Photo courtesy of Rasmus Blædel Larsen

Wednesday the 29th of November stakeholders and politicians from a wide spectrum of the Danish agri-world convened at the parliament to discuss: Who Shall Own the Land? By Rasmus Blædel Larsen, PhD.

The Danish context around agricultural land

The upshot of the day-long conference is a growing concern in Denmark, that foreign investors are buying up the agricultural land. Or at least that is the rumor among farmers, what actually unfolds in the Danish land-market is clouded in secrecy. At the heart of the matter is the lack of a ownership-register or monitoring entity, which could provide clarity and transparency as to who actually owns the Danish agricultural land.

To understand the situation – or let me be academic – to help the readers grasp some of the underlying factors of why there is no trustworthy data on ownership, we need to take a look at the so-called ‘structural development’ and the generic Danish finance-model.

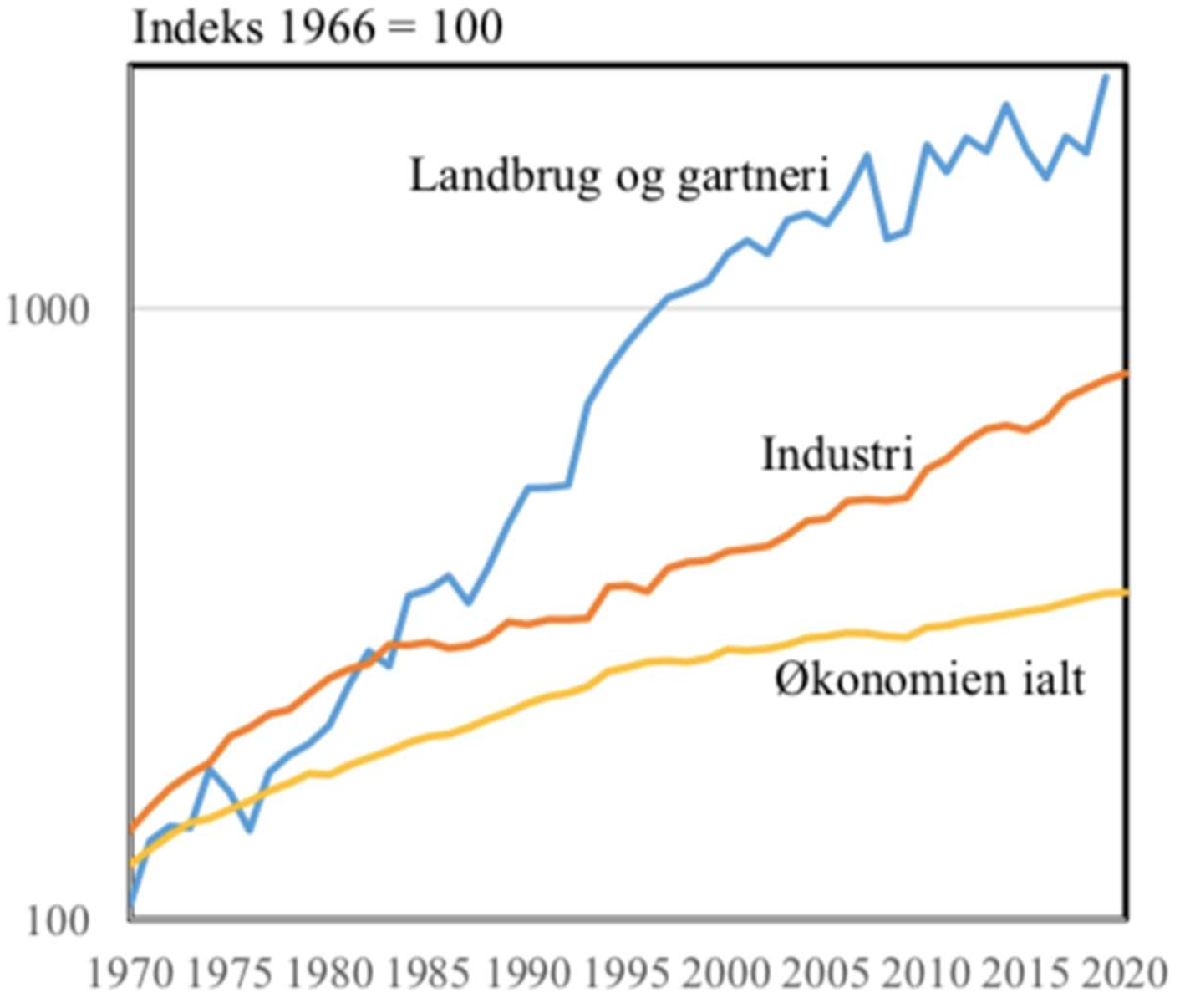

The conference began with a presentation heavy in numbers, figures and graphs, documenting how Danish agriculture is characterized as an export-driven sector where 80% of the produce is targeted the world-market. The Danish pig-and dairy-producers are organised in two global coops: Danish Crown and Arla. Arla is now an international coop, with farmers in 7 EU member states listed as owners: Denmark, Sweden, Germany, Luxembourg, Holland, Belgium, and England. The coops have succeeded in keeping their products competitive – in the face of much higher salaries in Denmark than most other countries – by guiding their owners towards investing heavily in research, hightech and large-scale production-advantages. In doing so, we were told at the conference, that Danish farmers have been able – over the past 30 years – to achieve twice the growth in productivity compared to all sectors in the Danish economy.

