Lire cet article en français

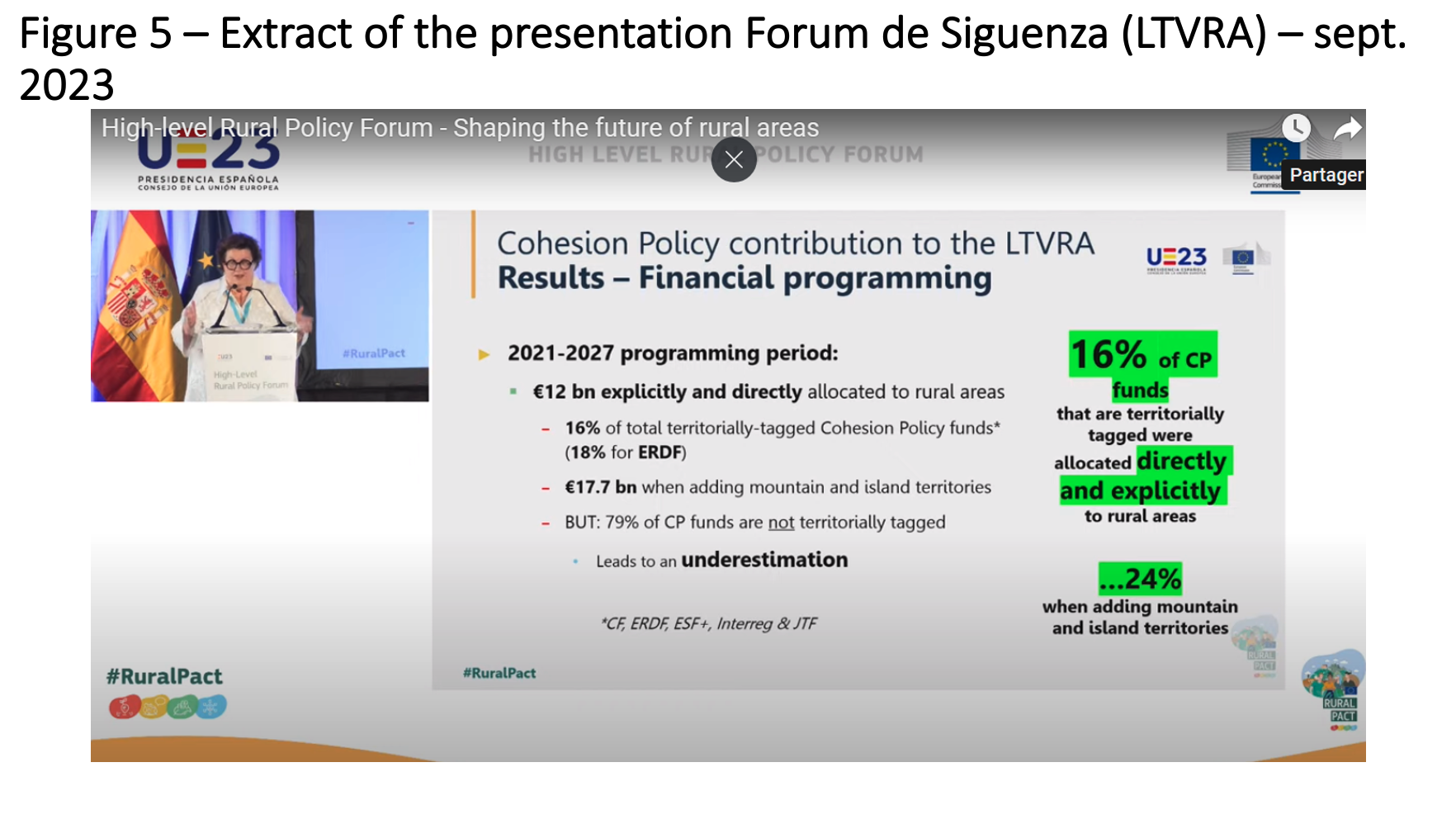

On September 28, 2023, a “High-Level” Forum on the LTVRA (Long Term Vision for Rural Areas) was held in Siguënza, Spain, aptly titled “Shaping the future of rural areas”. Part of the forum caught our attention: a plan to take “stock of existing support and looking forward”. This segment specifically addressed funding programs like LEADER or Cohesion Funds to support the implementation of the LTVRA.

In a preparatory document there was no mention of national parks or regional nature parks. At a time when climate change should shape the agenda in all levels of agricultural and rural public policies, it seems relevant to build upon what already exists in the territories – including natural reserves and parks, a concept shared by several member states.

In this article, exploring regional nature parks is a way to continue a cross-analysis of the trajectories of France and Germany, towards the construction of more resilient rural territories. Two economic sectors – eco-tourism and sustainable agriculture – are attempting to develop in these areas, leading to conflicting priorities. The essential fuel for these rural policies, the LEADER funds, has experienced specific setbacks in France, which should be mentioned to encourage vigilance in other member states.

