and climate change improvements, as the European Court of Auditors clearly laid out in December, the case for a more robust agri-food policy with real delivery of deep greening is clear. Greening has led to change only on 5% of farmland, and is basically, despite the name and the rhetoric, still simply income support.

We need a CAP that becomes a Marshall Plan for bettering agriculture and food, not a band aid for business as usual.

There are some signs that the UK may be moving towards environmental performance in agri-supports, and away from direct payments. The new delivery vehicle offers some hope, however tentative, that this may happen with CAP too. (Alan Matthews compares both in his most recent blog post). Indeed, moving away from direct payments was also the main recommendation of the European Parliament’s Ag committee’s Dorfmann report, as we revealed last week.

In a context of tighter post Brexit finances, bigger challenges on the horizon, and such a verifiable poor performance of farming and food in environmental and climate change terms, is it really so ambitious to expect farmers to adjust their agronomic practices to justify the public money they receive?

Digging Deeper

Emerging grazing techniques, such as adaptive multi paddock grazing, has been shown in studies, including this 2018 publication in Agricultural Systems to be beneficial in terms of carbon and climate change mitigation in a number of ways. Not only can adaptive multi-paddock grazing “sequester large amounts of soil C” (Carbon), the emissions “from the grazing system were offset completely by soil C sequestration” according to the study. Thus, “soil C sequestration from well-managed grazing may help to mitigate climate change.”

And increasingly, the positive role of soil microbes for carbon sequestration in grassland systems has been noted by researchers , including a team published in Geoderma in 2017. “SOC soil organic carbon gains were essentially due to increases in POM-C (particle organic matter carbon) and MBC (microbial biomass carbon), accounting for 50.04 and 15.64% of SOC sequestration at 0–30 cm, respectively.” And this carbon could be built in under 80 years, the researchers claimed.

But its not just about what’s on top, it may be about what’s deeper down too. Published work in Nature Scientific Reports in 2017 revealed soils with high clay content in deeper layers lock away carbon for much longer, and at much greater depth than previously known.

While topsoil carbon is quite volatile, at deeper layers, carbon can be stored for longer. This is especially the case for “grassland soils with high clay content in deep layers, where the clay particles have washed from the topsoil to the subsoil.”

The researchers claim that the Paris Agreement of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) “has thus far only considered the top 30 cms of soil, known as topsoil.”

While this is indeed where most of the carbon is, as Dr Gemma Torres, lead author, explained: “most of the carbon in the topsoil is bound to the larger soil particles. These provide a tasty meal to soil organisms, which quickly release the carbon back into the atmosphere. This means that most of the carbon in the topsoil is locked away for less than 10 years”.

And this could have policy implications too. Speaking in 2017, Rogier Schulte said that “the new proposals by the European Commission for an Energy and Climate Framework for 2030 allows for a degree of flexibility in using soils to offset some of the agricultural emissions. After all, locking away carbon into the soil is one of the more cost-effective ways in which agriculture can contribute to reducing greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Our research shows that grassland soils with high clay content in deeper layers have even more potential than previously thought and can play an important role in the plans of EU Member States to meet their climate obligations; this opens up opportunities to incentivise climate-smart land management, customised for contrasting soils.”

The Stakes (for steaks) are High

All of this of course throws up as many questions as answers. Does this deep carbon let conventional grazing farming practices, and all that goes with them, off the hook? What about livestock farming’s other impacts – including its production of other other greenhouse gases such as Nitrous Oxide and Methane? There are arguments on both sides for this both these gases. Will EU Member States just take this as an opportunity to reduce their already meager climate change activities? Why not just rewild this land, and introduce nature based economies, as George Monbiot and others have argued?

Most pertinently, how does this, to use one of the terms that describes it, regenerative agriculture research, square with the high profile Grazed and Confused report, led by Dr Tara Garnett of the Food Climate Research Network? This report considered 300 studies and found extensive grazing at best can remove between 20% and 60% of the greenhouse gas emissions it produces. Much can – and should be said about this study, which, among other things, emphasises other regenerative practices not involving livestock, and also points to the paucity of animal protein produced from extensive grassland compared to other sources.

These are the questions to which we turn next, in considering where now for 4p1000.

Of course, sustainable farming is not just about climate change. Indeed, “one could argue that it is precisely this ‘single issue’ approach to investigating problems and solutions that has got us into the mess we’re in in the first place”. And who better than Tara Garnett of FCRN to say this?