The EU spends a lot on CAP – almost 40% of its annual budget. But are these billions of euros delivering results? In a new report, the European Court of Auditors find the Commission is “overly optimistic” on the performance of CAP spending and needs to focus on the real impacts. It also confirms that 80% of direct payments are going to 20% of beneficiaries. Louise Kelleher reports.

The EU spends a lot on CAP – almost 40% of its annual budget. But are these billions of euros delivering results? In a new report, the European Court of Auditors find the Commission is “overly optimistic” on the performance of CAP spending and needs to focus on the real impacts. It also confirms that 80% of direct payments are going to 20% of beneficiaries. Louise Kelleher reports.

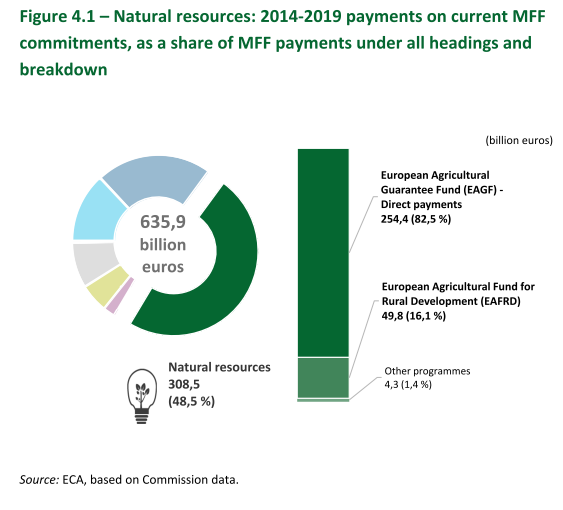

The European Court of Auditors (ECA) dedicates an entire chapter to CAP in a new investigation of how the EU budget performed up to the end of 2019. Sustainable use of natural resources – also known as header 2 of the Multiannual Financial

In their new report the auditors poke holes in the methodology for assessing CAP spending performance, critiquing weak indicators, a lack of focus on results, and the Commission’s over-rosy outlook. They then size up spending in light of each of the three general objectives of the CAP.

“Overly optimistic”

The Commission carries out its own high-level assessment of budget performance in the Annual Management and Performance Report (AMPR). But the auditors chide what they call “overly optimistic” performance reporting.

For instance in the management of biodiversity, soil and water, the Commission pats itself on the back for achieving over 85% of climate-action targets in the agricultural sector. But the auditors point out that correlation does not equal causation: these outputs were achieved in areas benefitting from specific measures in the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD), but they don’t demonstrate that the payments themselves had any effect.

There is no doubt that broadband access in rural areas has much improved (59% of households had next-generation access in 2019). However in the Commission’s rose-tinted view, this indicates that EAFRD is making an important contribution to rural development. In fact, there is no information to quantify EAFRD’s contribution to the broadband boom.