An analysis by Marie-Lise Breure Montagne

A rural project territory shared by several European countries: the German NaturPark / the French “Parc Naturel Régional” (PNR)

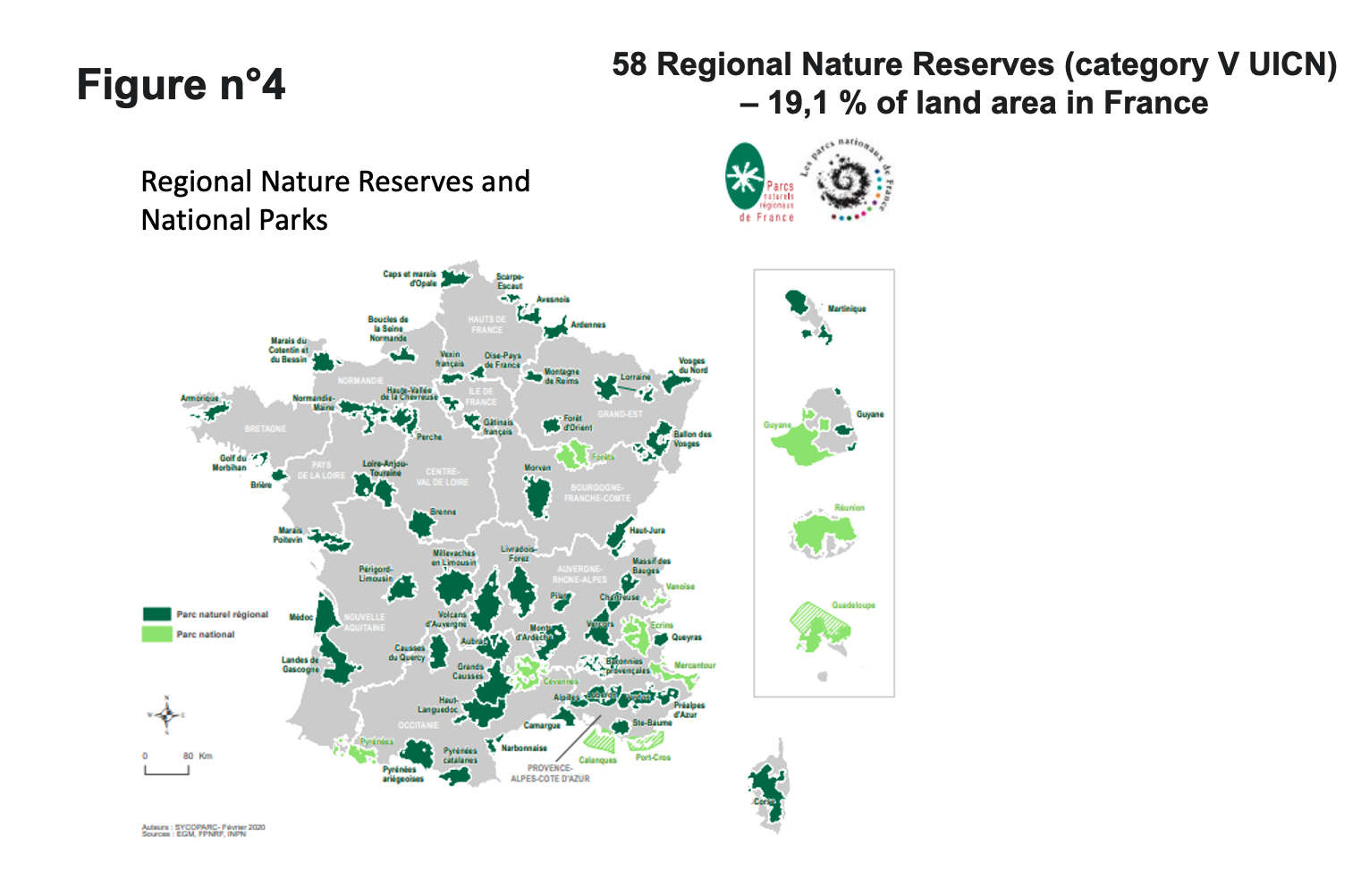

Despite “ecological planning” being frequently cited in French news, there is very little reference to the Parcs Naturels Régionaux. Parcs Naturels Régionaux (Regional Nature Parks) are guided by a charter with a strategic horizon of 15 years. Beginning with the Voynet law of 1999, the charters of PNR became in principle sustainable territory projects, adopted by a rural community to sustain and preserve an exceptional territory.

“Creating the Parc [Naturel Régional] is not an obligation for a municipality but a strategic choice, validated by each municipal council in the study area,” explains the PNR of Livradois Forez.

