Lire cet article en français

In the age of water scarcity, drought risk management in agriculture is leading to a boom in mega-basins in France, as has happened to disastrous effect in Spain. French researchers have dubbed this phenomenon “insurance through irrigation”. In part 1 we took a closer look at crop insurance, a protection available since 2005 and supported by CAP funding. Indeed the mega-basin issue exposes French agriculture’s startlingly low rate of insurance coverage for climate risks: only 17% of UAA [illustration 1]. In Germany, the rate of coverage is three times higher (>60%). Marie-Lise Breure-Montagne reports.

To go a step further, in this second part we look at the resilience of agricultural insurance systems, a function fulfilled by public (France, Spain) or private (Germany) reinsurance. Or ultimately, by national solidarity. Europe witnesses these disparities between countries, while the ongoing climate crisis is becoming more acute every year.

Source: French Ministry for Agriculture and Food Sovereignty, via Twitter, April 2023

Systemic climate change: a growing role for reinsurance?

For agriculture and climate analysts, it’s been one nightmare year after another: extreme drought in 2003 and 2011, excess water in 2016, and other extreme weather events.

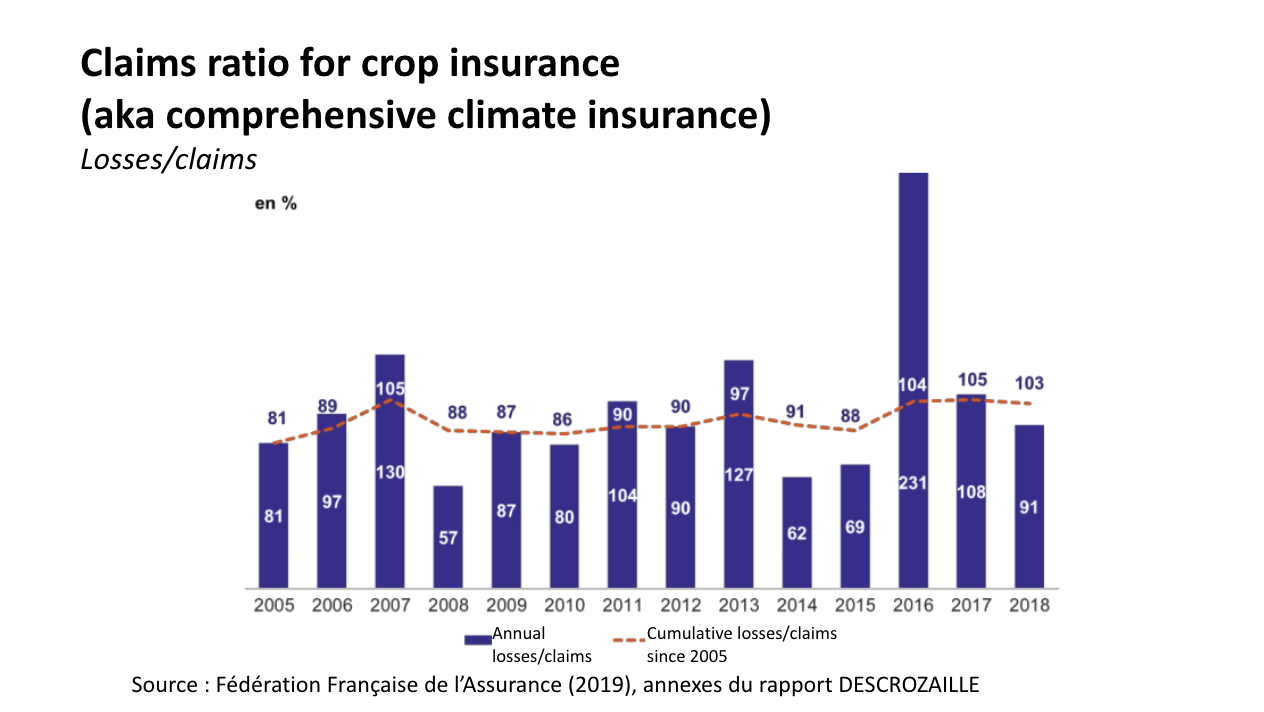

“[Implemented in 2005], over 14 years of operation, crop insurance [aka comprehensive climate insurance (multi-risques climatiques, MRC)] has yielded a benefit only three times: in 2008, 2014 and 2015” (Figure 3).

