In the aftermath of the European Parliament’s adopted position agreed in October 2020, this article provides a detailed analysis of the adopted amendments in relation to the various aspects more relevant to rural development: financial allocation, flexibility between funds, LEADER, Smart Villages, environmental spending, organic farming, decentralization of delivery mechanism, etc.

The analysis reveals that the European Parliament tried to fill the legislative gaps contained in the Commission’s initial proposal, but still falls short of providing clarity and a serious EU response to more systematic rural issues. The article urges the co-legislators to look beyond the agricultural sector when negotiating in the final rounds and ensure a rural proofed CAP post 2020.

CAP reform at EU level: State of Play

On Friday 23 October 2020, the European Parliament adopted its final positions on the various parts of the European Commission’s 2018 legislative proposal for the CAP reform post-2020, namely:

- Regulation establishing rules on CAP Strategic Plans

- Horizontal regulation establishing rules on financing, management and monitoring the CAP

- Regulation establishing rules on Common Market Organisation for agricultural products.

After two and a half years of negotiations on these three pieces of legislation, the Council also adopted its position on Wednesday 21 October 2020.

In the coming months, the Council and European Parliament will negotiate their own positions to reach an agreement in the trilogues, unless the Commission withdraws its initial proposal.

In the background, the trilogues on CAP will continue in parallel with the negotiations on the Multi-Financial Framework 2021 – 2027 and the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. To some extent, these factors can still influence the results of the CAP reform and its rural development pillar.

A rural screening of the European Parliament’s position on the CAP post 2020

This article analyses the European Parliament’s adopted text on the CAP Strategic Plan Regulation, particularly in relation to rural development aspects.

This ‘rural screening’ aims to check whether the European Parliament’s position has strengthened or weakened the rural development policy within and outside the CAP Strategic Plan Regulation (e.g. synergies and coherence with Cohesion Funds).

More in detail, the analysis checks whether the European Parliament sufficiently covered some legislative gaps or maintained some of elements in the Commission’s proposal which are important for the design and delivery of rural development interventions following a territorial approach.

After assessing the most relevant amendments adopted by the European Parliament, the article draws some conclusions and suggests recommendations directed to the co-legislators involved in the last rounds of the trilogue negotiations.

Strengthening Rural Development within the CAP

Application of the principle of equal treatment and gender equality

Amendment 125 introduces the ‘integration of a gender perspective’ in Article 9 General Principles.

In the same spirit, Amendment 10 and 19 to recitals add a legal background regarding ‘gender equality’. Accordingly, the Commission should check how the Member States ensure the application of Directive 2010/41/EU in the CAP Strategic Plans.

Considering the current experience in the CAP and Rural Development Programmes, it remains unclear how this will be translated in a concrete and effective manner, and whether these points will be checked in the approval of the CAP Strategic Plans. Hopefully, these provisions will ensure no discrimination whatsoever on both sexual and gender grounds, at least in the CAP delivery.

Article 5 General Objectives

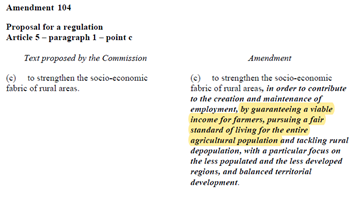

The CAP post 2020 pursues three general objectives: the last one is relevant for the rural development.

Narrowing rural development down or tightening it up to agriculture and farmers’ income is certainly a debatable position taken in the last vote of the European Parliament, especially because guaranteeing viable farm income is a need already addressed in the first general CAP objective. As recoupled in other amendments voted mainly by the major conservative parties of the European Parliament (i.e. EPP, RE, S&D), this amendment represents the usual claw back reclaiming rural development money for agriculture and farmers.

It is important to remember that although they play a crucial role, farmers are not the sole actors to be mentioned when it comes to rural development. A whole range of actors and institutions need to be mobilized and supported and their networking needs to be properly funded.

Despite the number of studies and public consultations showing that rural areas’ problems are more systematic and require a territorial (rather than sectorial) approach, the amendments assessed in this analysis clearly demonstrate a return to ‘agriculture first’ in the EU rural development policy. If the Parliament and Council adopt these amendments now, what is the relevance of the Commission’s public consultation on the Long-Term Vision for Rural Areas when it comes to shaping rural development policy for the next seven years?