How does it work in France? Governed by the Environmental Code, the procedure for creating a PNR falls under the competence of the Regional Council (equivalent to the German Länder). The State accompanies and validates the steps by issuing an opinion. The partner communities are closely involved throughout the process.

In Germany, “nature parks” (Naturparke) are created on an associative initiative and they are largely financed and collectively managed by the Länder, administrative districts, and municipalities.

A major difference from French PNRs is that “only a minority of regional nature protection laws provide for a planning obligation. Normally, planning through a development plan or a land use concept is voluntary and only indicative in nature. Despite the gaps in regional legislation, 80% of nature parks have a plan.”

According to C. Giraud in Pour magazine (2022/2), German authorities are therefore responsible for the rules and mechanisms of environmental preservation, while recreational developments are mainly funded by private sources or public-private partnerships. Thus, what a nature park should be is defined in Article 27 of the Federal Nature Conservation Act. In addition, there is a national framework: the Quality of Nature Parks initiative, supported by the Federal Ministry for the Environment, and the guidelines Nature Parks in Germany 2030 – Tasks and Objectives provide the framework for the continuous qualitative development of nature parks. The Wartburg Program summarizes the strategic objectives of nature parks by 2030 and ten framework conditions necessary for policymakers. These provisions are valuable in making these territories eligible for national or European funding.

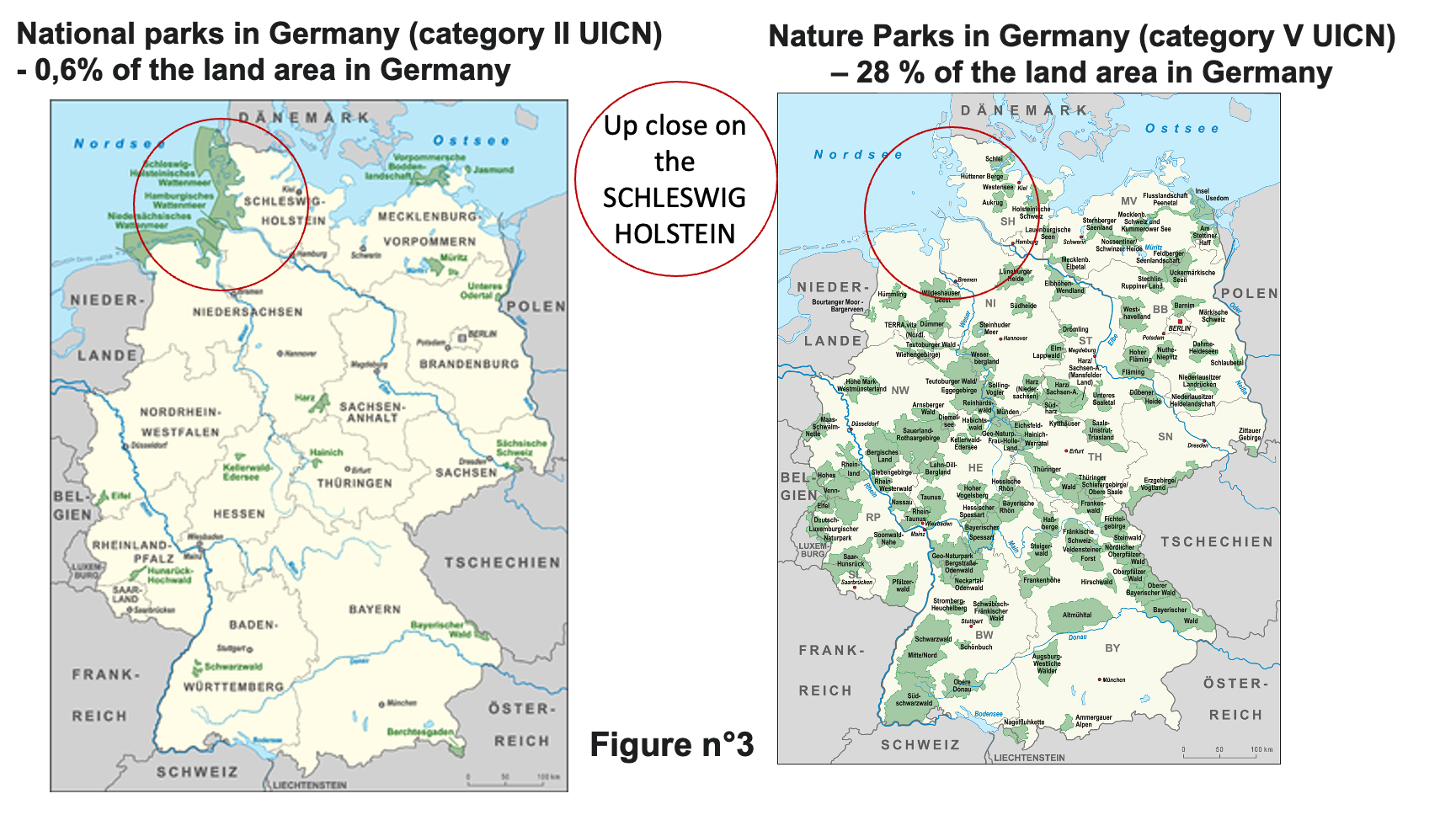

In Germany, there are over a hundred “Naturparks” (105), covering nearly a third of the national territory (28%). Their mission is “to preserve, maintain, develop, or restore landscapes that are of exceptional importance for ecological or aesthetic reasons”; “they combine biodiversity conservation and the development of rural regions [including agriculture], they offer attractive recreational opportunities, promote public health, support sustainable tourism, and education for sustainable development.”