An insurer can make a loss. This is because, in addition to the cost of claims, the insurer has to cover the costs of new policy sales, claims management and payment, expert appraisal fees and, where applicable, reinsurance costs. Insurers have the same need for a safety net as their customers, the farmers. This is called reinsurance.

This little known concept is defined as follows:

“‘Reinsurer’ means an undertaking which is authorised or licensed to take up or engage in the business of reinsurance activities” “Reinsurer: a company that provides financial protection for insurance companies”.

Reinsurance companies, whether public or private, are situated at the end of the agricultural risk management chain. The next and ultimate link in this chain is national solidarity, which means the damages suffered are covered by the State (in other words, taxpayers).

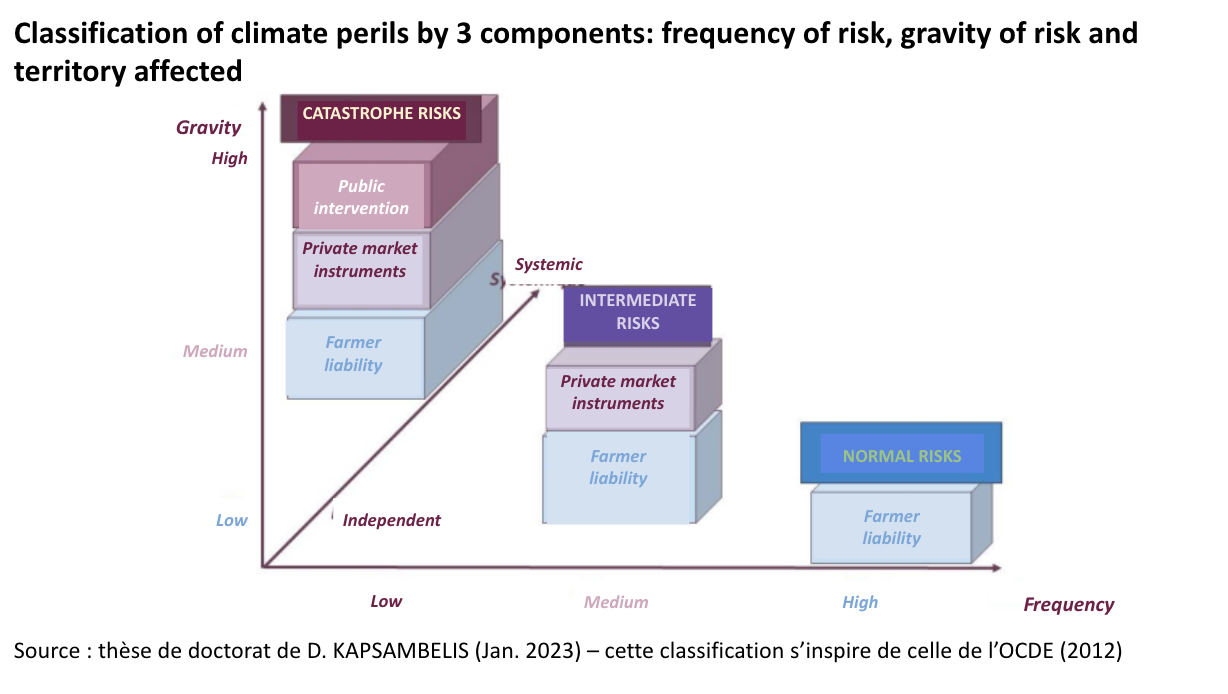

Drawing on an OECD risk typology (figure 4), Dorothée Kapsambelis explains that normal risks are the responsibility of the farmer, while intermediate risks can be covered by market instruments such as insurance, noting that “the insurer may have recourse to a reinsurer to bear the risk. In this case, mutualisation operates on a broader, usually international, scale” (D. Kapsambelis, PhD thesis 2023). Extreme risks are covered by national solidarity, she concludes. Which are precisely the climatic risks that lie ahead, according to the IPCC. Kapsambelis’ work uses climate data from the IPCC’s RCP 8.5 scenario (the most likely, given inertia) to build a model of future damages.