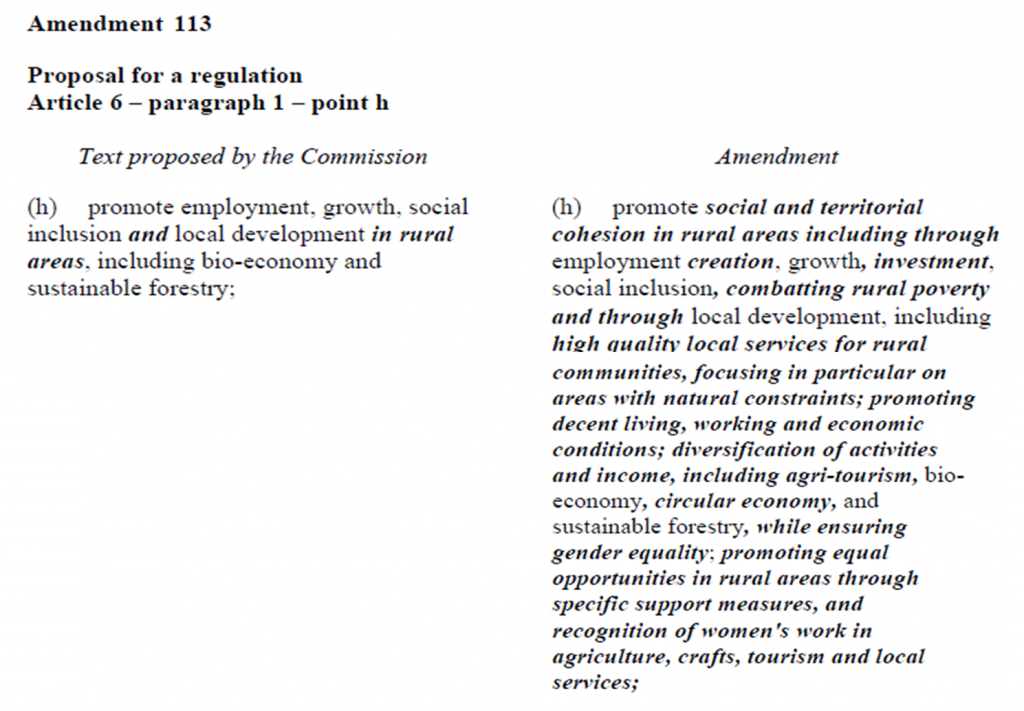

Article 6 Specific Objectives

With Amendment 113, the European Parliament adopted a more comprehensive and detailed position on the CAP specific objective (h), which is the one more related to rural development.

In the proposed additions, however, specific references to other important tools are missing. One example is social farming. It is argued here that social farming has been largely overlooked in many CAP interventions (e.g. interventions supporting Cooperation, Investments, AKIS), despite its highly needed and proved contribution to foster social inclusion in agriculture and rural areas.

While forgetting to add any reference to social farming, the EPP, S&D, and RE have followed the suggestions of high-tech, large farm corporation and machinery lobbies to add more provisions for precision farming, even by sinking money from the EAFRD budget (see the section on the amendments related to Investments and Smart Villages Strategies).

In any case, the risk of turning this specific objective into a long wish list is already very high. Its definition, however, frames the choice and features of each intervention, so much so that many elements are poorly addressed in the CAP Strategic Plan Regulation: e.g. social farming, urban-rural mobility infrastructure, digital connectivity, digital human capital and cooperation for a sustainable digitalisation of rural areas.

Article 13 Farm Advisory Services

Amendment 1129 establishes that a minimum share of 30 % of the budget allocated to farm advisory services shall contribute to the CAP specific objectives related to climate mitigation and adaptation, energy and resource efficiency, and biodiversity.

Moreover, it establishes that Member States shall ensure that farm advisory services are equipped to provide advice on both production and the provision of public goods.

While moving Farm Advisory Services towards the provision of public goods is a laudable initiative, it is important to bear in mind that Farm Advisory Services are funded by EAFRD budget for rural development. These amendments set better aims for Farm Advisory Services, but still narrow EAFRD budget down to farmers (=farm advisory services).

Farm Advisory Services for public goods are important for a sustainable agriculture. The question is why are they not ringfenced also under EAGF allocation (e.g. in operational programmes under sectorial type of interventions, or for helping the adoption of ecoschemes like agroecology or organic farming)?

Farmers and public authorities need Pillar I budget to build a functioning public advisory system and ensure access to timely, regular and independent advice and agri-environmental health checks: e.g. monitoring soil quality, water quality, disease control, weather and climate counselling, animal health.

In many parts of the EU, for instance, soil quality monitoring does not happen in any substantial way. On the contrary, in countries like Austria, publicly funded soil monitoring has been common practice for many years. The State has built a data system which monitors soil parameters at farm level, like soil organic matter or erosion by water. This should be the basis for providing independent farm advice, but also monitoring and evaluating the CAP.

Finally, no amendments have been added to clarify who are the beneficiaries of farm advisory services: the farmers or advisors, or both? The final choice seems to be left to the Member States in the CAP Strategic Plans.

