When UK environment minister Owen Paterson visited the flooded Somerset levels on January 26, he forgot to take a pair of boots. The sort of oversight that could occur to any climate change skeptic, really. After a month of rising floodwaters, local residents were quick to spot the limitations of the minister’s street shoes, which were clocked by the Daily Mail. What might have been a ministerial wade-about turned into an awkward stand-off in the middle of a media scrum.

When UK environment minister Owen Paterson visited the flooded Somerset levels on January 26, he forgot to take a pair of boots. The sort of oversight that could occur to any climate change skeptic, really. After a month of rising floodwaters, local residents were quick to spot the limitations of the minister’s street shoes, which were clocked by the Daily Mail. What might have been a ministerial wade-about turned into an awkward stand-off in the middle of a media scrum.

Had the minister been briefed? Thanks to a Freedom Of Information application, his briefing notes for the visit can be downloaded here. It is a useful document packed with practical background notes: 18% of Somerset (635 sq kms) is below sea level, requiring artificial raised river banks for the main waterways that cross the moors. If these overflow on to the moorland below, the water cannot be returned to the rivers until water levels drop.

Flooding is not new to these parts: in 1919 280 sq kilometres of Somerset flooded, compared to 65 sq kilometres this year. The flood defences built in previous years were funded at 85% by central government through the former agriculture ministry MAFF.

However, as DEFRA civil servants note: “…Government policy and priorities have changed from protecting agricultural land to protecting people and property. In the current economic climate, we are unable so far to attract local funding to continue to maintain the ageing infrastructure which does not protect people and property.” A few days later, Environment Agency chairman Sir Chris Smith was hammered very publicly by communities minister Eric Pickles, for having stuck to this policy guideline. “I’ve made it clear that government makes policy and we implement it,” Smith told The Guardian afterwards.

For the flood victims on the Somerset Levels, the immediate problem has been overflowing rivers which have not been dredged and cannot drain to their full potential. When Paterson arrived on the scene, he could not promise 100% central government funding. His guidance was clear: “Under the Government’s partnership funding policy we are unable to justify the full funding of this work.”

In a carefully-worded passage, his DEFRA briefing explains that expenditure must be shared with partners, be they regional or local stakeholders: “Partnership Funding was introduced to make sure that investment in flood management is not constrained by what Government alone could afford to do, to increase certainty and transparency over the level of Government funding for each project, and allow a greater level of local ownership and choice.” However, this was no time to pass the hat round.

Working on the basis of an estimated GBP 4 million requirement to dredge the rivers Parrett and Tone, DEFRA had been talking to local stakeholders, including Somerset County Council, Wessex Regional Flood and Coastal Committee and the Environment Agency to secure pledges worth GBP 1.5 million. Glastonbury festival founder, dairy farmer Michael Eavis, whose events have raised millions of pounds for good causes, is working to raise funds to kickstart dredging work and help his flooded neighbours. In an article in the Daily Mail, he blasts the “clowns” at DEFRA, accusing the ministry of putting biodiversity before farmland: the Daily Mail loves reporting this kind of fighting talk.

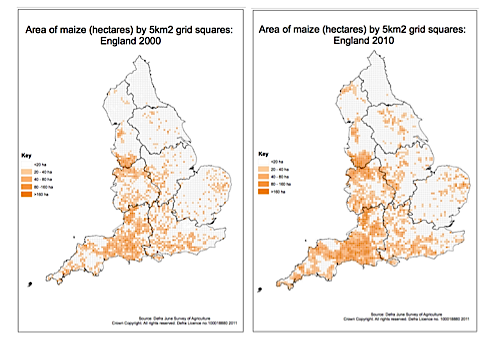

Two weeks later, environmental journalist George Monbiot literally stirred up the muddy waters engulfing this crisis, pointing out that a lot of silt was coming off maize fields. According to DEFRA data highlighted by fellow environmentalist Miles King, and referred to by Monbiot in a footnote, this forage crop has displaced barley and wheat hectarage in the south west. The maps here show the density of maize cropping in 2000 and 2010 as presented in the original DEFRA document.

Two weeks later, environmental journalist George Monbiot literally stirred up the muddy waters engulfing this crisis, pointing out that a lot of silt was coming off maize fields. According to DEFRA data highlighted by fellow environmentalist Miles King, and referred to by Monbiot in a footnote, this forage crop has displaced barley and wheat hectarage in the south west. The maps here show the density of maize cropping in 2000 and 2010 as presented in the original DEFRA document.

It is the kind of environmental conundrum that confounds rational debate. Despite longstanding warnings of the soil erosion risks of maize and shortlived requirements to counter soil erosion after cropping maize, this exotic forage crop has preferential treatment under Good Agricultural and Environmental Conditions (GAEC). Monbiot traces this back to 2010, but there is an earlier appearance of the same escape clause for maize in the 2007 Cross-Compliance Guide on page 27 – the only appearance of the word “maize” in the whole document. The lack of a GAEC requirement to prevent soil erosion after maize harvesting may go back as far as 2005, since it is not listed as a new departure from the 2005 and 2006 GAEC requirements.

The favourable treatment of maize is not limited to England, however. In France, ground cover for land under monocultures is a requirement from November 1 to March 1, with an exception being made for maize silage, for which the residues can be buried in the soil. In the case of flood plains, local flood prevention strategies would take precedence over cultivation strategies listed in the cross-compliance regulations.

Most maize grown in the UK or the rest of Europe, come to that, as Monbiot points out, is not heading straight for the human food chain. There is not only demand for animal feed, but a growing industrial demand in the UK for a different category of high starch maize to make bioethanol, too.

He also refers to a warning of the flood risk posed by maize growing in the south west that appeared in the journal Soil Use and Management late last year, just weeks before the flooding started. In a long term study of maize fields across the south west, RC Palmer of York and RP Smith of the Environment Agency’s Exeter office, found poor soil structure or run-off in 38% of the maize fields they examined.

Given Paterson’s belligerent backing for GM crops, come hell or high water (or both), coupled with the NFU’s unquestioning belief that GM crops are the future, maize plantings would rise even faster if GM crops ever get a green light. What with silt and glyphosate run-off, any future environment minister planning to visit flooded Somerset Levels would need more than wellington boots.