In the third in our milk crisis and farm income debate series, Alan Matthews suggests that supply management is not the way to improve price and income.

The weighted average milk price for the EU-28 in May was 26.6 c/litre, a price last seen during the last trough in the price cycle in 2009 when the milk price bottomed out at 24.39 c/litre. The reasons for the current downturn are well known.

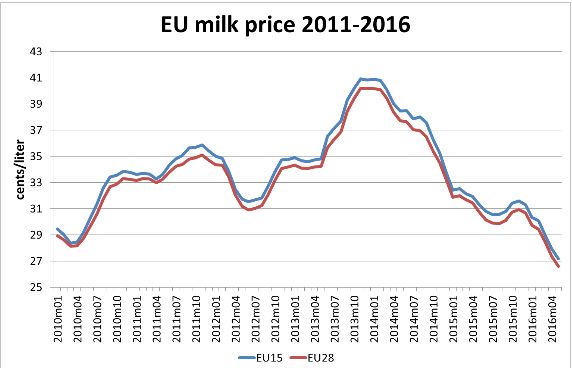

Global dairy product prices reached record levels in 2014. EU milk prices reached a record high of 40.2 c/litre in the winter of 2013/2014, averaging 37.3 c/litre over the 12 months in 2014. Milk supplies around the world responded to these high prices in the expectation of an inexhaustible demand for dairy products from China. Increased supplies were facilitated in the EU by the removal of quotas in April 2015 although expansion had begun long before. EU production increased by more between the years ending April 2014/2015 when quotas were in place than it has done between the years ending April 2015/2016 after quotas were removed.

Unfortunately, the expected growth in demand did not materialise. China left the market, low oil prices hit demand from oil-exporting countries which were traditionally big buyers of dairy products, and Russia banned imports of dairy products from the EU. This sent EU milk prices into free fall, as shown in the chart, with no sign as yet that the trough has been reached.

Source: Milk Market Observatory

A number of member states and farm groups have called for the introduction of supply management measures in the EU to halt the fall in prices. But the term ‘supply management’ is used in very different ways. For the purposes of this article we can distinguish three different mechanisms, which are broadly similar to the three options set out in the recent French memorandum on this topic.

No member state has yet introduced a scheme under this Article, although some are still discussing it. The main difficulty it faces is the free-rider problem. A group of producers in one part of Europe agree to reduce production in order to raise the price, but this will simply encourage producers elsewhere to maintain or increase their production, thus offsetting much of the expected benefit.

The Article 222 mechanism. This mechanism is specified in the 2013 CMO Regulation and was involved by the Commissioner in March. It functions by lifting the competition policy prohibition on producers working together to raise prices at the expense of consumers. There is nothing to stop a co-op from paying its suppliers to reduce production at the moment. What is new in the Article 222 mechanism is that cooperation to reduce production can take place at the level of inter-branch organisations (thus involving several players on the market). It can also be funded by Member States, if necessary using the aid package they received from the EU budget last September. In March 2016, the Commission clarified that member states can use state aid to provide up to €15,000 annually over three years to farmers who voluntarily agree to reduce production.

The EMB’s Market Responsibility Programme (MRP). This is a regulatory scheme where supply reductions would be mandated under new legislation, presumably as part of a revised CMO Regulation. The MRP would be implemented in three phases, depending on the severity of the crisis. Phase 1 would introduce aids for private storage and measures to encourage consumption when milk prices begin to dip below some reference level.

In marketing its proposal, the EMB emphasises the voluntary nature of milk supply reductions in Phase 2 if milk prices continue to fall. Mandatory reductions for all producers would kick in during a severe crisis in Phase 3 (see the EMB’s contribution to this online debate). However, as part of Phase 2, all producers expanding production would be expected to halt their expansion. This would be ensured by means of a levy equal to 110% of the milk price. So benefits to one group of dairy farmers would be paid for in part by discriminating against other group of dairy farmers.

There are other arguments against the EMB proposal as a permanent part of the EU milk regime (for my evaluation of the proposal, see this recent report from the Committee of the Regions). However, for the purposes of the present crisis, the major drawback of a regulatory scheme is that it would require the passage of new legislation through the Council and Parliament. There is no legal basis for a regulatory scheme at the moment.

Voluntary supply reduction. This leaves the third option in the French memorandum of a voluntary buy-out scheme. This could operate as a buy-out scheme for dairy cows, or as an incentive to individual producers to deliver less milk over a specified period to their dairy. Funding might come from the EU budget or from Member States (though with national funding, the free-rider problem re-emerges). Recall that the Commission has already indicated it will approve member states paying state aid of up to €15,000 to farmers who voluntarily reduce production. I am not aware that any member state has taken up this option.

The main disadvantage of a voluntary scheme is that the producers most likely to sign up for it are those who were planning to reduce production or exit the industry in any case. There would thus be massive deadweight or slippage in a voluntary scheme, so it could end up costing a lot without having much impact on the overall EU market balance. There is also the danger that, by the time it was implemented and working, markets would have started to recover.

Given these drawbacks with supply management schemes, the Commission effectively kick-started a minor counter-cyclical direct payments scheme in September last year by contributing a €420 million package for dairy farmers, which member states could double from their own resources. It has also pointed out that Member States are able to make further state aid payments of up to €15,000 to farmers (maximum over a three year period) under de minimis rules.

Yet examples of policy incoherence abound. France, for example, is one of the main voices calling for dairy supply management, yet it persists in providing coupled aid to half of its dairy cow population, stimulating the very production which is causing the crisis. It is also one of the countries which has not made use of the EU-funded assistance package for its dairy farmers.

What the current milk crisis painfully exposes is the woeful inaction on the part of the dairy industry as a whole to prepare for milk price volatility. Milk prices were at a record high just two years ago, but what provisions were made to save for a rainy day?

The long-term answer to milk price volatility should involve a mixture of tax-incentive savings policies, risk-sharing milk contracts and milk price-related lending instruments (such as the MilkFlex loan scheme introduced by Glanbia in Ireland). Insurance products such as a margin protection progamme might also be investigated as part of an expanded risk management toolkit in the CAP. Supply management schemes in the dairy industry belong in the past.

Alan Matthews is Professor Emeritus of European Agricultural Policy at Trinity College Dublin and contributor to the capreform.eu blog.