Limited intervention logic: outputs are not results

Limited intervention logic: outputs are not results

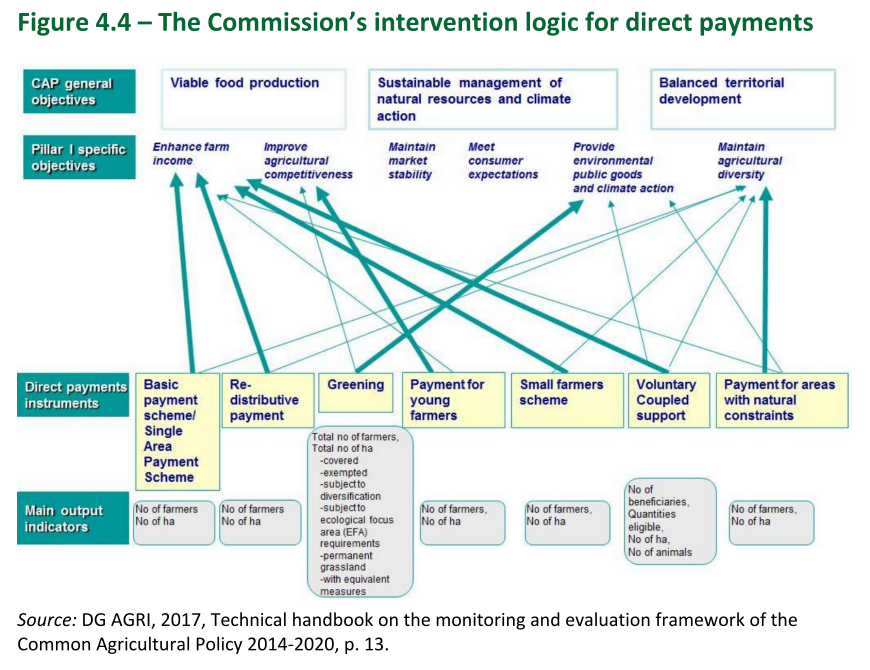

A key sticking point is what the auditors describe as a “limited intervention logic”. While the objectives of the CAP are connected with measures and output indicators, the Commission fails to identify needs as well as intended results and targets. This logic is flawed: policy performance cannot be reliably observed at output level.

Specifically for direct payments, it does not define the level of income the CAP aims to achieve for farmers.

For the EAFRD, Member States are required to correlate needs and measures in rural development programmes (RDPs) and to set targets for their result indicators.

The problem is, CAP indicators tend to be designed to measure outputs, and not results. The auditors warn that output indicators tell us little about progress towards meeting policy objectives. When seeking to measure results and particularly impacts, the influence of external factors must be taken into account.

While the auditors commend the Commission for factoring in the economic, environmental and social context in a number of indicators, overall the indicators fail to paint a clear picture of results.

Lack of monitoring data comes up again and again as an obstacle to analysing the impact of measures. It is impossible to identify milestones when targets are expressed only as directions (“increase”, “improve”) instead of quantified values.

Because the intervention logic and indicators are poorly designed from the outset, the Commission is unable to demonstrate that the CAP meets its objectives until it carries out evaluations.

The auditors have sounded the alarm on all of this in previous reports. And there seems to be progress: the Commission has revised the indicators and objectives in the post-2020 CAP proposals, and has recognised the need to further develop the indicators.

Is CAP spending meeting its objectives?

Moving on from the flawed methodology, the auditors next looked at how spending has delivered on the three general objectives of the CAP as well as relevant specific objectives. The general objectives are:

- Viable food production

- Sustainable management of natural resources and climate action

- Balanced territorial development.

Objective 1 – Viable food production

Spending on direct payments, rural development and market measures should in theory contribute to objective 1 of the CAP: viable food production.

Direct payments have made farmer incomes less volatile. But the auditors conclude that this instrument could perform better with more targeted spending and benchmarks for a fair standard of living.

