Lire cet article en français

Blue gold: water is one of the most precious resources for agriculture and for life. In part one of this analysis, Marie-Lise Breure-Montagne looks at the difficult transition from acceptance of risk to transfer of climate risks (beginning with drought) to insurance companies – developments which spotlight inequalities in the circumstances of farmers across Europe.

Intro

“We have to prepare for the recurrence of droughts… [an agriculture in transition] is an agriculture that designs its system for water scarcity,” explained the French Minister of Agriculture earlier this year, before the clashes over the mega basin construction projects in Sainte Soline.

But why speak of scarcity when the water table can be tapped, outside periods of restrictions, to fill mega-basins the size of 15 Olympic swimming pools, where upwards of 20 to 40% is lost to evaporation?

It’s a short-sighted solution to reducing the risk of drought, as French hydrologist Emma Haziza sums up as follows: “Those who can afford to create a basin will privatise part of the water table, and it will lower for everyone, including small farmers with a small borehole in the vicinity.” Another major drawback: the depleted water table is disconnected from the river it supplies. In the short and medium term the river is unavailable for other uses, such as drinking water (surface water is the source of one-third of drinking water in France). The sole ‘rationale’ behind the use of mega-basins to minimize the risk of drought, according to Haziza, is that those privileged few with mega-basins can get around irrigation bans. (Note that these mega-basins are 70% subsidised with public funds.)

For the basin operators, the trick is to fill up on groundwater during the winter. A practice that is “unforgivable”, say opponents versed in the complexities of the water cycle.

It’s a shocking example of the monopolisation of water, our common good. Watergrabbing is accelerating the rate of aridification in regions that have adopted these predatory pseudo-solutions (Chile, California, Spain). In France, the summer of 2023 was marked by the Water Convoy: a week-long festival-like mobilisation of farmers from the Confédération Paysanne, activists from the “Bassines Non Merci!” Collectives, and other citizens, who marched from Poitiers surroundings to Paris. Their demand was simple: a moratorium on public funding for mega-basins. To turn off the tap of easy money, which is draining public funds into false solutions to the drought. And to mobilise beyond the circle of those most concerned. A moratorium also means giving more serious thought to the problem of adapting agriculture to climate change. This message was brought to the door of the Loire Bretagne Water Agency, where the convoy stopped for two days, before winding its way on to the French capital.

The current mega-basin boom can be explained as a form of “insurance by irrigation”, according to some researchers. Mega-basins accounted for 7.3% of agricultural land in 2020, compared with 5.8% in 2010 (source: France Nature Environnement). And this is only the beginning, given the numerous mega-basin development projects currently under review. Are there more collective solutions and, above all, more sustainable solutions to the major risks of drought and other climate disasters? How to resolve yet another French paradox, as France leads on climate change impacts, yet lags behind other Member States on crop insurance? What lessons can be learned from comparison with a large country like Germany on these sensitive and crucial questions?

According to the french economist Jean Cordier, farmers have to deal with four basic methods of risk management (climate and other risks):

- acceptance of the risk;

- transfer (via insurance);

- risk reduction on a case-by-case basis. Mega-basins are an extreme example of risk reduction (due to their medium-term consequences) and reserved for a privileged few;

- diversification, to minimise the overall impact of risks attached to one type of activity.

Part 1 of this analysis looks at the difficult transition from acceptance of risk to transfer of climate risks (beginning with drought) to insurance companies – developments which spotlight inequalities in the circumstances of farmers across Europe. Part 2 will examine resilience, and how French agriculture’s system of resilience – crop insurance – compares with different “solutions” in Spain and Germany. Insurance cannot function without reinsurance, which brings us back to the alternative of public versus private reinsurance. Another analysis (next year !) will explore more long-term levers: large-scale diversification (choice of varieties, crop rotation, and other innovative agroecological practices).

Inequalities between European countries

Agricultural climate risk management differs between European countries due to different climates; different degrees of intensification of farming systems, corresponding to different climate vulnerabilities; different possibilities for irrigation in the event of drought; different impact of climate change; different institutional denial of the scale of climate change (as evidenced by the basins in France, which the french Minister M. FESNEAU charmingly refers to as “replacement reserves”).

Farmers’ perceptions of risk have an impact on their use (or non-use) of insurance.

“The proper perception of risk factors is the first step towards creating an effective risk management system. From this point of view, the surveyed farmers were able to acknowledge correctly the most important agricultural risks”, according to a Polish study.