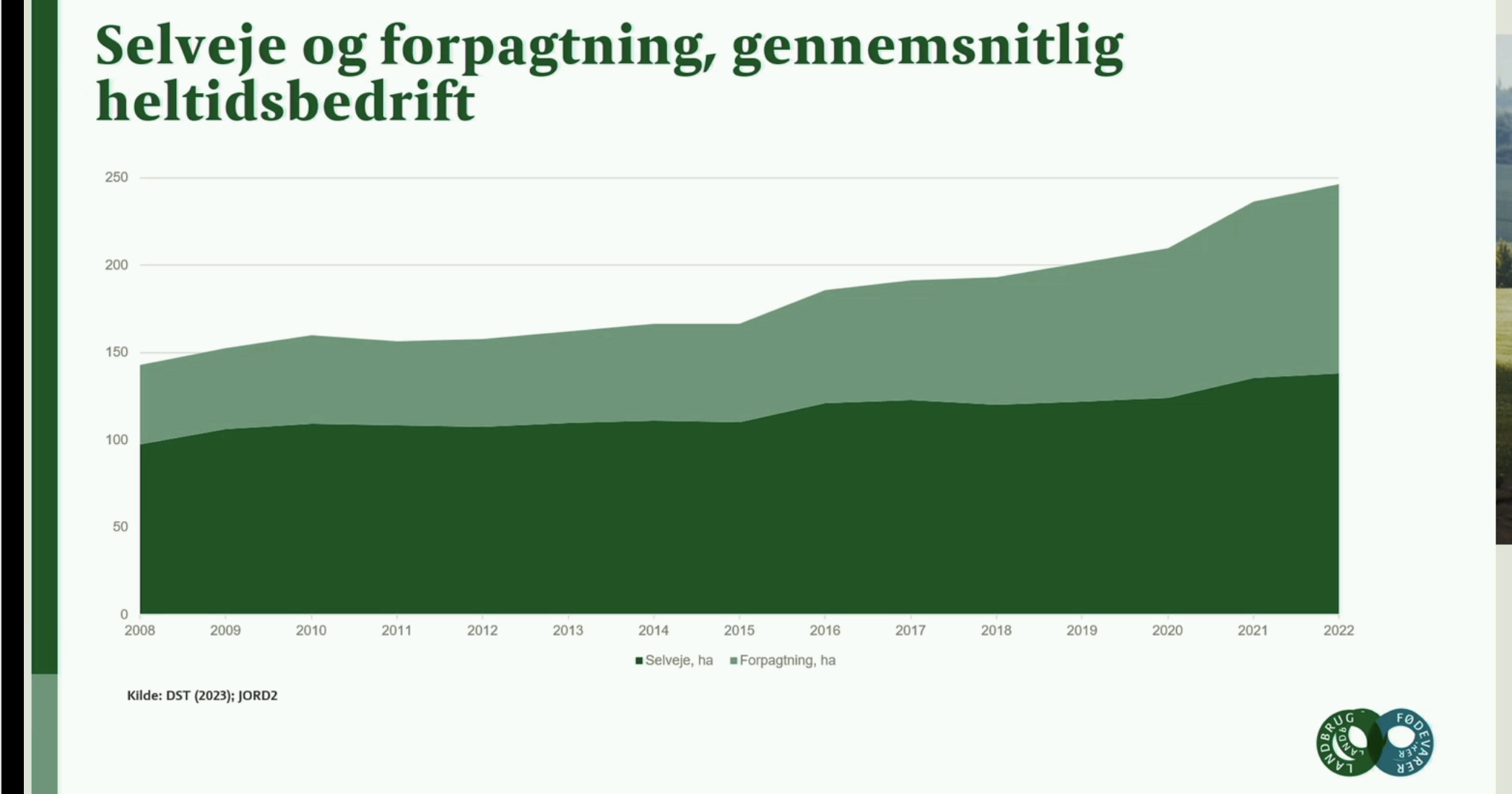

The structural development is in other words another name for the farms growing in size while implementing knowhow and pioneering technological production-set ups e.g.: micro-management of nutrients, completely automated systems; and drones and self driving tractors in the field. In order to finance investment in the newest technology/solutions you need more land/more pigs and cows to make the investment viable – thus there is a constant rush among the farmers to buy more land. More critical voices within the farming community calls this development ‘cannibalistic’. The facts are that ten years ago we had 11.800 farms, as of 2023 there are 7200 full time farms left. Every day 1-2 farms close and are bought up by their neighbors. But nowadays it is not only farmers who are in the market of buying up farmland – energy companies, individual investors, pensionfunds and other unknown actors are pushing the prize of land upwards and threatening the business model in Danish agriculture. In less than a decade the percentage of land owned by the farmer versus the amount of land he has to rent from other owners has changed dramatically and today it is close to half-half.