These missions make them quite comparable to French PNRs, which were actually heavily inspired by the German model during their creation.

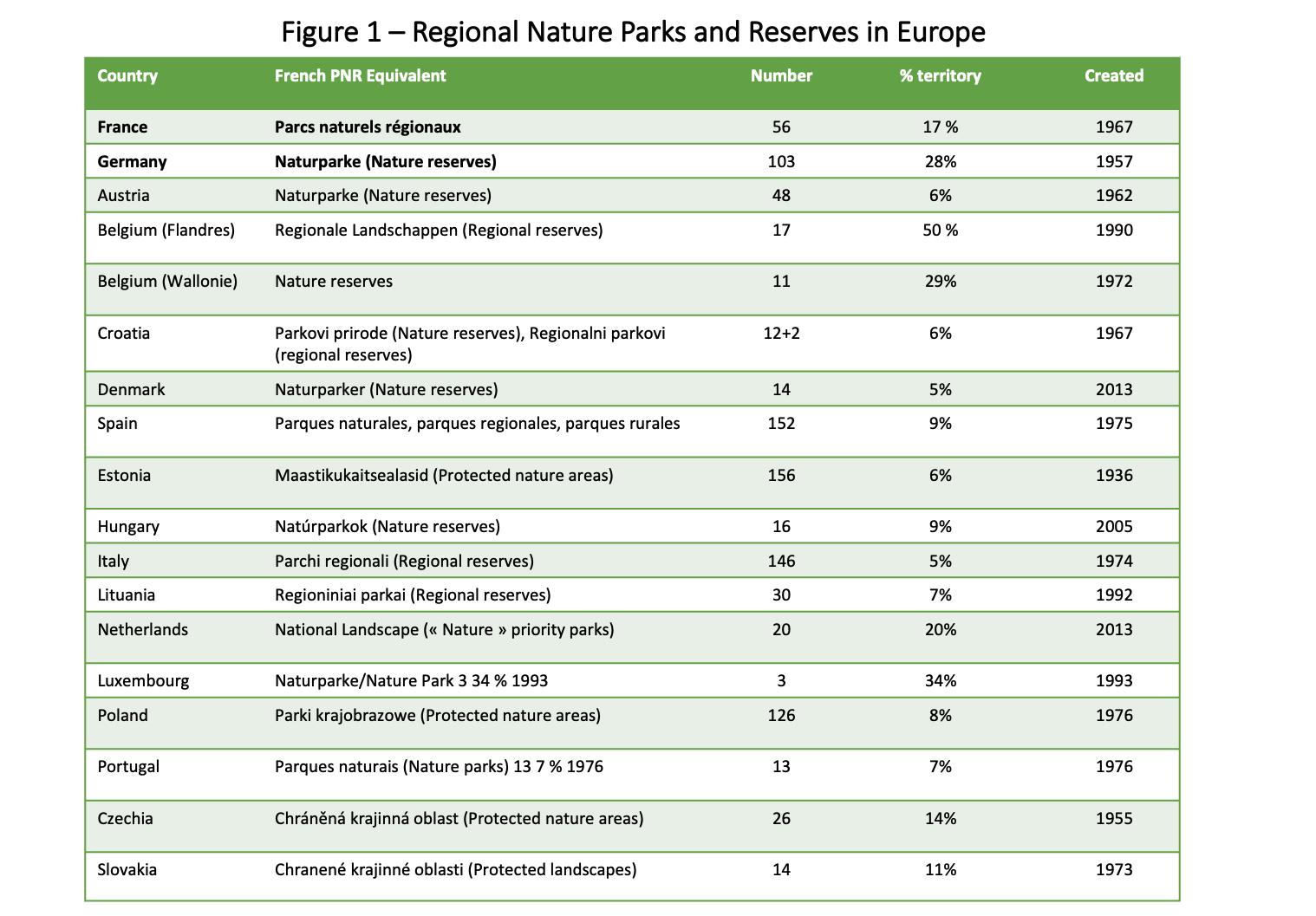

The European Federation of Nature Parks (Fédération Europarc) has compiled a report on “regional and landscape nature parks in Europe” (Köster, Denkinger, 2017). This provides a synthesis of European initiatives similar to the German Naturparke (Europarc being an associative initiative of German origin) (Figure 1).