80/20

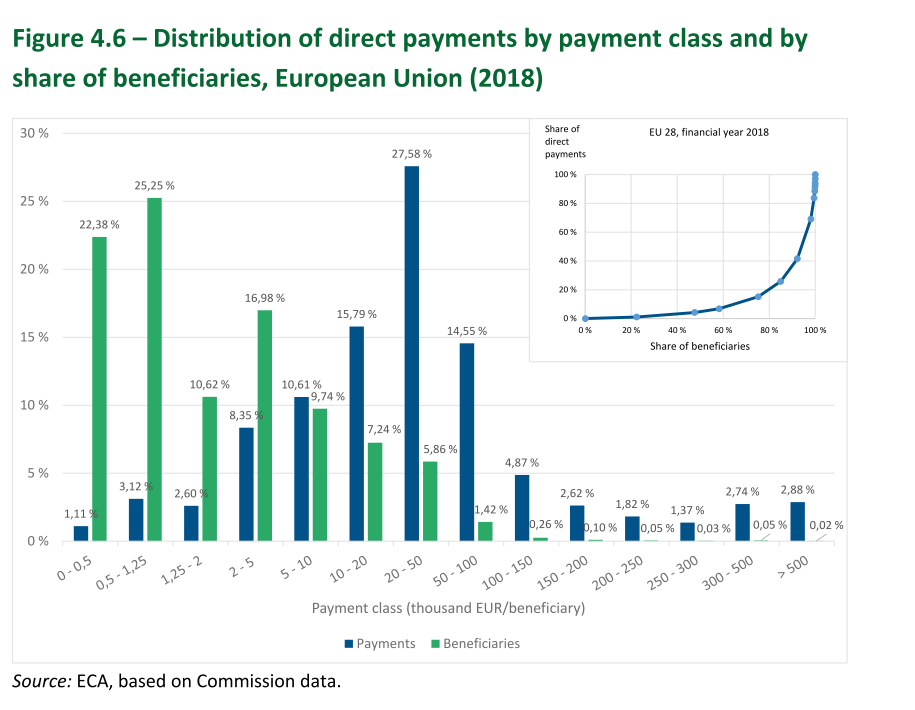

Some 80% of direct payments go to around 20% of beneficiaries. A closer look at these figures reveals that more than one-third of this money goes to only 2% of beneficiaries who receive over €50,000 each (see figure 4.6 above). Mechanisms designed to offset the skewed distribution of direct payments, such as capping and redistributive payments, have had little impact.

The problem is that although most farms in the EU are small (about two-thirds of farms were under 5 ha in 2016), direct payments are skewed towards bigger farms.

Astonishingly, there are no performance indicators to measure the efficiency of direct payments.

To improve policy design and make the CAP more efficient, we need to know how much money is ending up in the wrong hands. The auditors recommend identifying CAP funds paid “outside the target group” – to high-income farmers and non-farmers. This could also help flag instances of land concentration and land grabbing.

Meanwhile an evaluation published by the Commission earlier this month recommends investigating the impact of direct payments on the increase of land rents and appropriate countermeasures.

As for the effectiveness of rural development measures in supporting farm viability, the Commission rates the performance of these EAFRD targets as “relatively good”. But again, the indicators are unhelpful: instead of telling us how effective these measures are in supporting farm viability, they merely indicate the share of agricultural holdings which have received support. Due to the lack of data, it is impossible to assess whether or not this is money well spent. In any case, in January 2020 – on other words, six years into the seven-year budget – more than half of the EAFRD funds allocated for farm viability and competitiveness remained untouched by Member States.

