Fifteen years on from the ‘land rush’, a multi-pronged global land squeeze is forcing farmers and communities off the land – and Europe has a key role to play in fixing it. By Nick Jacobs.

After a 15-year hiatus, land grabbing is back in the headlines. It recently emerged that some 25 million hectares of land in five African countries have been snapped up by Blue Carbon, a Gulf-based firm that brokers carbon offsets. Already covering a staggering 10% of Liberia’s surface area and 20% of Zimbabwean land, further deals appear to be in the works with Angola and other African governments.

In the years following the 2007-2008 global financial crisis, we were hearing regularly about mega land grabs in Africa. With food prices spiking and food security rising up the agenda, prime farmland was snapped up by agribusinesses, sovereign wealth funds, and financial speculators. As these deals came to light, Europeans were shocked to find that a Dutch bank, a German coffee roaster, and a Swedish bioenergy firm were implicated in land grabs that were forcing African farmers and communities off the land.

The ‘land rush’ subsided from its initial peaks, and media attention waned. But the pressures on global farmland never went away. Fifteen years on, global land prices have doubled, land grabs are escalating in new and dangerous forms, and we are now facing a multi-dimensional land squeeze – as detailed in the latest report from IPES-Food.

What exactly has changed since 2008? Why are the pressures ramping up again now, and what does land grabbing look like today? And where does Europe sit in this picture? Here are some of the key dynamics.