Taking out crop insurance – which compensates for crop losses due to extreme weather events – is the top strategy cited by farmers surveyed in Poland.

In France, the story of crop insurance – also known as comprehensive climate insurance (assurance multi-risques climatiques : “MRC” insurance) – is quite different.

Systems for compensation of losses due to extreme weather events are inherited from national history, at times in parallel with the establishment of the CAP. Climate risk is keenly felt in France, a mosaic of different climates and terroirs. France’s Agricultural Disasters Scheme (Régime des Calamités Agricoles) dates back to 1964, two years after the launch of the historic CAP focused on securing food supply (and a former system, settled back in 1933 : The French State had created the National Lottery for the benefit of veterans (the “broken jaws”) and agricultural calamities). The scheme has undergone a number of changes over the decades. Like any form of national aid, it must comply with the provisions of European regulations, and was accepted by the EU’s “exemption regulation” of June 25, 2014.

Article L-361-5 of the French Rural Code defines agricultural disasters as: “damage resulting from risks, other than those considered insurable, of exceptional importance due to abnormal variations in the intensity of a natural climatic agent, when the technical means of preventive or curative control normally employed in agriculture, taking into account the production methods considered, have not been used or have proved insufficient or inoperative”.

In France, protection systems include crop insurance, and also the Agricultural Disasters Scheme which is subsidised by the FNGRA (national fund for agricultural risk management). The coexistence of different protection systems has invited criticism: “One of the main criticisms, apart from the complexity of [comprehensive] crop insurance, is the link between the agricultural disasters system and the crop insurance system. There is competition between these two systems […]. For example, consider two livestock farmers in the same area. Farmer (A) is insured, farmer (B) is uninsured. Farmer (A) has suffered substantial losses, but the calculation of crop losses […] results in a percentage of losses below the payout threshold. He is therefore not compensated. Farmer (B) suffered the same percentage of crop losses and, like farmer (A), is located in a municipality eligible for the FNGRA [agricultural disasters scheme]. He is therefore compensated […]” (D. Kapsambelis, PhD thesis 2023).