This thesis is valuable because it is co-supervised by the University of Bretagne Loire and Caisse Centrale de Réassurance (CCR, a public-sector reinsurer ; CCR does not manage the reinsurance of agricultural risks, at least until now, except for damage to farm buildings).

The research aims to “inform national thinking on the evolution of risk management policies in agriculture in France to cope with climate change”. Kapsambelis focuses on climate extremes that are limiting the effects of species resistance, for two major agricultural production systems in France: straw cereals and grasslands. “This thesis aims to model the impact of climate change on extreme climatic events and their consequences on agricultural productions at the French farm scale. This research will question the role of crop insurance and its sustainability in a close future, 2050. […] the methodology combines climatic projections from ARPEGE-Climat and farm structure vulnerability paths.”

The results of the model, developed in partnership with Météo France, speak for themselves: drought is more to be feared than excess water: “This analysis shows that the risk of excess water does not change by 2050 in terms of frequency and intensity across mainland France. An excess of water such as that experienced in 2016 has a return period of 50 years in current and future climates. However, historically, these events have resulted in the greatest crop losses ever recorded for soft winter wheat and winter barley […] (almost double the losses caused by drought). […] the risk of extreme excess water has risen by 30% in the northern half of France, in particularly productive regions. However, this trend remains much lower than that observed for the risk of extreme drought” (D. Kapsambelis, PhD thesis 2023).

The outlook for drought, illuminated by the mathematical model, leaves little room for optimism: “Analysis of events combining both extreme drought and extreme excess water reveals that their frequency doubles by 2050. In the future, these events will more often than not involve extreme drought in southern France and excess water in eastern France and along the Atlantic coast. These events will increase in intensity by 2050.” In addition, the duration of drought increases: “In the 2000 climate, droughts lasted 37 days on average, whereas they will last 43 days on average in the future climate. These results are in line with the increase in drought duration observed by several researchers” (D. Kapsambelis, PhD thesis 2023).

This leads Kapsambelis to the following conclusion: “Costing of the scenarios will allow us to assess the financial integrity of public and private systems (insurability) in the face of the increase in climate risks expected over the coming decades”.

One of her thesis supervisors, economist Jean Cordier, spoke out during the Varenne de l’Eau consultation on responses to the effects of climate change: “When I read that the State will only put €600 million a year into reinsuring agriculture, I can tell you that this is far from enough. I’ve worked on this for years. Twice that is needed: €1.3 billion euros a year.”

If the financial integrity of the insurance system is fragile today, due to underestimated needs, where will it be in 2030, 2040 and 2050?

Reinsurance – a public or private model?

The French reinsurance model for agriculture is still under debate. The outlook is indicated by last year’s decree (Ordonnance no. 2022-1075 following the law of March 22, 2022). France has used benchmarking against other major European countries to inform its thinking.

It’s not easy to compare the French and German systems. After all, two of the world’s three largest private reinsurers are German: Munich Re And Hannover Re. Modern reinsurance was invented in Germany, thanks to the opportunity created by the development of industrial sites which were difficult to insure.

Germany’s strength is its longstanding history of reinsuring agricultural risk – since 1919, in the case of Munich Re. Its messaging fully acknowledges the risks of climate change:

“Wherever you are in the world, we can assist you in factoring in the possible impacts of climate change, such as increasing rainfall, heatwaves, droughts, unseasonable frosts, and windstorms. These conditions present serious challenges to your business as an insurer of agricultural risks.”

In 2015, under the G7 presidency, Germany, together with its world-leading reinsurers, launched the InsuResilience initiative in Bavaria. Two years later, under Germany’s G20 presidency, it expanded to become the InsuResilience Global Partnership. By 2025, 500 million people (in all sectors) in the poorest countries should have access to insurance against climate risks.