#1. Agribusinesses are getting hold of land and resources by stealth

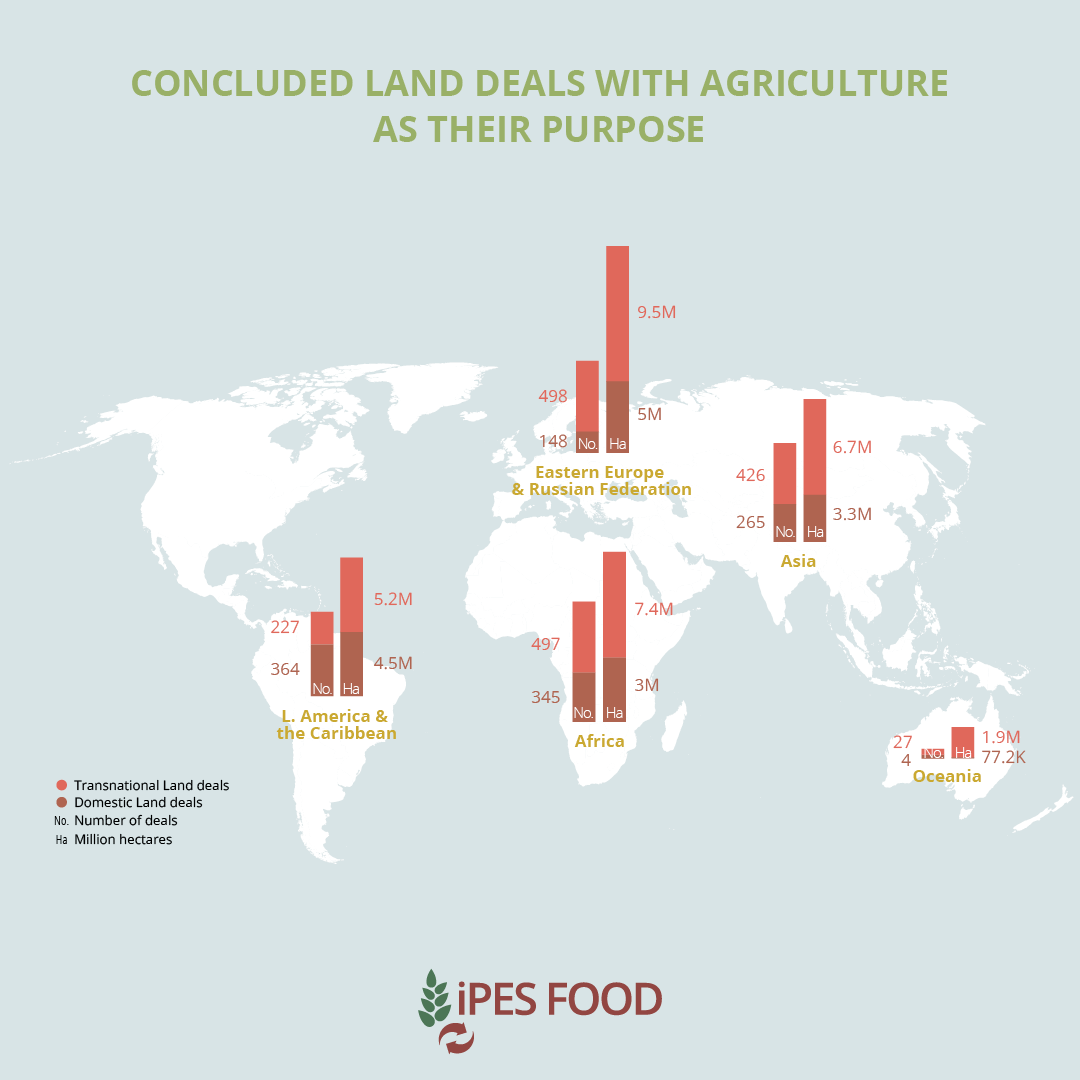

Today’s land grabs for export agriculture tend to be smaller, sometimes going under the radar. But their impacts on local communities are just as severe. ‘Water grabs’ are on the rise, with investors looking to secure control of critical resources and rapidly extract value from them. This is happening in areas that are already water scarce, including drought-stricken parts of Latin America. Eastern Europe also remains a major target for export agriculture land grabs.

But land grabs are only part of the picture. Recent mega-mergers have put huge price-setting power in the hands of giant agribusinesses. Through increasingly monopolistic practices, they are squeezing farmers’ incomes, saddling them with debt – and forcing small farms to ‘get big or get out’. In 2022, for example, a handful of dominant agribusinesses hiked fertilizer prices and increased their operating profits to 36%, even as they sold less product to farmers.

#2. ‘Green grabs’ are now the biggest threat to farmers and communities

Biofuels were one of the biggest drivers of the post-2008 land rush, and little has changed since. Remarkably, governments – including the EU and the US – are still incentivizing land conversion to biofuels through fuel blending requirements, and EU biofuel demand is expected to rise 11% this year.

But this time around, biofuels are only one piece of the food-land-energy conundrum. ‘Green hydrogen’ is being touted as the new ‘clean fuel’, but it requires considerable land and water – and wealthy countries are planning on using other people’s resources to do it. The EU wants 20 million tons of green hydrogen in the energy mix by 2030, and plans to import half of the total, primarily from North Africa. Initial projects are being developed on supposedly ‘marginal’ lands, but in reality these are often traditional rangelands and water scarce areas – leading to major impacts on farmers, pastoralists and local communities. Rising demand for ‘transition minerals’ is also contributing to a global mining boom that is eating up farmland, contaminating ecosystems, and displacing communities in some of the poorest places in the world.

But arguably the biggest threats are coming from burgeoning carbon offset markets. The evidence shows that carbon offsets fail to deliver actual emission cuts. Meanwhile, they regularly interfere with livelihoods. Before the ink had dried on the Blue Carbon agreements, it was clear that local communities had been insufficiently consulted, with reports that 700 members of the Ogiek People had been forcibly relocated in Kenya.

These concerns do not appear to be halting the carbon offset boom. As governments scramble to assemble net zero plans, they have pledged to allocate land areas equivalent to total global cropland for ‘carbon removal’. Financial speculators are also piling into a high-yielding market – expected to more than quadruple in value to $1,800 billion by 2030. Biodiversity offsets are also on the rise, as the flawed logic of carbon markets is applied to another huge environmental challenge.