Article 28 Eco- and Boost schemes

With Amendment 1130, the European Parliament introduced the possibility to support animal welfare under ecoschemes (Pillar I). In the current programming period 2014-2020, this was possible only under Rural Development measures (e.g. M14 Payment for Animal Welfare). Pillar I support to animal welfare (i.e. under ecoschemes) might be positive, but also very risky as it can represent another form of support to industrial livestock. Therefore, any claims to a greener and more compassionate CAP will depend on higher environmental and animal welfare conditionalities set up in the ecoschemes.

Amendment 1131 stresses that ecoschemes shall be different from, or complementary to Agri-Environmental and Climate Management commitments (AECM commitments) under Pillar II (i.e. Article 65). Amendment 1132 stresses that the national list of ecoschemes shall consider regional needs and be subject to bi-annual assessments from the Commission. Member States like Italy, France or Spain will have to be very smart and collaborative with the regional authorities to identify and meet the regional needs through Pillar I interventions (i.e. animal welfare under ecoschemes), which most likely will be managed centrally at national level.

‘Boost schemes’ are among the novelties introduced by the compromise amendments voted by EPP, S&D, RE. In these schemes: “Member States shall support active farmers who make commitments to expenditure beneficial for boosting agricultural competitiveness of the farmer” (Amendment 238).It is hard to understand what is expected here and how it relates to other interventions.

The same amendment specifies that ‘boost schemes’ shall be consistent with many rural development interventions, namely Investments (Art 68), Installation of young farmers and business start-ups (Art 69), Risk management tools (Art. 70), Cooperation (Art. 71), and Knowledge exchange and information (Art. 72). Maybe, boost schemes were introduced to ensure Pillar II interventions are channelled towards farmers, rather than creating a new type intervention under Pillar I. Rather than an innovation in Pillar I, this reflects the usual ‘don’t steal farmers money’ position of COPA, machinery, land lobbies, and agricultural ministries towards the EAFRD and rural development policy.

Article 64 Rural Development Interventions

As voted already in 2019 (before the last EU elections), the European Parliament adopted a few changes to the initial list of the types of rural development interventions proposed by the Commission. The main changes relate to the terminology for the environmental, climate, and other management commitments, which are now called ‘Agri-environmental sustainability, climate mitigation and adaptation measures and other management commitments’.

A similar terminological change has been proposed to the interventions for the ‘installation of young farmers, new farmers, and sustainable rural business start-up and development’. This amendment might have positive implications if it opens the possibility to support not only new start-ups, but also existing rural business (i.e. with the term ‘development’).

Furthermore, various amendments have been voted here to introduce an intervention supporting the ‘installation of digital technologies’. In this case, however, the difference with other investments (Article 68) remains unclear. Moreover, the final beneficiary of the ‘installation of digital technologies’ needs to be better defined.

Besides the actual installation of digital technologies at individual level, much more could have been done to foster a sustainable design, access, and use of digital technologies in rural areas. Moreover, the position voted by the Parliament lacks a serious EU strategy to achieve the European Green Deal target of ‘completing fast broadband internet access in rural areas reach’, as highlighted in the Commission SWD on the links between the CAP and the Green Deal (pag. 11). The lack of integration between the CAP and the Green Deal can be found also in the rural development interventions, not only in the overall level of environmental ambition.

Article 65 Environmental, Climate and other Management Commitments

Compared to the Commission’s initial legislative proposal for Article 65, Amendment 1133 establishes that payments can be granted also for the protection and improvement of genetic resources, and animal health and welfare.

In this same amendment, the European Parliament introduced the possibility to provide financial incentives on top of the payment to compensate beneficiaries for costs incurred and income foregone resulting from these commitments.

Moreover, the amendment allows Member States to vary the level of payments according to the level of ambition of sustainability in each commitment or set of commitments. As any ambition, it will all depend on where the baseline is set out. Besides this additional flexibility in setting up the paymenents, Member States will continue to decide on whether to deliver AECM payments based on commitments vs based on results, or a combination of both.

New Section: Organic Farming

Amendment 811 introduces a new section in the CAP Strategic Plans Regulation. This amendment establishes that Member States shall assess the level of support needed for agricultural land managed under organic certification. The relevance of this amendment is questionable, considering that the three major EP political groups (EPP, S&D, RE) rejected any serious commitments to integrate the CAP with the Farm to Fork and Biodiversity strategy targets, including those for organic farming. It is also narrowed to land and does not include livestock.

Anyway, the amendment establishes that, to increase the share of organic land, the “Member States shall determine the appropriate level of support towards organic conversion and maintenance through rural development measures in Article 65”. Full stop.