The European Federation Europarc considers that the “regional and landscape natural parks of Europe” include more or less all the areas that fall under the IUCN category V (inhabited protected areas – International Union for Conservation of Nature); thus the equivalents to German Naturparke or French Regional Natural Parks, throughout the EU, are numerous. Giraud in Pour magazine (2022/2) says these parks are therefore more of public policies aimed at supporting rural or peri-urban areas than strictly protected areas.

European territories that do not have these regional parks are either small islands (for which the regional level does not make sense: Malta, Cyprus) or countries well known for their strong centralization, like Greece or Sweden.

In concrete terms, these project areas (“territoires de projet”) embody bottom-up approaches (the mantra of the LTVRA community): “Following the example of the French PNRs, which are used as “Swiss Army knives” for sustainable rural development (Milian 2020) and whose leitmotiv is to “convince without constraining”, the various “nature parks” that exist in Europe embody the national variations of the same principles of contractualisation, collaboration and participation, which today enable the various players to think about and administer the sparsest areas” (GIRAUD, 2022).

The Regional Natural Park, a melting pot for opening up public policies in silos?

Example of agriculture and tourism, the two pillars of local rural development.

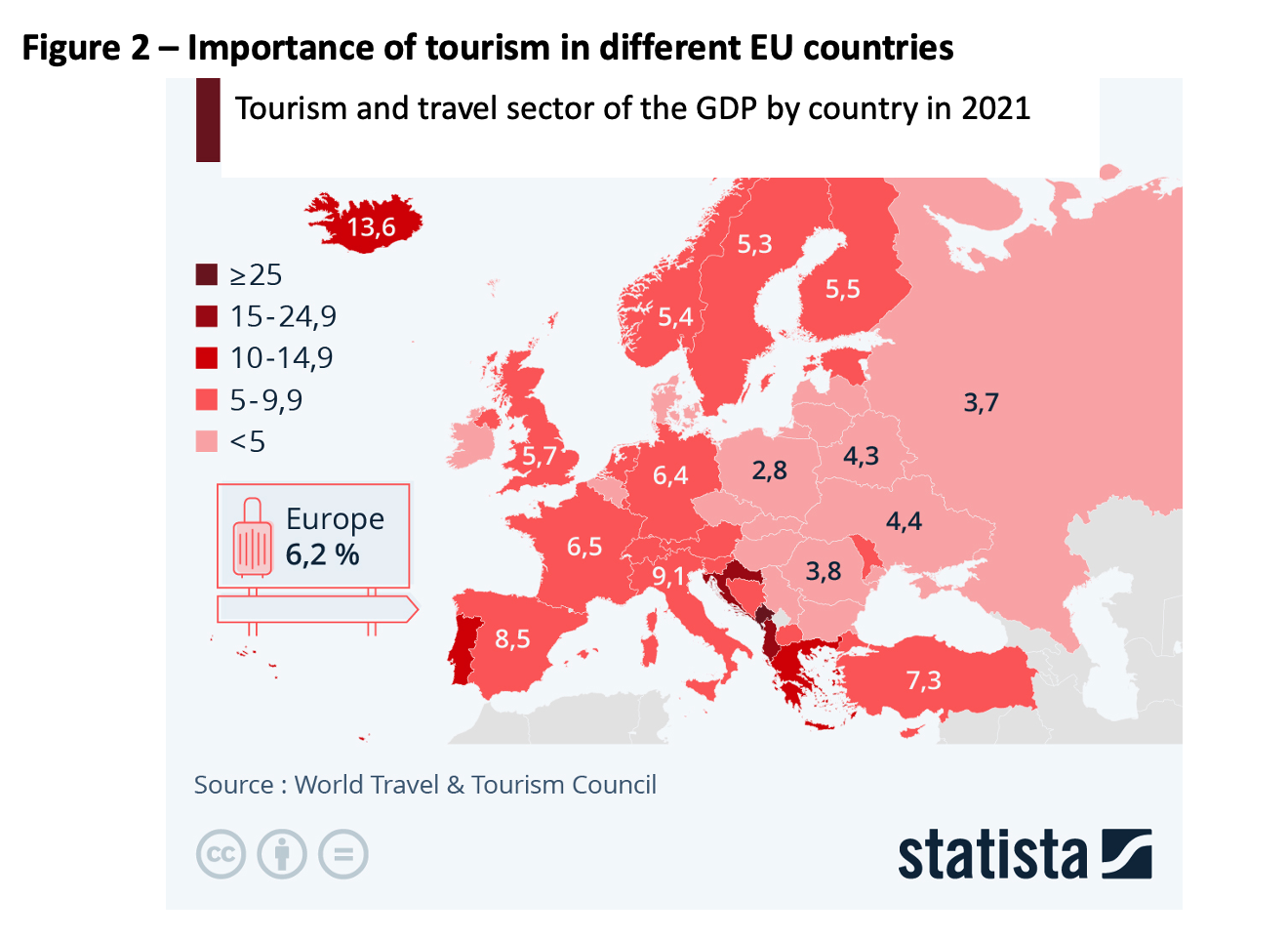

Two economic sectors characterize a large part of rural regions in France: agriculture and tourism. The map below (Figure 2), while encompassing mass tourism in European cities and more confidential forms of eco-tourism in rural areas, shows an interesting zoning: tourists’ inclination towards Southern Europe; pronounced disaffection for the East.