These various forms of ‘green grabbing’ are on the rise, and account for some 20% of land grabs today.

#3. Out-of-control land markets are driving massive land price inflation and forcing farmers out

Financial speculation played a big role in driving food price spikes and land grabs post-2008. Since then, financiers have found new ways to unlock farmland investment, and the floodgates are now opening to a huge influx of capital. Agricultural investment funds rose ten-fold from 2005 to 2018, and now regularly include farmland as a stand-alone asset class. US investors have doubled their stakes in farmland since the pandemic. And through new financial derivatives, speculators are accruing and consolidating land parcels into bigger holdings, hiking up the prices, squeezing smaller farmers out of land ownership – and then leasing the land back to them.

Global land prices have doubled over the past 15 years and land inequality has skyrocketed – with 1% of farms now controlling 70% of global farmland – as financial speculation has combined with other land pressures. With land prices tripling in central-eastern Europe, soaring land values have been the final nail in the coffin for many small farms, which are disappearing rapidly from the European landscape. In Ireland and other parts of Europe, concerns are rising about the influx of billionaire landlords and the viability of rural communities.

#4. Governments are still rolling out the red carpet for investors – but land reform is also back on the agenda

Governments and global institutions faced scrutiny for their role in exacerbating the original land rush. But history is now repeating itself. Fifteen years on, the same players and the same playbook of pro-investor policies are fueling the land squeeze. The World Bank continues to incentivize countries to deregulate land markets through its latest index of business-friendliness, B-Ready. ‘Growth corridors’ are still springing up in Africa and Asia, despite being regularly linked with harmful land grabs and rights abuses. Sweeping investor protections are being inserted into trade deals, and increasingly used by investors to push through dubious land deals, oppose environmental policies, and sue governments who fail to comply.

And crucially, poorer countries are being encouraged to use their land and resources not just to feed wealthy countries, but now also to fuel their energy transitions and draw down their emissions.

Conversely, a number of governments and communities are pushing back and taking bold steps to fight land inequality and get land back into the hands of young farmers, sustainable (agroecological) small-scale producers, and marginalized groups. In Scotland, recent reforms have paved the way for community land buy-outs. And in Colombia and Brazil, major land redistribution schemes have been unveiled.

Europe must act to reverse the land squeeze – including in its own backyard

As the IPES-Food report shows, these and a wealth of other solutions are out there to halt the land squeeze and restore equitable access to land. For a region like the EU, the most urgent steps are to crack down on harmful carbon offsets, place community-led responses at the heart of biodiversity and climate policies, and embark on a truly sustainable and equitable energy transition that does not come at the expense of farmers and food security in the Global South.

But the land squeeze is also impacting European farmers and rural areas. As La Via Campesina argued in its calls for an EU Land Directive, “Without an EU agricultural land policy, it will not be possible to implement the Green Deal, the Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, the Farm to Fork Strategy, the Territorial Cohesion Policy or the Long-Term Vision for Rural Areas.”

This is even truer in light of the farmers’ protests that swept Europe this year. While instrumentalized by the far-right, legitimate grievances were raised about ratcheting costs and rising pressures on farming livelihoods, and the negative impacts of free trade and deregulated markets.

Putting land access at the heart of the Green Deal is therefore critical to make it a fair deal for farmers and rural areas, in Europe and globally – and to rebuild support for the social and ecological transformation that is so badly needed.

Read/Download the IPES-Food report on Land Squeeze (2024)

Nick Jacobs is the Director of the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food). He has led the panel’s work on food security, agroecology, and EU policy reform. Nick was a member of the European Commission’s Food 2030 Independent Expert Group, and previously worked in the support team to the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to food.

More

Access to Land: Looking to Europe to Secure Local Farmland? Part 1

Your Land, My Land, Our Land: Using International Legal Tools

Access to Land: More Resilient Agriculture – Without Any EU Legislation? (Part 2)

Cultivating The Future Together – ARC’s Rural Resilience Gathering in France