The amendment does not mention eco-schemes under Pillar I. Annual payments under ecoschemes can indeed support the maintenance of existing land (and livestock) under organic farming. The positive effect of ecoschemes on conversion to organic farming should not be neglected, especially if the Member States commit to providing more stable support to environmentally friendly farming practices in the long run. Therefore, it would be wise to include or, at least, recall to ecoschemes under Pillar I in this new section.

Article 68 Investments

Amendment 1139 establishes that investments under EAFRD support shall be subject to an ex ante environmental assessment. This is to avoid the situation whereby investment projects likely to have negative effects on the environment are supported.

It would be curious to see how this amendment will work and be translated in practice, considering that in many Rural Development Programmes 2014 – 2020, investments were supported to increase livestock size and intensity. Most likely, this amendment will be dumped in the trilogues negotiations with the Council, under the counterargument of ‘high administrative burden and we need more simplification’.

The same amendment determines that investments in the forestry sector will need to include the requirement of planting species adapted to the local ecosystems, or equivalent instruments in the case of forestry holdings above a certain size. But which size? Economic size or surface? This needs to be defined.

30% of the budget allocated to investments shall be dedicated to the environment and climate objectives, and higher priority shall be given to investments made by young farmers.

When complementary with other Union instruments, rural development investments can also be used to support broadband infrastructure. With the vagueness of ‘complementary’, this amendment is interesting because, so far, there has not been serious commitment from DG AGRI to dedicate CAP budget for the full coverage of high-speed connectivity in rural areas. Nor does there seem to be strong will among the Directorate Generals to increase coherence between the CAP and other funds under the Cohesion Policy.

Rural areas could be penalised by the confusion around which European fund should lead the support for guaranteeing full high-speed coverage in rural areas.

Under Article 68, a new text has been adopted by the Parliament concerning investments in irrigation, both in irrigated and drained areas. These investments were already supported in the Rural Development Programmes 2014 – 2020. This is an important amendment and shall direct investments under Art 68 towards water savings. It will be important to follow up on this amendment as it might be, as it were, watered down in the trialogue negotiations, or ineffectively implemented on the ground.

Water problems are often more systemic than technical (e.g. market oriented and intensive agriculture), and investments to increase savings from water use (i.e. at farm level) should be complemented by those aimed at savings from water abstraction (i.e. reducing the loss of water along the delivery pipelines until the farm).

Amendment 1168 establishes that Member States may grant support for the installation of digital technologies in rural areas. In this amendment, the installation of digital technologies can be granted to Smart Villages rural enterprises, but also to support precision farming or ICT infrastructure at farm level.

As in many other amendments, the three major EP political groups created a loophole to use EAFRD budget to support agriculture, precisely precision farming. As things stand, in addition to investments (Article 68), precision farming can absorb support also from ‘boost schemes’, ‘ecoschemes’, and many other interventions under EAFRD (e.g. cooperation, farm advisory, AKIS).

Article 69 Installation of young farmers and rural business start-up

Amendment 477 extends the scope of this intervention also to include ‘new farmers’ and ‘sustainable rural business development’. It is unclear whether business development can be assumed as also providing support to existing businesses. In that case, this amendment can be considered positive, as grants could be guaranteed to new businesses, but also to those already operating in the territory for many years.

The same amendment determines that any support ‘shall be conditional on the presentation of a business plan’. The amendment also includes support to farm diversification of agricultural activities, thus ensuring that grants are used to integrate agriculture into the wider rural economy and society.

In relation to ‘non-agricultural activities in rural areas being part of local development strategies’, Amendment 482 specifies that grants shall be given to farmers diversifying their activities, but also to micro-enterprises and natural persons in rural areas. While for farmers, the major political groups were disinterested about putting conditions in terms of farm economic, this amendment adds some (unclear) conditions about the size of rural enterprise (i.e. it must be micro). This might prevent support to small-medium rural enterprises. At the same time, the amendment does not prevent large farm beneficiaries of Pillar I also absorbing funds from EAFRD budget size (e.g. a large beneficiary farm from Pillar I or a large intensive livestock corporation like Friesland Campina can thus receive EAFRD support for their corporate social responsibility).

Amendment 483 defends young and new farmers’ access to EAFRD budget under this article, even if they belong to, and benefit from Pillar I market support to producer organisations.

Finally, it can be noted that for business plans requiring the collective action of multiple partners like in social farming (i.e. actors from the health, education, social prison services), the European Parliament did not include any provisions to encourage the Member States to combine the grants under this article with other rural development interventions (e.g. cooperation, knowledge transfer and information, investments). EPP, S&D, and RE stressed the combination of multiple interventions for ‘boost schemes’, but not for social farming.