France and Germany are comparable in terms of tourism: France’s tourism GDP: 6.5% / Germany’s tourism GDP: 6.4%, figures close to the European average: 6.2%. Many observers of this sector expect to see significant changes: regions of tourist frequentation could be disrupted by extreme summers. Furthermore, mass international tourism could leave even more space for domestic tourism, creating more added value for territories and their economic fabric.

The words used to describe the “Path to the Future of Rural Areas by 2040” (LTVRA) do not mention the heavy trends of mass tourism diversion in response to climate change: “[The Parliament] knows that tourism can represent an important source of income for rural communities, and highlights the potential offered by diversified models of sustainable tourism […]; requests efforts to be made to strengthen rural tourism, such as wine tourism, in strategies for diversifying the rural economy, alongside the agricultural and food sectors.” Wine tourism is consensual because it caters to both markets: tourist buses in the cellars of Champagne or Bordeaux, or hikers who make a stop at a family-owned farm with small vineyards practicing organic agriculture.

In French regional nature parks, as indicated by their national federation, wine is not the only product that tourists may encounter: a strong representation of grassland and pastoral areas (60% of the UAA) compared to the national average (40%) characterizes them.

Some quick figures:

- 94% of the municipalities in the Parks are located within a protected designation of origin or controlled designation of origin.

- 20% of agricultural product sales are through short circuits (15% at the national level) mainly through direct sales at farms, sales at markets, and to retailers.

- 7% of agricultural land is dedicated to organic farming (4% at the national level) (figures that are already outdated, nearly 10 years old).

In Germany, “the nature park is a category of protection that combines concerns for nature conservation and sustainable use, especially agriculture, forestry, and tourism. Cultural heritage only plays a role in relation to landscapes. A peculiarity of German law is that the nature park must mainly consist of landscape protection areas and/or nature reserves.”

It should be noted that four German regions (out of 16) – Bavaria, Lower Saxony, Hesse, and Schleswig-Holstein – have used their constitutional power to deviate from federal legislation regarding nature parks. Thus: “Schleswig-Holstein, in northern Germany, limits the objectives of the nature park to a single objective, namely recreation, including tourism. The three other exemptions [from the other three states] are less significant and concern the definition of the minimum area of the nature park.” It should be emphasized that Schleswig-Holstein is one of the few states to have both types of parks on its territory: national parks (Figure 3 on the left) and NaturParks (Figure 3 on the right). National parks are intended to allow wildlife and plants to live without human disturbance, but also to give visitors the opportunity to be close to nature; human activities are subject to different restrictions in different parts of the German national parks. Therefore, it made sense for the state to specialize both types of parks for their tourist vocation.

The potential conflicts of interest between tourism and agriculture are making headlines in France, one being water use conflicts – a key natural resource shared by both activities, often with the same peak usage in summer. The LTVRA has not failed to mention fishing as a driver of rural tourism: “recreational fishing and … angling, which are likely to attract tourists throughout the year” … without mentioning the increasingly alarming number of rivers drying up in summer and even autumn. “A tourist consumes 60% more drinking water than a permanent resident of the area,” according to Les prionniers de sécheresse, a tv program by Francetv in 2023.

The grand cycle of water connects the agricultural sector and tourism. The Marais Poitevin Regional Natural Park is the only park that has lost its status as a Regional Natural Park (PNR), obtained in 1979, and lost in 1997. In 2009, the CNPN (National Council for Nature Protection) again issued a negative opinion on a new PNR labeling by the Ministry of Ecology (during the renewal of the Charter, every 15 years), due to the disappearance of wet meadows in favor of intensive cereal farming. Out of the original 65,000 hectares of wet meadows, only 25,000 hectares remained in 1990.

It would take until the following decade to have a vote from the CNPN, in favor of the proposal presented by the park. The new charter covers the period 2014-2026, or the equivalent of two LEADER programming periods. The territory has kept the memory of this long struggle and is now moving on to a new one: thus, the leader of the collective “Bassines, non merci,” co-organizer of the water convoy with the Confédération Paysanne in August 2023, lives in and promotes this territory.