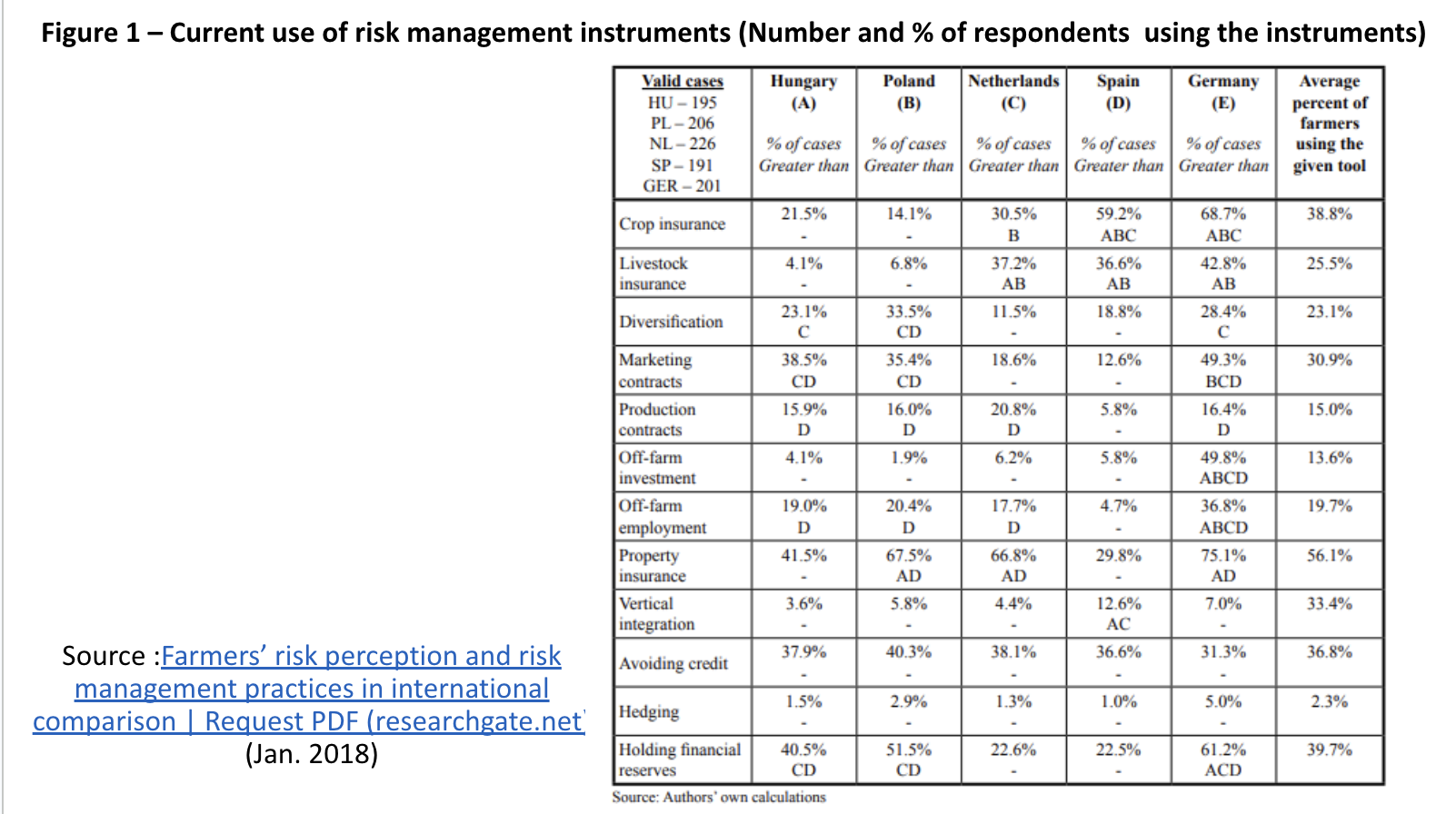

Paradoxically, French farmers perceive taking out insurance as an additional risk. Indeed, studies have shown that farmers’ investments in protective equipment (such as heaters to combat frost, or nets to protect against hail) were inversely proportional to their investments in insurance coverage. Furthermore, the price of insurance, considered too high by French farmers, is a known obstacle. Finally, the rate of insurance coverage is half that of Germany. In 2022, only 17% of insurable farmland was covered by crop insurance. This despite the fact that, since 2005, part of the insurance premium has been subsidised by the CAP (30% of insurable land excluding grassland, 17% including grassland, which is still well below the German figures of 15 years ago – see Figure 1). It should be noted that 30% of UAA excluding grassland was covered by single-peril insurance (hail, frost) not subsidised by the CAP.

Among French farmers’ misgivings is a very technical yet highly strategic detail. The reference yield (used as a basis for comparison with the yield obtained during the extreme weather event) is based on the Olympic average, i.e. the average yield over the previous five-year period, where the best year and the worst year are dropped. The Olympic average adheres to climate realities, and is set to plummet with the accumulation of bad years, as was observed in the 2010s. Insurance has not even established itself in the French countryside and it is already reaching its limits. Meanwhile, France is experiencing a higher rate of global heating than other parts of Europe.

In addition to these finer points of calculation, French farmers are conscious of events that have fuelled mistrust of the insurance system in recent years: the drop in premiums paid in 2013, and the outrage of cafés and restaurants who received no compensation from their insurers during the COVID-19 crisis and lockdowns.

Adaptation in national legislation

Germany and France have both changed their legislation in recent years to combine the intensification of climate risk with the insurance system.

In spring 2015, Germany adopted a federal framework directive on the payment of subsidies to respond to damages in agriculture (and forestry) caused by natural disasters or adverse weather conditions.

This framework directive was notified to the European Commission on June 29, 2015. “Adverse weather conditions are defined as frost, hail, ice, heavy or sustained rain, storms not of hurricane force and drought. They are only confirmed if more than 30% of the average annual harvest of the [agricultural] business concerned or at least 20% of the forest is destroyed […] In the event of adverse weather conditions, compensation can represent up to 80% of the damage.” (French Senate Report, 2016).

Another interesting point, for a country whose farms have a high rate of insurance coverage: if the farmer has not taken out insurance for the greatest climate risks and covering at least 50% of the average annual harvest, the subsidy to which they are entitled is reduced by 50%. This system does not apply if the climate risk is so specific that insurance is not available at a reasonable cost in the private sector.

One more point to note: “in the absence of an absolute right to compensation [through insurance], it is the competent authority that decides on the granting of aid, subject to the availability of budgetary resources”. (French Senate Report, 2016).