Article 70 Risk Management Tools

With amendments 486, 1152cp1 and 1063, Member States have the flexibility to choose whether to grant support for risk management tools or not at all in their CAP Strategic Plans. Nothing new. In any case, whether mandatory or voluntary for the Member States, the target of risk management tools is narrowed and oriented towards farmers and income loss related to ‘agricultural activity’.

The definition of ‘agricultural activity’ will be given in each CAP Strategic Plan, but it will very likely be narrowed to ‘agricultural production’, as if agriculture had only a productivist dimension. It will be important to check whether this definition can also include ‘farm diversification activities linked to agriculture’ (e.g. agritourism, farm schools, social services, direct selling, farm camping).

This might be important to protect small-medium scale farms that brings people to rural areas and take higher risks in diversifying their gainful activities and provide community services. When an on-farm direct selling channel is broken by a catastrophic event, farmers face income and commercial damages (e.g. consumers changing outlets or sellers). Similar risks can be found in agritourism, farm schools, or social services, as observed during the COVID-19 pandemic for instance.

Therefore, the definition of agricultural activities will be crucial to understand if risk management tools will matter for rural development in general or be narrowed down to agricultural production. If included in the CAP Strategic Plan, it is suggested here that they target farm income losses in a broader sense, not only from agricultural production. Example of farm insurance schemes covering also farm business diversification can be found in Ireland (FBD farm insurance).

Finally, although funded by EAFRD financial allocation, these risk management tools continue to be framed for farmers, and less concerned about other types of rural enterprises which are important for the attractiveness and population of rural areas.

Article 71 Cooperation

In relation to this article, Amendments 497 and 1170cp2 extend the support for cooperation also to existing EIP AGRI Operational Group projects or Local Action Groups, and not necessarily to new ones. The same amendment specifies that cooperation projects can be funded if at least one entity is involved in agricultural production (LEADER Local Action Groups might be exempt from this requirement).

No provisions have been included to clarify the composition of Local Action Groups (balance between private and public partners) and to encourage the support for LAGs to design and carry out cooperation projects with other LAGs within the same MS, outside their own MS, or beyond the EU.

With Amendment 502 and 1170cp4, Local Action Groups may request the payment of an advance from the competent paying agency if such possibility is provided for in the strategic plan. The amount of the advances shall not exceed 50 % of the public support for the running and animation costs.

Amendment 830cp2 brings the LEADER initiative back to a strong focus on farmers and forestry holdings.

Amendments 500 and 1170cp2 establishes that cooperation support can be granted also to producer organisations and producer groups, despite all the Union financial assistance that these producer organisations can receive under Pillar I Market Support. In this case, cooperation in terms of promoting short food supply chains shall be more promoted. With amendment 501 and 830cp1, Member States shall not support interventions with negative effects for the environment. The criteria and rules to enforce point this are unclear.

Article 72 Knowledge exchange and information

Amendment 505 introduces the possibility to grant knowledge exchange and information support to agriculture, forestry, agroforestry, environmental and climate protection, rural business, smart villages, and CAP interventions. A definition of Smart Village is still missing in the legislative act.

Amendment 506 adds that support under this article might be given also to the creation of plans and studies. Unless the purpose and target use of these plans/studies are specified later in the trilogues, it is unclear how they can be useful for farmers or rural businesses, or how their lessons shall be seriously considered by the managing authorities in shaping the CAP Strategic Plans.

To these grants, Amendment 510 excludes courses of instructions or training which are part of the statutory normal education programmes or systems at secondary or higher levels. In general, the CAP is a public policy which should strengthen public institutions working for public interests, rather than emptying their capacity and room of action.

The question is whether this amendment will discourage or prevent universities or secondary schools to provide courses, trainings, and demonstrations, with or without necessarily being paid. More explanations are needed to justify the exclusion of these institutions, which are often public and equipped with labs and skills useful for knowledge exchange and information. On the contrary, their involvement should be prioritised.

Amendment 512 encourages the prioritisation of the delivery of rural development interventions in favour of rural women with a view to promote greater inclusion of women in the rural economy.

Amendment 513 introduced the development of Smart Villages Strategies. However, the amendment does not provide or adopt any description of Smart Village Strategy as for instance exists for Community-led Local Development Strategies (Article 33 of the Common Provision Regulation 1303/2013).

Without a description of ‘WHAT this strategy is composed of (targets, interventions, partners, etc.)’, ‘WHO can design and implement it (LAGs, regions)’, etc., the development of Smart Village Strategies might not be uniform and comparable across the EU, and it will also be hard for the Commission to develop technical assistance for the Member States (e.g. A Smart Village Strategy start-up kit).

In contrast, the European Parliament’s amendments provide more information on the purposes, interventions, and focus of Smart Villages Strategies. Accordingly, Smart Village Strategies can also support precision agriculture!