Stable incomes versus standards of living

Stable incomes versus standards of living

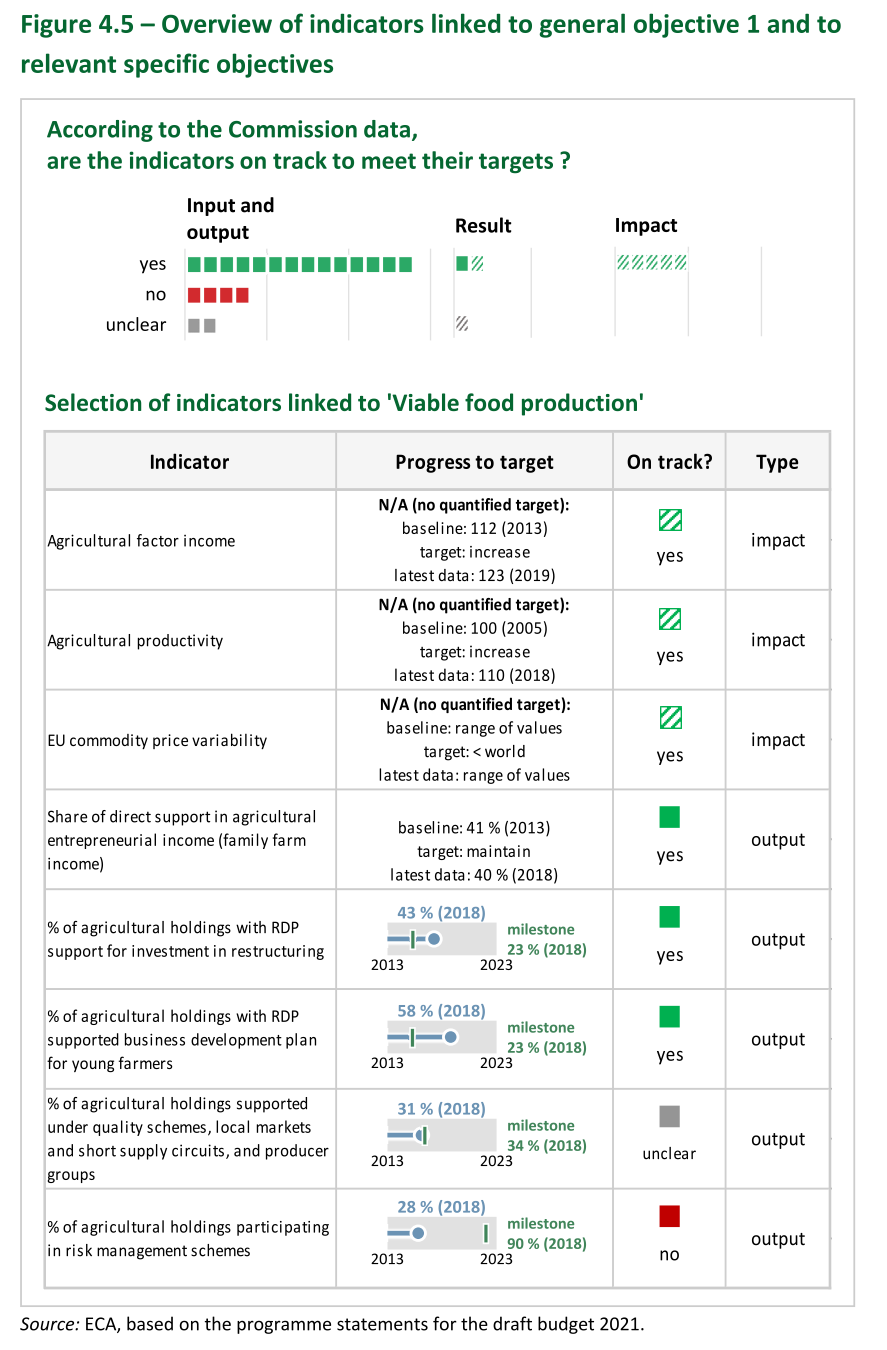

There are three specific indicators linked to the objective of viable food production:

- increasing agricultural factor income

- increasing agricultural productivity

- limiting price variability.

As can be seen in figure 4.5 above, all three indicators are performing well. However as the auditors note, the CAP has little to no demonstrable impact on these indicators, which in fact reflect macroeconomic developments.

Direct payments account for around 70% of CAP spending. The Commission’s evaluation suggests that direct payments have reduced farm income variability by around 30%, according to data for 2010-2015.

One specific objective of the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF) is to keep farmer incomes stable via direct income support. It is assessed by a single indicator – ‘Share of direct support in agricultural entrepreneurial income’ – which is also performing well, i.e. the ratio is stable. However this figure varies wildly between Member States. In 2017 for example, the share of direct support in agricultural entrepreneurial income was 8% in the Netherlands and 50% in Slovakia. This contradicts the policy objective of increasing the individual earnings of food producers while limiting the need for direct support.

Based on previous recommendations from the auditors, the Commission has proposed four indicators on agricultural income for the post-2020 CAP. But it stops short of collecting data on the disposable income of farm households to get a clearer picture of living standards.