The German directive refers to Commission Regulation (EU) No. 702/2014 of June 25, 2014 declaring certain categories of aid, in the agricultural and forestry sectors and in rural areas, compatible with the internal market, pursuant to the famous Articles 107 and 108 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).

In the German framework, the Federal Ministry of Agriculture states that agricultural risk management is primarily the responsibility of the farmer, who must take out appropriate insurance. The Federal Government, for its part, assumes responsibility for more systemic crisis management, by concluding, where necessary, administrative agreements with the Länder in which the adverse weather conditions occur.

In France, legislative changes came in 2022 with the Descrozaille reform. Named for an agronomist deputy in the Macronist majority, Descrozaille’s parliamentary report paved the way for the French legislation.

The first major difference: while Germany has a single framework directive for both main types of weather event, in France, the Agricultural Disasters Scheme, dating from 1964, is separate from the Natural Disasters Scheme. Even though both schemes may apply at the same time, ‘risks to farm buildings’ come under the Natural Disasters Scheme. Agricultural disasters in crops are compensated by the national fund for agricultural risk management (FNGRA).

A point of similarity with the German directive: crop insurance (which covers frost, hail, drought, excess water and storms) should be the farmer’s first line of defence against climate risks.

In addition to “a clear distribution of risks between farmers, insurers and the State”, this 2022 reform of the comprehensive crop insurance scheme is based on fundamental principles:

- Universality – providing coverage for catastrophe risks for all farmers, irrespective of sector. This has been a major issue for French arboriculture, which, despite CAP subsidies, had previously been very poorly insured / insurable. From January 1, 2023, all losses on all crops can be compensated up to 45%, above the deductible (around 30% in arboriculture and grasslands, around 50% in field crops and viticulture).

- Faster payouts – under the previous system, compensation could be paid up to two years delay ! This is a welcome move: such payouts support the viability of farms which are fragilized by extreme weather events.

Part of the debate focused on the deductible (which is standard for all types of insurance): where to draw the line?

According to Groupama, one of the two France’s biggest agricultural insurers, the cost of the comprehensive climate policy would rise sharply if the deductible were reduced from 30% to 20%, since such a measure would “not be compliant with France’s WTO commitments”, as per the Descrozailles report.

Ultimately the WTO restrictions were lifted: “producers will be able to benefit from coverage for policies with deductibles starting from 20% of crop losses (compared with 25% or 30% previously), and the subsidy rate [previously 35%] has been raised to the regulatory maximum of 70% as of January 1, 2023″ (French Ministry of Agriculture website).