The Danish model

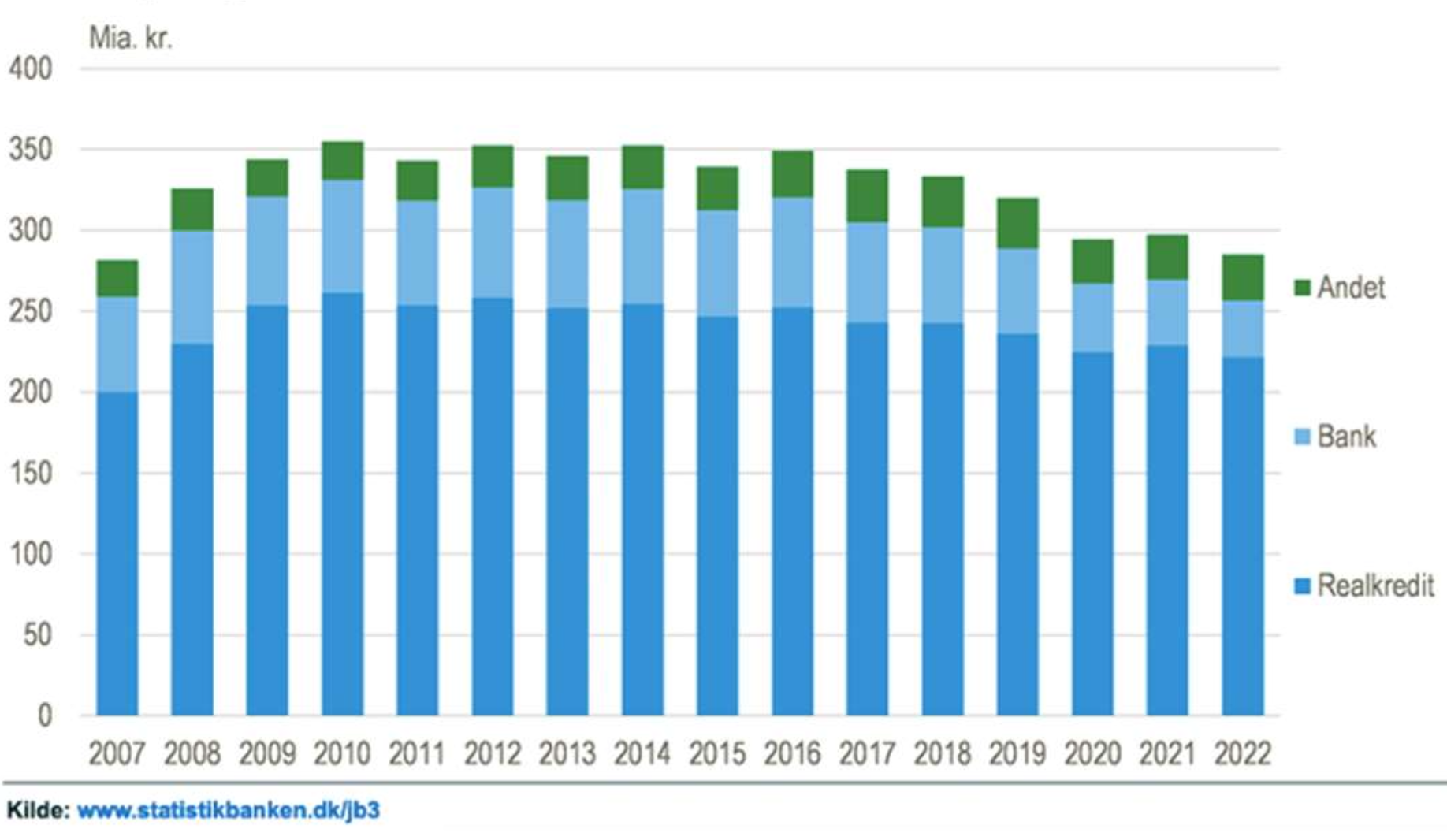

The Danish finance-model for agriculture is quite unique. It has similarities to the coop-model and was constructed around the same time: in the 1870s. Simply explained when you want to buy a farm or more land, you go to the ‘coop-credit-institution’ and ask for a loan, with which you proceed to the bank and ask for the rest of the money you need. The ‘coop-credit-institution’ is run by the farmers themselves and they collectively put up their assets as security, so once you have the green light from your colleagues – the banks have traditionally ‘rubber-stamped’ the loan. This system has made the structural development in Denmark possible but also Danish farmers the most heavily indebted farmers in the world! This also lies behind the Danish stance on the CAP-reforms.

It should be noted that this credit-system is in fact not in compliance with EU-laws as it gives Danish farmers an unfair capital/investment advantage and does not adhere with the financial regulations post-2008. However Denmark was able to negotiate an exemption when the country entered the Union in 1973 (back then no one could foresee that the system would produce the situation we are currently facing) – and the system still persists – in fact this summer another 12-year adjustment period was given.

The increase in farm-size has put constant pressure on the national regulations and finally in 2010 – in the wake of the financial crisis which swept through the global economy and exposed the Danish agricultural economy – the agricultural law was all but abandoned, though one crucial regulation was kept in place at the behest of the farmer’s organisation: The farm must be run by a farmer – aka a person who has taken a certificate from a Danish farm-school. This regulation was abandoned in 2014 – and a new phase in the history of Danish agriculture became reality.

It is widely acknowledged that it was the financial sector who demanded this final liberalisation – and it was also reiterated at the conference – and it is the same sector which argues that in order to attract investors to Danish agriculture, it is crucial that they can remain anonymous. And so it is, today no one in Denmark, not the Minister for Agriculture, not the researchers and experts, nor the farmers themselves, knows who are buying up the land or how much is owned by whom. For many reasons, among them democratic legitimacy and national security, it seems peculiar that Denmark should allow this model – and the situation has caused a heterogenous group of farmers and stakeholders to unite.

Building a land owner register