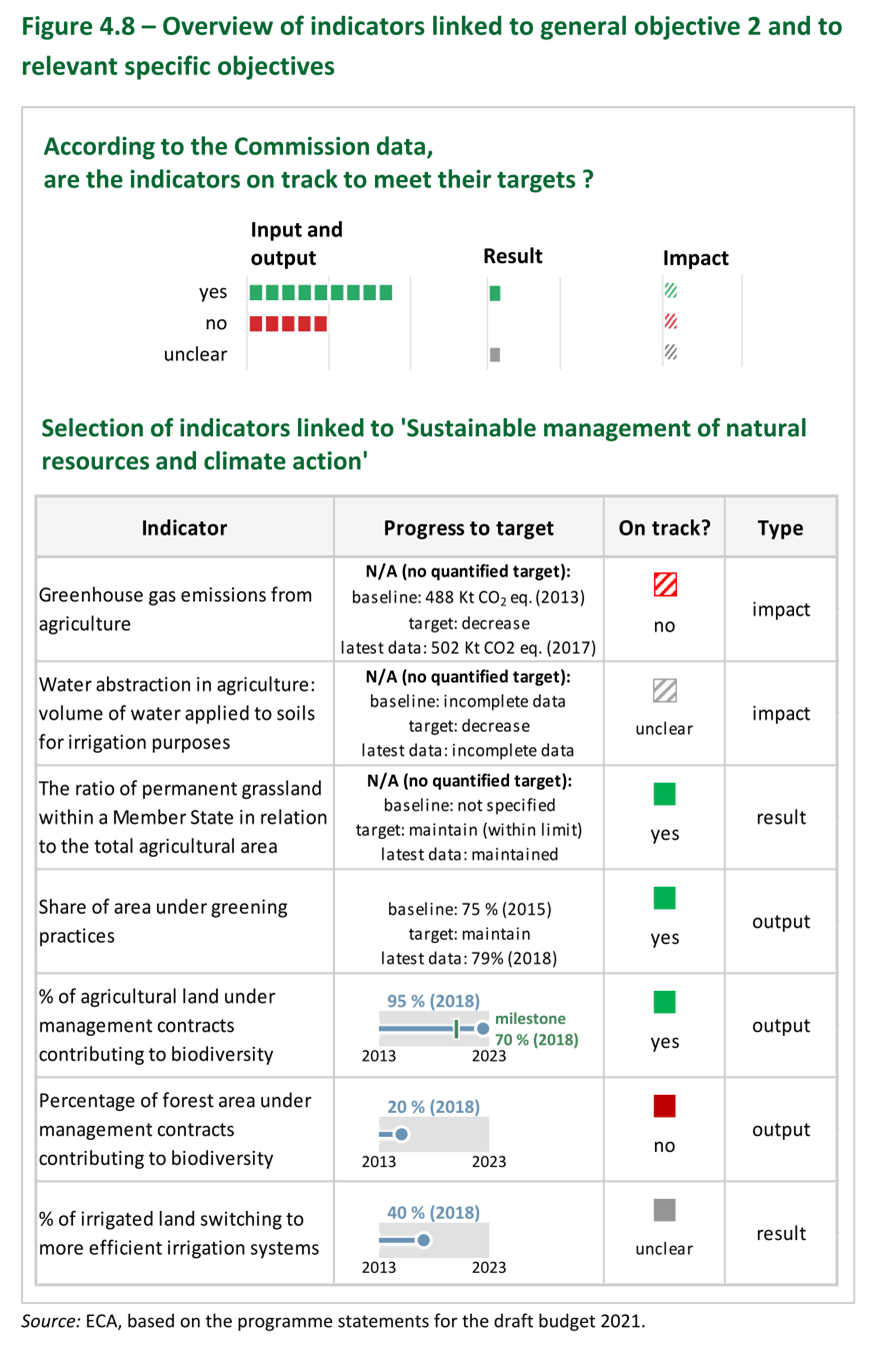

Objective 2: Sustainable management of natural resources and climate action

Sustainable management of natural resources and climate action is the second objective of CAP spending. Cross-compliance, ‘greening’ payments, and a number of rural development measures contribute towards this objective.

However when it comes to climate change, CAP is something of a damp squib. What’s more the indicators focus too much on areas of land in receipt of supports – and not enough on what the supports have actually achieved.

On greening the Commission considers it’s doing pretty well, with 79% of EU farmland subject to at least one greening obligation in 2018. In reality though the impact of greening on farming practices and the environment is questionable, the auditors point out. Greening remains essentially an income-support scheme.