In terms of governance, while the amendment mentions that it is the Member State that shall develop and implement the Smart Village Strategy in the CAP Strategic Plans, it then adds that Smart Villages Strategies can be included into ‘integrated strategies of CLLD’. Does it mean that Local Action Groups shall adopt a national Smart Village Strategy, and if so, why should this not come from the bottom? Also, the governance aspects of Smart Villages can be better clarified.

While the concepts of Smart Villages might be clear for many, it is important to properly spell them out for all and in the legal acts. This might clarify the differences with (if any), but also strengthen the synergies with LEADER or CLLD strategies, and the coordination and responsibilities among funds.

Finally, the amendment makes some reference to the coordination between EAFRD and other European Structural and Investment Funds, although the CAP Strategic Plan Regulation has very weak provisions on this aspect. As will be pointed out later, the EAFRD fund is excluded from the Common Provision Regulation which regulates the EU Cohesion Policy.

Article 83 Financial allocation for types of interventions for rural development

Compared to the initial Commission proposal outlined in June 2018, the European Parliament adopted higher figures for the financial allocation to rural development interventions, by increasing the budget from EUR 78 811 million to EUR 109 000 million in current prices (amendment 533).

However, the European Parliament position on the EAFRD financial allocation will have to be negotiated with the figures agreed by the Council in July 2020, which correspond to EUR 87 441.3 million. The Council has a stronger say on the negotiation of the budget.

Moreover, it is worth noting that the European Parliament and Council’s figures on CAP are still pending the final adoption of the Multi-Financial Framework 2021 – 2027 (supposedly ending by December 2020).

Finally, the same amendment establishes that single EAFRD contribution rate shall be defined for each region (classified at NUTS 2 level) with different GDP per capita.

Article 86 Minimum and Maximum financial allocations

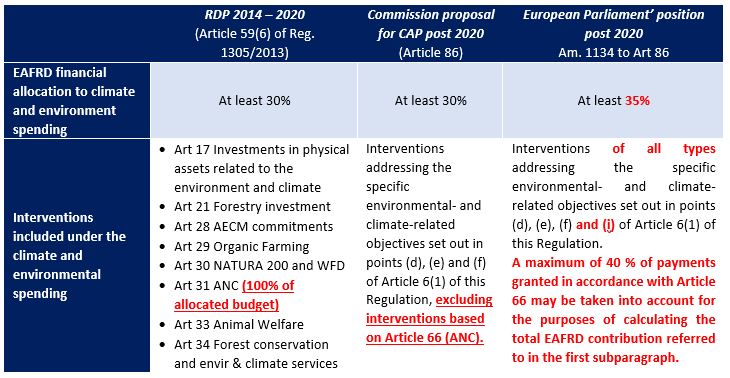

Amendment 1134 does not provide any increase of budget allocated to LEADER (5%), despite its evidenced contribution to rural development. It, however, increases the EAFRD budget ringfenced for CAP environmental objectives from 30% to 35% compared to the initial Commission proposal for post 2020 and compared to the current programming period (2014-2020).

Table 1 provides a more detailed comparison, considering also which interventions are included in this ringfenced budget.

Compared to the Commission proposal post 2020, the European Parliament’s position presents an increase in the budget for environmental spending, but continues to leave this diluted by including 40% of budget allocated to ANC. The inclusion of 40% of ANC budget under Pillar II’s environmental and climate spending goes against the Commission’s initial proposal and evidence.

For instance, as demonstrated in this report on the Status of EU protected habitats and species in Ireland, 85% of those sites are in a poor conservation state and 70% are suffering negative impacts from farming, with intensive grazing and overgrazing by livestock farmers the biggest culprit. In other countries, there continues to be a lack of evidence on the environmental assessment and data collection on the impacts of ANC payments, often justified by a Common Monitoring and Evaluation System with poor indicators.

Therefore, the inclusion of ANC payments, as well as for Animal Welfare under the environmental spending of Pillar II, continues to be controversial because of the lack of evidence showing its climate and environmental contribution, and especially because of the lack of strong conditionalities linked to this intervention.

The same amendment determines that, at least 30% of the total EAFRD contribution shall be reserved for the first three CAP specific objectives related to farm competitiveness. This includes Investments (Art 68), Risk Management tools (Art 70), Cooperation (Art 71), and Knowledge exchange and information (Art 72).

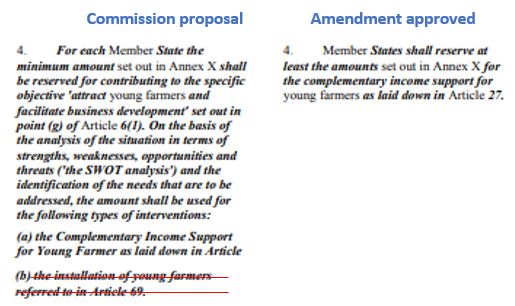

The same amendment excludes ‘rural development interventions’ (installation of young farmers and business start-up) from Annex X, which is the reserve budget set aside to contribute specifically to the CAP objective ‘attract young farmers and facilitate rural business development’.