In 2021 a broad coalition: Who Owns the Land was formed in order to work – or lobby if you will – towards getting a land-owner register.

In the early spring of 2022 – with the war in Ukraine as a backdrop – the minister acknowledged that the situation perhaps was untenable and tasked an ‘inter-departemental working group of legal experts’ to clarify the ‘international legal situation’ and possibilities of regulating foreigner’s access to buy land in Denmark. It is disputed whether such a report was really necessary – in 2021 EU funded a report: Agricultural land market regulations in the EU Member States, which analyzed and summarized the legalities surrounding this theme in all 28 member states.

“Given the importance of land and the functioning of land markets, it is not surprising that government interventions that influence the land market are widespread.(…)Large differences in agricultural land market regulations exist between countries. Institutional, economic and political factors have had an impact on how farmers are accessing land (rental versus ownership-cultivation) and the regulations that are in place (Swinnen, 2002; Swinnen, Van Herck and Vranken, 2016). These historical factors have resulted in different land market developments so that there is no ‘one size fits all’ set of regulations that is optimal for all countries. While some countries have heavily regulated markets (e.g. Croatia, Hungary, Poland and Romania), other countries have a very liberal approach to land markets (e.g. Czechia, Denmark, Ireland and Finland).(…) Nevertheless, foreign investments can have beneficial effects as they can contribute capital, technology and know-how, thereby improving the productivity of the agricultural sector. However, the acquisition of land by (foreign) investors yields benefits only when information is evenly accessible and when markets are competitive (e.g. when property rights are clear and enforceable). Asymmetric information can be a source of speculation. Individuals often have a disadvantage in transfers with corporations, as the latter often have better access to information and a wider (political) network. “ (Vrankens et al 2021)

The report concludes that among the 28 member states only Denmark and Ireland have virtually no regulations as regards the land market, but in the latter case “The cultural association of land and ownership is very strong in Ireland; hence, the land market is very small. Most of the land transfers are either moving land from one generation to another or through the rental market.”;

whereas in Denmark “The potential for companies to own agricultural property has increased since 2010. Investors – Danish or foreign – can form a company that can acquire an agricultural property.” (ibid.)