Member States set their own “Good agricultural and environmental condition of land” (GAEC) standards, which are part of cross-compliance. This makes for a rather un-level playing field when standards and conditions for compliance vary to such an extent.

Grassland not always greener

Data on permanent grassland is gathered from farmers as part of their obligations under greening. Member States are expected to maintain a 5% ratio of permanent grassland or pasture – primarily for the purpose of carbon sequestration. However if it is ploughed and reseeded, grassland has lower environmental value and can actually give rise to increased CO2 emissions.

Despite this, ploughing of permanent grassland may be permitted by Member States. There is insufficient data to show that permanent grassland has not been ploughed. Among a sample of 65 farmers surveyed by the auditors, one in 10 ploughed and reseeded grassland every year.

Greening and cross-compliance are compulsory measures, but they are too weak. Member States have no means to compel farmers to take action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from livestock and crop management.

CAP is simply not designed to address climate needs, conclude the auditors, noting that the Commission in its own assessment has acknowledged the need for a more effective and targeted CAP to contribute to the environment and climate objective. Without a specific roadmap for reducing emissions in EU agriculture, the Commission’s target for a 55% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 is little more than wishful thinking.

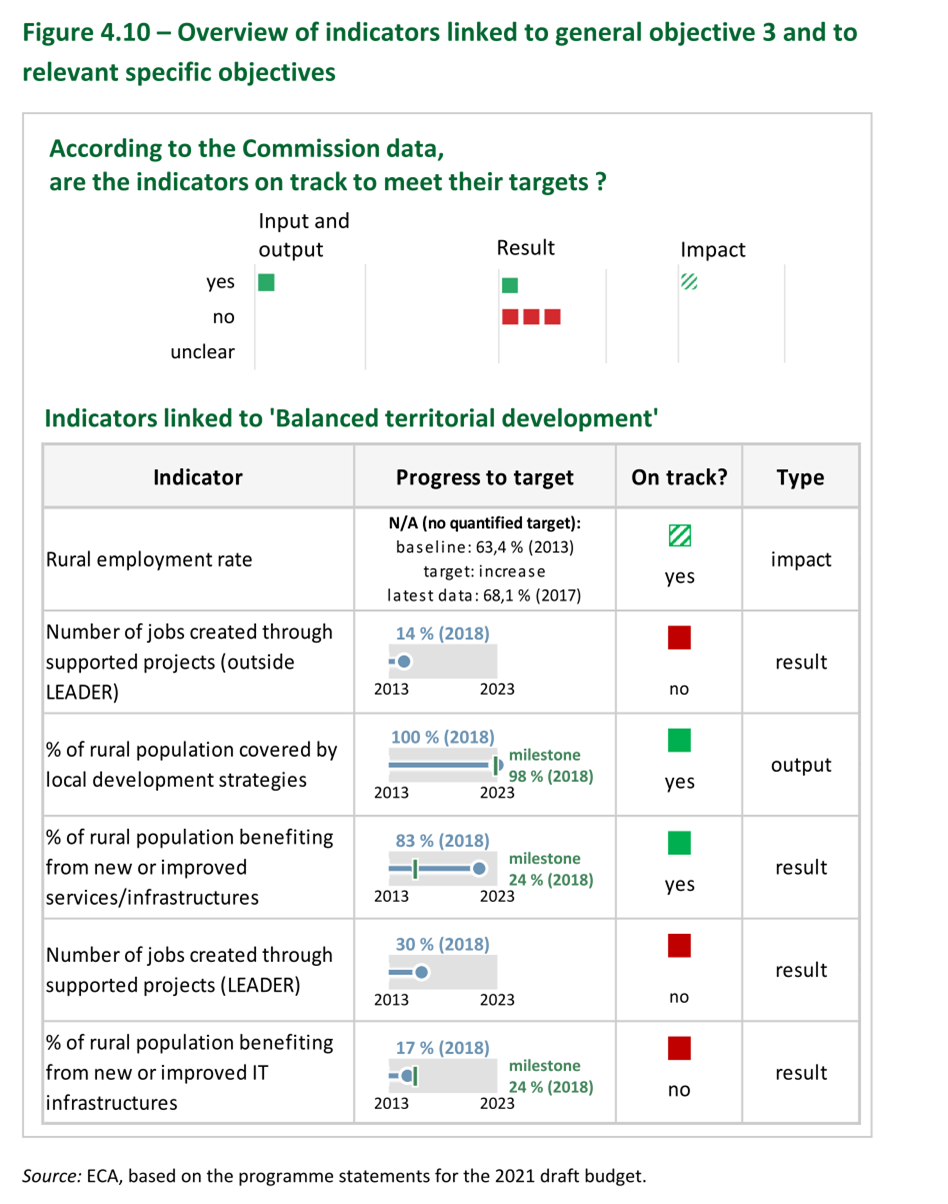

Objective 3: Balanced territorial development

Objective 3: Balanced territorial development

Balanced territorial development is the third objective of CAP spending and funded by a number of measures, including farm and business development, local development and support for developing basic services and communication technologies in rural areas. Due to the lack of available data, the auditors failed to draw any major conclusions on CAP performance in this category.

Generational renewal

New entrants can receive additional direct payments under the EAGF and one-off support from the EAFRD to set up their first agricultural holding. EAGF support for young farmers has little to no impact, while the more targeted EAFRD support is more effective; here the auditors come to the same conclusion as the Commission.

CAP generational renewal measures must be coordinated with national, regional and local policies to deliver more effective support to young farmers.

Rural jobs

CAP has little impact on rural jobs according to the Commission’s 2019 evaluation. Once again though there is a lack of reliable data.