However, in Germany a purely private model is not the norm: livestock farmers pay compulsory “contributions” (Beitragsplicht) to the Länders (not to insurers) so that they can be compensated in the event of illness in their herds. Furthermore, “the Federal State, for its part, assumes crisis management”, meaning that it is the last resort if the insurance system is overwhelmed by the scale of the damage. “The federal government can also participate in the granting of subsidies to cope with damage in agriculture and forestry caused by natural disasters or adverse weather conditions, by concluding administrative agreements with the Länders”. (Coverage of risks in agriculture and agricultural insurance – French Senate report 2016).

What is the logic of combining private reinsurance with national solidarity? Researchers at INRAE (2006) explain how drought, more than other climate risks, risks undermining the insurance system:

“[The risk of drought] has the specificity of being (unlike hail, for example) a ‘systemic’ or ‘correlated’ risk (the probability of the event occurring is [relatively] low, but when it does, the losses are considerable and affect a large number of policyholders simultaneously). A second problem stems from the difficulty of attributing to drought alone losses that may also result from inappropriate crop management or choice of enterprise. The systemic nature of the risk poses the problem of reinsurance, which may be provided by private companies or the State, depending on the country. The examples of Spain and the United States, where the State acts as reinsurer, confirm the cost to the community of systems that cannot achieve financial integrity solely on the basis of premiums paid, and are heavily subsidised by the State, either directly or through reinsurance. The possible intervention of the State as reinsurer then depends on the development of the private reinsurance market [Spain is not Germany] and the existence or non-existence of public compensation systems (as in France)” (INRAE, 2006, at the historic moment of the introduction of crop insurance policies called “MRC”).

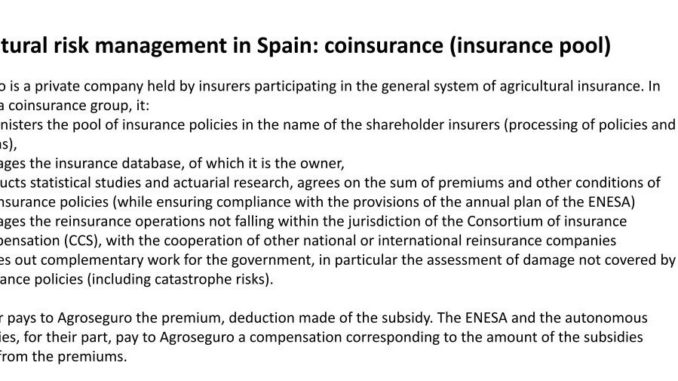

Taking inspiration from the Spanish approach over the past 40 years, the French government has proposed a co-reinsurance pool to ensure the continued availability of insurance. Continued up to a point, of course, since droughts are increasingly less rare. And Spanish ‘insurance through irrigation ’, which is part of this system, is far from sustainable.

“The Spanish co-insurance pool Agroseguro inspires one of the three scenarios for pools envisaged in the [French] government’s bill. Agroseguro asserts that its model is fully compliant with European law, and that it has enabled insurers to achieve a very high level of solvency”. Critics of the French pool proposal point out that Agroseguro was set up in 1978, before Spain joined the European Union and was subject to European competition law.

One significant difference between Spain and France is the number of private agricultural insurers: 21 in Spain, compared with nine in France (mainly Groupama and Pacifica). The Spanish example of ‘public-private’ reinsurance has been hailed at various stages, starting with the pool advocated by parliamentary deputy Frédéric Descrozaille:

“The third [axis of reform in the law passed in March 2022] is that of State intervention for the management of ‘strong’ risks: exceptional or systemic, i.e. uninsurable or necessitating public reinsurance in the case of phenomena of exceptional scale…the presence of Caisse Centrale de Réassurance within the pool, as a trusted third party, would be likely to elicit crucial trust on the part of actors” (Descrozaille report for the French National Assembly).