However the Minister and Danish politicians in general when confronted with this report, maintained that due to the GDPR-directive and the ‘Anti Money-Laundering directive’ (AML) it was complicated and probably illegal to establish a register of owners.

Further political discussion was put on hold, until the working group delivered their report, which was supposed to be autumn 2022, then spring 2023, then summer, then autumn – and then finally just a few weeks ago the report was published. It is a 23 pages report and on page 18 the following statement can be read:

“With the implementation of AML 4 and 5, a number of measures has been implemented to make it more difficult for companies to hide the actual ownership within a complicated structure. The regulations however does not prevent the possibility of hiding the actual ownership; and therefore the information about actual ownership in the register can not be guaranteed to be correct, and therefore we can not be sure if the company has clouded the ownership within a complicated structure, behind which the actual owner hides.” *

The report also stated that it was legal to create barriers for foreign investors buying up agricultural land, indeed that it was widespread to do so. The minister responded by sending out a press release, that he was tasking the national institute for statistics with compiling a yearly update on how much soil is owned by ‘entities outside the EU’.

The first of these updates is to be published at the end of 2024. However it remains unclear if it is within the mandate, to register or try to seek out the actual owners of the soil.

Where things stand

Which leads us to the current situation and the conference at the Parliament.

The conference was organised by the coalition Who Owns the Land, and was an attempt to use the current attention to the issue, to further a political commitment to transparency. A large part of the day’s program was set aside to establish the interconnectedness between the structural development, ownership of the land, national security, biodiversity, CO2-emissions, nature restoration, sustainable energy-production, the water framework directive as well as the conditions young farmers who wants to establish themselves face. The chairman of the young farmer’s organisation, Landboungdom, Anders Bach, a junior division of the conventional farmer’s organisation (L&F), presented his thoughts. The Family Farmers, also part of L&F, represented by their chairman Lone Andersen, vice-chairman of L&F, and chair of Copa-Cogecas organic working group, gave her perspectives – both expressed concern about the disappearing of small ‘affordable’ farms.

The four national soil-foundations were all represented by their CEOs – of which the largest: Danish Organic Soil A/S owns in the vicinity of 1.000 hectars – as well as organisers from the slowly growing movement of CSA-agriculture. During their presentations, apart from highlighting their individual achievements, the common goal to raise public awareness about predominantly environmental issues and through that funds for buying up more land to be leased to small organic producers, were in focus. A good mix of researchers – among them several legal experts interested in the topic – were also present and from the Parliament came three MPs. Unfortunately none from the current government, nor from the financial sector were there.

Even so, when asked directly by one of the legal experts, if any of the present MPs and the parties they represent were willing to actively work towards creating a transparent ownership-register, none of the MPs answered the question. The left wing instead articulated an interest in creating a publicly owned ‘Soil-fund’ to combat climate change; while the right wing welcomed foreign investors and thought abolishing taxes on land-deals could help young farmers. The center-right of Danish politics – represented by a part-time farmer full of anecdotes about his part-time job – had not studied or been briefed about the situation and had a curiously stubborn disbelief as to why the conference had been convened in the first place. He maintained that all owners of land could be found in the national company-register. His lack of knowledge or interest could probably be said to be mirroring a wider lack of interest in the topic from the Danish public.

It is probably within the nature of such events that each actor when presented with a stage and a high-profiled audience will seize the opportunity to speak about his/her main prerogative – but it is rather disappointing that the gathering of so many influential stakeholders on such a topical question, in the Parliament, that these people were unable even to address the central questions: Who shall own the Danish land and are we allowed to know. The answer is still blowing in the wind.

—

*The original Danish text: Med implementeringen af hhv. 4. og 5. hvidvaskdirektiv, er der således indført en række skridt mod at sikre sig, at det er sværere for virksomheder at skjule deres reelle ejerskab i en kompliceret selskabskonstruktion. Reglerne medfører dog ikke, at det er umuligt at skjule ejerskabet, og der er derfor aldrig en garanti for, at oplysningerne om de registrerede reelle ejere i CVR.dk er korrekte, og at selskabet ikke har forsøgt at sløre ejerskabet bag en kompliceret ejerkonstruktion, hvor den reelle ejer gemmer sig.

Read More…

Access to Land: More Resilient Agriculture – Without Any EU Legislation? (Part 2)

Access to Land: Looking to Europe to Secure Local Farmland? Part 1

Rural Europe Takes Action | Creating Alternatives, Creating Community