Some indicators are simply misleading. For instance the indicators for the percentage of the rural population that benefits from improvements in infrastructure (see figure 4.10 above). As was previously flagged by the auditors (in a 2015 review of the 2007-2013 CAP) Member States can report the entire population of a municipality irrespective of how many users actually reap the benefits.

Performance testing

Within the Common Monitoring and Evaluation Framework (CMEF), 42 projects lacked a useful indicator. In some cases to remedy this Member States applied their own indicators.

The auditors highlight a results-based approach used in Poland. For investment measure 4.1 – ‘Support to improve the overall performance and sustainability of an agricultural holding’, Polish farmers are required to deliver both output and results. For example, an output could be the purchase of agricultural machinery, while “results” means an increase in the annual production/turnover of their holding.

Conclusions

In addition to indicators, the auditors recommend using evaluation as a tool to provide greater insight into the performance and policy of CAP spending. Here they make reference to recent evaluation support studies on the general objectives of viable food production and sustainable natural resources and climate action, and the ongoing evaluation of the general objective of balanced territorial development. Of course many of the conclusions in the evaluation support studies are tentative.

The Commission is required to prepare a summary report of the main conclusions of ex post evaluations of the EAFRD for 2014-2020 by December 2026 or December 2027, depending on the transitional period. By the time this data becomes available it should already have made its legislative proposals for the post-2027 period. In the meantime, the Commission can’t wait another seven years to get real on CAP spending.

More on CAP

CAP Performance Monitoring and Evaluation Framework – EP Position

Withdraw the CAP to Safeguard European Green Deal – 27 Organisations

CAP Reform | So Far Not A Game Changer For Young Farmers, Says CEJA

A Rural Proofed CAP post 2020? – Analysis of the European Parliament’s Position

CAP Beyond the EU: The Case of Honduran Banana Supply Chains

CAP | Parliament’s Political Groups Make Moves as Committee System Breaks Down

CAP & the Global South: National Strategic Plans – a Step Backwards?

CAP Strategic Plans on Climate, Environment – Ever Decreasing Circles

European Green Deal | Revving Up For CAP Reform, Or More Hot Air?

Climate and environmentally ambitious CAP Strategic Plans: Based on what exactly?

How Transparent and Inclusive is the Design Process of the National CAP Strategic Plans?