Other parks have learned their lesson as well, such as the Livradois Forez Regional Natural Park. During the revision of the PNR Charter (2026-2041), when asked “what must be done by 2041?”, the mayor of Dorat (VP of the ‘Thiers Dore et Montagne’ intermunicipal authority) responded without hesitation: “All subjects are important and interconnected. But the water issue must be the priority of the Charter… In my opinion, the most important thing is to prioritize the ‘natural environment’ issue over the drinking water issue… because when the grand cycle of water is disrupted, the small cycle [Drinking Water Sanitation] will be even more disrupted.” These statements are even more interesting considering that the Massif Central has long been called the “water tower of France,” and that the availability of the resource is not as critical as in other areas.

The financing of regional natural parks by European funds: rise and fall?

The draft paper for Siguënza LTVRA Forum provides an overview of financing possibilities for projects in rural areas:

“The European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and Cohesion Policy (ERDF, ESF) are the basic sources of EU financing for rural change, but several other funds (Resilience and recovery funds) or programs (e.g. ERASMUS, LIFE, etc.) can also play a role. These funding streams can also be combined through multi-fund approaches to create even more opportunities for action on the ground.”

The most crucial information during the Forum: “Cohesion fund [policy] was validated before the LTVRA“; and also: “79% not yet territorially tagged“… “our member states have not stated on which kind of territories these funds will be tagged” (figure n°5). Regions will have to imagine a coherence that has not been designed “from above” – or more likely, bypass the LTVRA which also ignores some of their most structuring and rooted achievements.

For the other major source of funding, the preparatory document for the forum addresses the accessibility of European funds for rural actors: “Animation, advice and help meeting the funding requirements is an essential element of community support by many LEADER LAGs“.