If this amendment is adopted in the trilogues too, this means that the reserves set aside in Annex X will be confined only on ‘complementary income support for young farmers’ (i.e. Pillar I). The support for the ‘installation of young farmer and rural business start-up (Art 69)’ will be left on the shoulders of rural development interventions under EAFRD budget.

Article 90 Flexibility between direct payments and EAFRD allocations

Instead of maintaining and increasing the Commission’s proposal to transfer budget from Pillar I to II, the three major political groups voted in favour of the opposite. Transfers to EAFRD are reduced from a maximum of 15% to 12% of total allocations for direct payments (EAGF). This restricts the Member States’ room of manoeuvre to increase support for rural development.

Additionally, the spending from this transfer to EAFRD shall be conditioned towards environmental and climate interventions, which in most of the cases tend to be area-based and easy to spend (except for investments). Finally, the European Parliament voted to postpone any transfers to Pillar II from 2021 to 2023.

The same amendment specifies that the transfers to EAFRD may be deducted from basic income support for sustainability (i.e. Article 86 4(a)) or coupled income support (i.e. Article 86 4(c)), or a combination of both. This positive, but also logical, as it means that transfer to Pillar II will not come from ecoschemes (if they are adopted).

Decentralisation of the design, delivery, monitoring and evaluation of rural development interventions

With several amendments, the European Parliament stressed the regional dimension of the CAP Strategic Plans, and the importance of decentralising the governance capacity and delivery mechanism from national to regional level, particularly for rural development interventions. It is in relation to these aspects that the higher subsidiarity pledged by the CAP post 2020 might become a concrete reform.

The following amendments support the initial Commission reform aimed at simplifying and getting rid of direct interactions between the European Commission and Regional Authorities (e.g. approval of 118 RDPs, assessment of 118 Annual Implementation Reports). Nevertheless, they show how the European Parliament agreed to add provisions which could help the decentralisation of rural development interventions at regional levels.

“Taking due account of the administrative structure of the Member States, the CAP Strategic Plan should, where appropriate, include regionalised interventions for Rural Development” – Amendment 49 to Recital 55.

“Considering that flexibility should be accorded to Member States as regards the choice of delegating part of the design and implementation of the CAP Strategic Plan at regional level through Rural Development intervention programmes in line with the national framework […], it is appropriate that the CAP Strategic Plans provide a description of the interplay between national and regional interventions” – Amendment 56 to Recital 60.

“Where elements relating to rural development policy are dealt with on a regional basis, Member States should be able to establish regional managing authorities” – Amendment 57 to Recital 69. Amendment 58 to Recital 70 also adds the establishment of regional monitoring committees.

Amendment 119 to Article 7 proposes that: Member States may break down the output indicators and result indicators laid down in Annex I into more detail in relation to national and regional features in their Strategic Plans. It is still unclear if regional authorities shall also set up regional targets in relation to result indicators to be used in the performance review, as well as their role in collecting data and assessing impact indicators.

Amendment 121 to Article 8 allows Member States and Regions to pursue the CAP objectives by specifying the interventions. It is unclear if this would allow regions to design any kind of interventions, such as those under Chapter II (direct payments), III (sectorial interventions), and IV (rural development). This is a possibility, but it is hard to see it being realised.

If rural development interventions are going to continue as usual (i.e. managed and monitored at regional level), one can question whether this CAP reform has improved or created more confusion when it comes to establishing and maintaining important strategic and programme management tools (e.g. regional SWOT analysis, regional assessment of needs, regional partnership agreements, regional evaluation plans, etc.).

Strengthening Rural Development outside the CAP: synergies with Cohesion Policies

Among the novelties of this CAP reform post 2020, the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) does not form part of the new Common Provision Regulation 2021-2027 (European Parliament, 2019). This used to be the case in the current period 2014-2020.

The Common Provision Regulation (CPR) sets out common rules for shared management funds. The new CPR will cover seven funds: 1) the European Regional Development Fund, 2) the Cohesion Fund, 3) the European Social Fund Plus, 4) the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund, 5) the Asylum and Migration Fund, 6) the Internal Security Fund and 7) the Border Management and Visa Instrument.

The Commission proposal for CAP Strategic Plan Regulation has assumed that the Rural Development interventions will anyway be affected by certain articles of the CPR 2021-2027 but did not provide effective provisions to strengthen the coherence with the European Structural and Investment Funds.