France’s July 2022 decree on the development of climate risk management tools in agriculture endorses the proposal, mentioning it as a possibility, albeit in less precise terms:

“CCR may contribute to the development, implementation, monitoring and assessment of public policy on the management of climate risks in agriculture and the development of insurance against these risks,” thus amending the Insurance Code. “A grouping may be formed by insurance companies in order to carry out […] reinsurance activities for the benefit of its members,” states the decree. “Any insurance company that sells insurance products against climate risks in agriculture benefiting from the support provided for” to comply with CAP criteria (understand : the clients of the insurance companies in the pool must be eligible to CAP support as described in part 1). “The grouping may take out […] one or more policies with a reinsurance company to cover its risks” (Ordonnance no. 2022-1075 of July 29, 2022).

“Reinsurance companies or their representatives and CCR may participate in the governance or in the consultative and deliberative bodies of the grouping”. In effect, this is public-private governance.

What’s happening at European Union level?

At a time of tackling climate change with the Green Deal and related policies, it is legitimate to wonder exactly what action the European Union is taking with regard to this seemingly fragile insurance system. Unsurprisingly, it is approaching this issue from the angle of globalisation of the insurance sector, with an EU-US agreement.

In 2015, the EU’s harmonisation of insurance through the Solvency II Directive 2009/138/EC (see summary) paved the way for negotiations with the United States on insurance and reinsurance across all economic sectors. Negotiations were concluded in January 2017. The agreement came into force on April 4, 2018, although it had been provisionally applied since November 7, 2017.

Subsequently, the work of the European Council led to a proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a framework for the recovery and resolution of insurance and reinsurance undertakings. The legal grounds for this initiative is summarised as follows: “Currently, insurance recovery and resolution systems [for insolvencies] are national and only in place in a handful of Member States […] due to the effects of a failure of any [insurance or reinsurance] undertaking in the Union, it can be better achieved at Union level. Therefore, the Union may adopt measures, in accordance with the principle of subsidiarity as set out in Article 5 of the Treaty on European Union.” Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council

To sum up, the European Union is taking over this non-exclusive competence (at the end of the line of bad choices made by European agriculture: the failure of insurers), while, at the same time, the EU has just given the Member States a free hand with the renationalisation of the CAP.

Conclusion:

As INRAE pointed out back in 2006, in the face of more frequent, intense and longer-lasting extreme droughts, public action on water scarcity can take three directions:

– Resource increase (adjusting supply to demand): This approach produces the mega-basins described in part 1 of this analysis. One major drawback is that you have to believe in magic water and magic money – to keep expanding the basins.

– A posteriori compensation (via public or private insurance): As described in part 1. In part 2 we have examined the consequences of agricultural insurance: the need for public or private reinsurance, which does not rule out the risk of system failure. The only good news is that the EU and insurance system actors are aware of this: all are ill-equipped to navigate the changing situation around water scarcity. The Descrozaille report refers to “a number of questions that are part of a transitional phase to support change, and that need to be addressed as part of a governance structure involving the insurance and reinsurance professions, the agricultural sector and the State”.

– Water savings (adjusting demand to supply): To be explored in a future analysis (next year). Unlike reinsurance – and the globalised private reinsurance sector – water savings in agriculture will take different approaches that vary greatly from one territory to another.

The insurance system is not entirely disconnected from this third path: essentially, some insurers may decide to stop insuring certain production models.

In 2023-2024, the Rural Resilience project embarks on a new phase of joining the policy dots while continuing to nurture what we have built together, and widening the lens from France to Germany and the broader Europe. To learn more, visit the project page, and follow ARC2020 on LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook or Instagram.

Read More

Access to Land: More Resilient Agriculture – Without Any EU Legislation? (Part 2)

Access to Land: Looking to Europe to Secure Local Farmland? Part 1

Beyond the Harvest: Health Effects of Pesticides on French Farmers

France | Democratising Food Policy – Tweaking The Financial Toolbox

Ernährungsrat: The democratic potential of Food Policy Councils in Germany

1 Trackback / Pingback

Comments are closed.