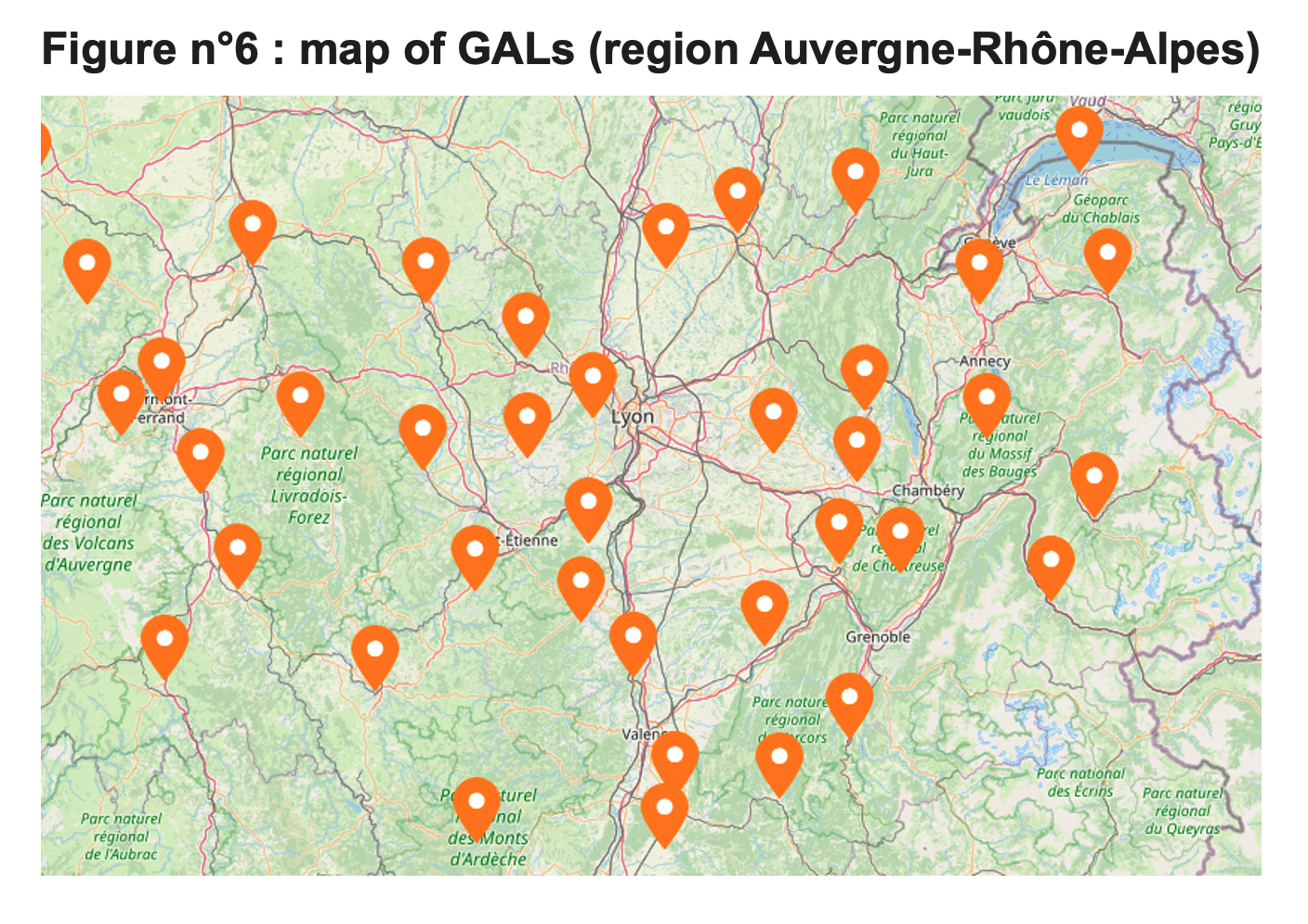

Regarding the subject at hand: the PNRs, it should be noted that their geographical scope is also that of LEADER LAGs (Local Action Groups), in a number of cases. For the French Auvergne Rhône-Alpes region, during the previous programming period, the implementing structure of a LEADER LAG was the PNR (see figure n°6): both for the PNR of the Volcans d’Auvergne, the Livradois Forez PNR, the Massif des Bauges PNR, the Chartreuse PNR, and the Monts d’Ardèche PNR (representing rural territories with a total of 540,000 inhabitants).

This long and patient work of creating and managing a PNR is now being questioned:

“As the regions begin the selection procedure for the local action groups (LAGs) responsible for implementing the European local development program LEADER, caution remains necessary. Especially after a particularly tumultuous 2014-2022 programming period [many technical difficulties: software, etc. related to the change in responsibilities of the regions, becoming managing authorities for LEADER funds while also undergoing a change in scope: NOTRe law]. The temptation of certain regions, such as Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, to pool LAGs at the departmental level raises concerns about a deviation from the very philosophy of this program, which is based above all on proximity.” (source : january 2022).

Over a year and a half after this alert from the Banque des Territoires: France has not yet called this region to order, even though there are grounds for several violations of laws, regulations, and structuring principles of the Republic.

For example, the Livradois-Forez Park (photo n°7) was one of the few European territories to experiment with the LEADER program as early as 1991.

The principle is to support projects in the territory that meet its needs. Clearly, the scope of the project territory (which is the PNR) is one of those needs. These fundamental principles of the LEADER program have not changed since 1991. The ongoing program for the period 2014-2022 has supported approximately 270 operations for a total amount of nearly 8 million euros in European LEADER funding. These operations are spread across the territory of the four eligible intermunicipal communities.

The new organization initiated by the region is disrupting this park, just as it is beginning to revise its Charter: “The Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes Region, which manages the EAFRD program for the period 2023-2027, launched a call for applications at the end of March 2022 for rural territories to develop their application for the next LEADER program by December 30. The credits planned at the regional level for this program are significantly lower than in the previous period, so the Region has decided to limit the number of applications to twelve, which must be at the departmental level. The Livradois-Forez Park has therefore joined forces with the five other rural territories in Puy-de-Dôme to develop an application with the support of a consulting firm.”

The erasure of “bottom-up” initiatives, patiently built by rural communities, is therefore taking place. This is not in keeping with the good intentions of the LTVRA.

Conclusion

All the PNRs currently revising their charters have the same time horizon as the LTVRA (i.e., 2040); this is also the case for all the new PNRs being created or under study.

In order to allow for nuances or openness to any form of future territorial innovations, the LTVRA and its related work do not explicitly mention the rural project territories that are the regional nature parks (or their German equivalent: naturparks). This overlooks a unifying concept among many European countries, at a time when the climate emergency is pressing on our minds. And with the certainty that territories will be left to their own devices or, at best, to their own capacity to develop relevant approaches in proximity.

Since the LTVRA’s primary intention is to “break down policy silos,” a mantra for driving ecological and social transition, it is useful to observe the coexistence of the two major economic sectors in rural areas: agriculture and tourism. And this brings us to the cross-cutting issue of the water cycle. However, adaptation to climate change is not a priority for the LTVRA either, as it still adheres to an old and traditional vision of “prosperous territories,” where natural resources are simply an adjustment variable. To be followed during the debates for the upcoming European elections – and beyond!

In 2023-2024, the Rural Resilience project embarks on a new phase of joining the policy dots while continuing to nurture what we have built together, and widening the lens from France to Germany and the broader Europe. To learn more, visit the project page, and follow ARC2020 on LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook or Instagram.

Read More:

Water as a Common Good .. and climate risks, a common destiny – Part 2/2

Access to Land: More Resilient Agriculture – Without Any EU Legislation? (Part 2)

Access to Land: Looking to Europe to Secure Local Farmland? Part 1

Beyond the Harvest: Health Effects of Pesticides on French Farmers

France | Democratising Food Policy – Tweaking The Financial Toolbox

Ernährungsrat: The democratic potential of Food Policy Councils in Germany