Article 2(2) of the CAP Strategic Plan Regulation establishes applicable provisions from the CPR to rural development interventions. Regarding this article, it is true that the European Parliament’s position tried to stress the coherence with ESIF funds (Amendment 75). However, this amendment touches mainly upon principles like ‘sound economic governance’ (Chapter III of Title II of CPR), territorial development and CLLD (Chapter II of Title III). Much more is needed in terms of actual coordination instruments and legislative articles.

As things stand, rural development interventions and funds are not required to be part of the Partnership Agreements, which are strategic documents agreed between the Commission and the Member States to set out arrangements for using multiple funds for the EU Cohesion Policy in an effective and efficient way.

It is true that Article 98(d)(iii) of the CAP Strategic Plan Regulation establishes that Member States shall provide an overview of the coordination, demarcation, and complementarities between the EAFRD and other Union Funds active in rural areas. However, this is a provision only within the CAP Strategic Plan Regulation, rather than at interservice level (i.e. among different Directorial Generals or Managing Authorities in the Member States.

The coherence of rural policies with other cohesion funds, but also Horizon Europe, LIFE+, Erasmus, etc. is important for dealing with the most systemic issues of rural depopulation and divides with urban areas. As these issues are affected by many factors, it is important to establish provisions to ensure good governance among funds and policies.

Final reflections for the trilogues negotiations

This article carried out a rural screening of the European Parliament’s position on the CAP Strategic Plan Regulation. Overall, the analysis revealed that:

- The Commission’s proposal contained several legislative gaps for rural development (e.g. coherence with other European policies, interventions for Smart Villages, decentralisation of the design, delivery mechanism, monitoring and evaluation of rural development interventions).

- The European Parliament’s position tried to overcome these gaps; however, many adopted amendments need to be clarified and fine-tuned in detail (e.g. criteria to reject investments with negative consequences on the environment or description of Smart Village Strategies).

- In some cases, the European Parliament’s position removed important proposals of the Commission to support rural development (e.g. installation of young farmers and business start-up supported by the reserve budget in Annex X, or exclusion of ANC under environmental spending).

- The European Parliament’s position on several interventions needs to strike the right balance towards all rural potentialities, which go beyond the agricultural sector and can aim to support an integrated approach to rural development.

The Commission and the European Parliament shall team up and acknowledge the lack of EU suitable response to the rural issues: fewer local education or job opportunities/choices, difficulties in accessing public services or transport services, inadequate internet or health coverage, or a lack of cultural venues/leisure activities.

The European Parliament’s Rapporteur and Shadow Rapporteur should hold the rural voice strong during the trilogue negotiations with the Council and must not echo the old view of ‘rural as space for the agricultural sector and farmers’. This view is visible in the number of amendments and loopholes voted by the Parliament to channel rural development interventions mainly towards farmers (e.g. Smart Village Strategies supporting Precision Agriculture).

While there are apparently some steps forward compared to the current rural development programme 2014 – 2020 (e.g. higher budget for climate and environmental spending in Pillar II), each amendment should be critically analysed with existing evidence and the conditionalities linked to the spending (e.g. ANC, Animal Welfare). Any final conclusions on the level of ‘rural’ or ‘environmental’ ambition of this CAP should look at the details, as well as at the broader picture (e.g. flexibility to transfer budget to Pillar II, delegations of powers to the regions, etc.).

Finally, we urge the Commission to consider whether this CAP reform is fit for purpose or rather be withdrawn in light of its lack of integration with the European Green Deal. Meanwhile, the Commission can seek strategic alliances with other European policies and funds and address them soon in the ongoing CAP reform. Rural areas and populations count on Mr Jorge Pinto Antunes (DG AGRI, Member of the Cabinet responsible for the Long-term vision for rural areas and Smart villages/digitalisation) and Mr Roberto Berutti (DG AGRI, Member of the Cabinet responsible for Rural Development) to draw support from other funds towards rural areas, as well as to ensure that the CAP post 2020 is rural proofed.

Download this article as a PDF

This article is produced in cooperation with the

This article is produced in cooperation with the

Heinrich Böll Stiftung European Union.

More on CAP Strategic Plans

CAP Beyond the EU: The Case of Honduran Banana Supply Chains

CAP | Parliament’s Political Groups Make Moves as Committee System Breaks Down

CAP & the Global South: National Strategic Plans – a Step Backwards?

CAP Strategic Plans on Climate, Environment – Ever Decreasing Circles

European Green Deal | Revving Up For CAP Reform, Or More Hot Air?

Climate and environmentally ambitious CAP Strategic Plans: Based on what exactly?

How Transparent and Inclusive is the Design Process of the National CAP Strategic Plans?

1 Trackback / Pingback

Comments are closed.