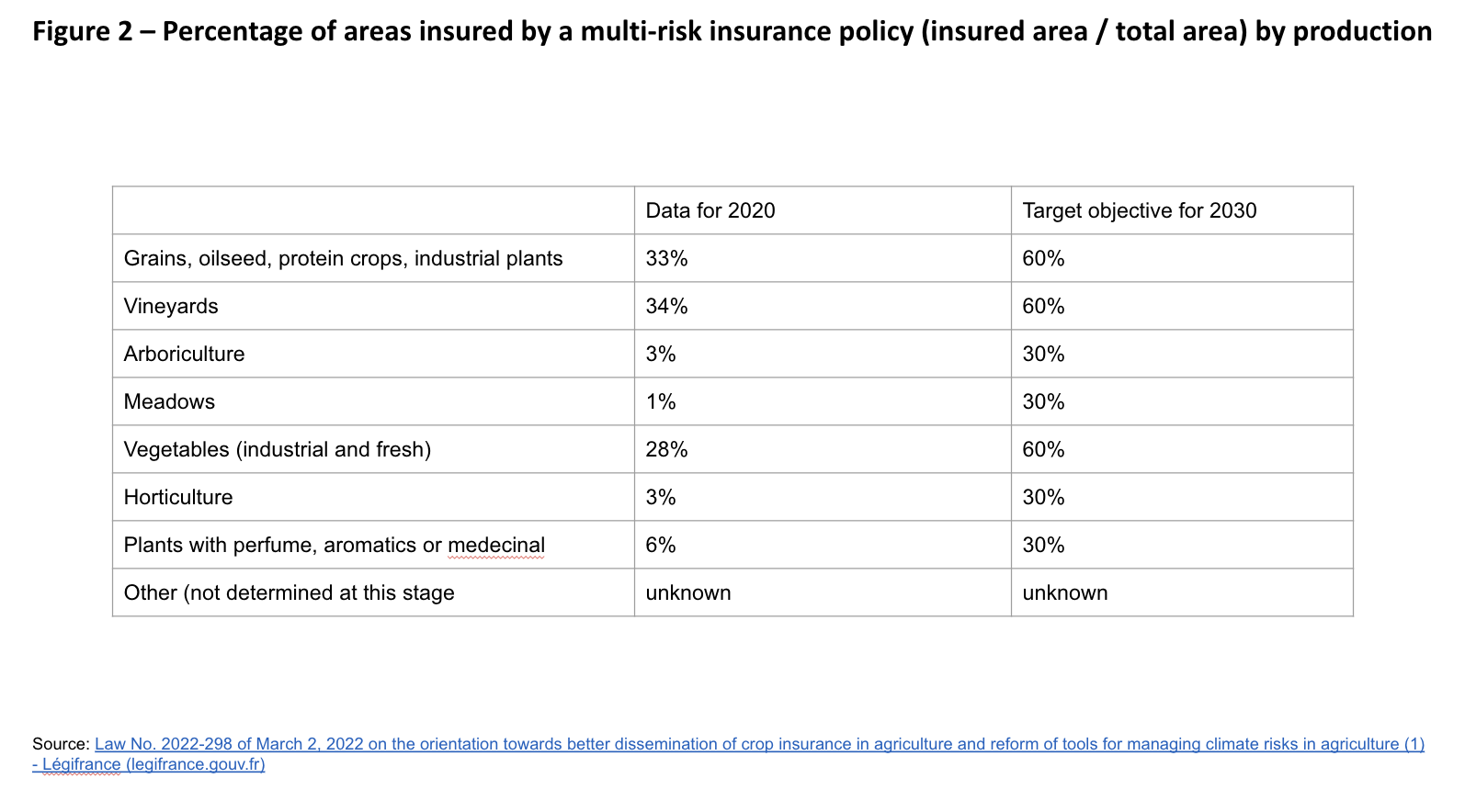

The goal is to offset the significant delay in coverage via crop insurance (see Figure 2), which is now subsidised by the EAFRD via the second pillar of the CAP pillar since the 2014-2020 programming period. The risk management toolbox proposed by the European Commission in 2005 was integrated into the 2008 CAP reform under the first pillar, before the second pillar took over in 2014.

Short-term Conclusion

In France, when the general interest is neglected, there is a saying: “Every man for himself, but God for all”.

On the subject of water scarcity, and the much-feared risk of drought and many more extreme weather events, suffice to say: “Every man for himself, mega-basins built with public money for the few, but crop insurance for all… that is, all who can afford it with all the hurdles faced by the insured farmer”.

Compared to their European neighbours, French farmers don’t really believe in the ‘insurance’ God. And this mistrust persists, despite CAP subsidies for crop insurance policies, first via pillar 1, then pillar 2. Note that both alternatives – the ‘irrigation insurance’ of mega-basins, and crop insurance – have a subsidy rate of 70%! All seems well designed and anticipated.

So, as a last resort, we can let ourselves be won over by optimism: there will always be national solidarity… or won’t there? The mobilisation of the water convoy seems to bring a positive impact: “Two prefectoral decrees authorising the creation of fifteen water reservoirs for agricultural irrigation in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region were annulled on Tuesday 3 October by the Poitiers administrative court, which ruled that they were unsuited to the effects of climate change” (souce : le Monde, October 3rd, 2023).

In part 2 of this policy analysis, looking at reinsurance, aka ‘the insurers’ insurance’, when enormous and systemic risk is involved, we’ll go a step further in understanding the resilience of European agriculture’s systems of resilience, which are exposed to increasingly severe and frequent extreme weather events.

In 2023-2024, the Rural Resilience project embarks on a new phase of joining the policy dots while continuing to nurture what we have built together, and widening the lens from France to Germany and the broader Europe. To learn more, visit the project page, and follow ARC2020 on LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook or Instagram.

Read More

Access to Land: More Resilient Agriculture – Without Any EU Legislation? (Part 2)

Access to Land: Looking to Europe to Secure Local Farmland? Part 1

Beyond the Harvest: Health Effects of Pesticides on French Farmers

France | Democratising Food Policy – Tweaking The Financial Toolbox

Ernährungsrat: The democratic potential of Food Policy Councils in Germany