The “Green Deal” Commission promises big spending on climate. If climate markers are to be believed, the current CAP accounts for 22% of the EU’s climate spending. The post-2020 CAP is poised to take even more climate credit. But the Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP) claims the Commission’s climate markers miss the mark. In a report released earlier this month the IEEP sounds the alarm on faulty climate accounting and greenwashing of direct payments. Far from fixing the issue, for the new CAP budget the Commission has doubled down on its flawed climate markers. The IEEP also weighs in on the climate potential of eligibility rules and conditionality. Louise Kelleher reports.

Markers that miss the mark

The European Commission pledges to plough at least 25% of the EU’s upcoming seven-year budget into climate spending. This climate mainstreaming commitment is up from 20% in the current Multiannual Financial Framework (or MFF as the budget is known in Eurospeak). Hailed as a big win for the European Green Deal, big spending on climate is meant to show the Commission is serious about tackling the climate crisis.

But how does the Commission quantify climate spending? A set of three markers are used to score each item in an EU fund – such as CAP – for the climate benefits it is expected to deliver:

- a 100% weighting indicates a “significant” potential contribution

- a 40% weighting indicates a “moderate” potential contribution

- a 0% weighting indicates an “insignificant” potential contribution

These coefficients are loosely based on the Rio markers developed by the OECD in the 1990s. The methodology was initially used by the Commission to score the climate benefits of external aid. It was rolled out across all areas of EU spending at the time of the 2014-2020 MFF, as a means to keep score of the promised 20% of the budget that was to support climate change related activities.

But these markers are based on guesswork, say IEEP researchers Faustine Bas-Defossez, Kaley Hart and David Mottershead. It’s a broad brush estimate of the potential climate benefits of this spending. The predictions are not consolidated against actual outcomes – despite the recommendations of the European Court of Auditors and others. The Commission’s climate tracking methodology fails to reflect the true impact of spending on the ground.

CAP 2014-2020: Greenwashing direct payments

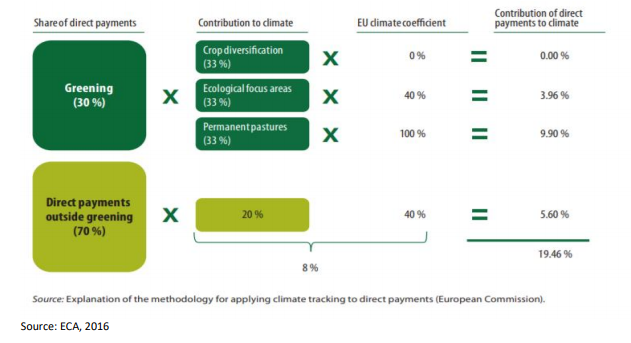

We can already see the flaws in CAP climate accounting, warn Faustine Bas-Defossez and her IEEP colleagues. The Commission has had a chance to test drive these markers in the current MFF. Below is a breakdown of how the Commission’s climate markers are applied to the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF under CAP Pillar 1):

Image 1: How climate markers are applied to the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF under CAP Pillar 1). Non-greening direct payments have an adjusted weighting of 20% x 40% i.e. 8%

Image 1: How climate markers are applied to the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF under CAP Pillar 1). Non-greening direct payments have an adjusted weighting of 20% x 40% i.e. 8%

EAGF has been credited with delivering €45.5 billion worth of climate benefits – or 22% of the MFF’s total climate spend – for the period 2014-2020. But a sizeable chunk of so-called climate expenditure is going to non-greening direct payments.

Crucially, this is at odds with the Commission’s embarrassing 2018 report on CAP and Climate, which found that the Basic Payment Scheme likely has a low impact on greenhouse gas mitigation. The same report concluded that Voluntary Coupled Support to livestock is likely to lead to a net increase in greenhouse gas emissions (although this cannot be quantified). Coupled support at least has been removed from the climate calculations for the 2021-2027 MFF.

Cross-compliance tinted glasses

How does the Commission justify crediting direct payments as climate spending? And where does the 20% coefficient come from in the above graphic? As the IEEP researchers explain, non-greening direct payments are tied to cross compliance. Only some of these cross-compliance requirements have potential climate benefits. The Commission estimates that about one-fifth of the direct payment budget will make a moderate contribution to climate change. This is why it applies the 40% marker to 20% of the total direct payments budget, giving an overall weighting of 8%. As a result 5.6% of non-greening direct payments are signed off as climate spending.

In reality little is known about the true climate impact of cross-compliance, as the European Court of Auditors has reported. Indeed lump sum payments under the Small Farmer Scheme are exempt from cross-compliance requirements, finds a 2017 study. Plus it’s hard to make a case for the climate benefits of the Statutory Management Requirements under cross compliance when these are already legal obligations.

Finally, at various stages, during extreme (and ironically climate change related) weather events, exemptions to greening rules have been granted, as we featured in 2018.

Moreover, climate-change related lump sum payments are make to farmers regularly around the Continent, often without reference to environmental impact.

How Green is Grassland?

The IEEP researchers also poked holes in the green credentials of greening payments, whose scope is limited. For example much agricultural land (16.4 million ha in 2018) is exempt from the Ecological Focus Areas (EFA).

Meanwhile “permanent” grassland is something of a misnomer. Although environmentally sensitive permanent grassland (ESPG) does deliver carbon benefits, non-ESPG permanent grassland can be ploughed and reseeded under the ‘maintenance of permanent grassland’ requirement. Permanent grassland can even move – as long as the ratio remains at least 5% of permanent grassland to total agricultural area. “Applying the 100% coefficient to the whole of the permanent grassland greening measure creates a significant overestimate of the likely climate benefits,” warn the researchers.

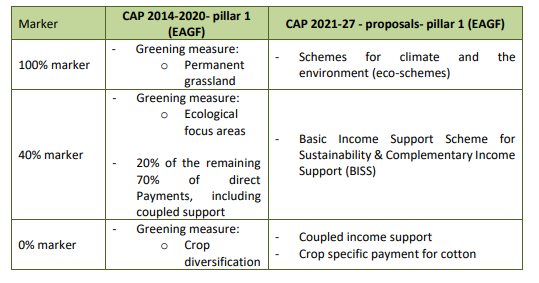

CAP 2021-2027: Doubling down on dodgy accounting

As shaky as the grounds may seem for giving climate credit to direct payments, the Commission has doubled down on this methodology for the new CAP. In the period 2021-2027 it proposes to double the weighting of direct payments from the previous 20% to a 40% coefficient. This is double the marker provided for the basic payment scheme and greening combined in 2014-2020, point out the IEEP researchers.

Below is a comparison of the weightings applied to elements of the current CAP versus the post-2020 CAP:

Image 2: Comparison of how climate markers are applied to the current and future CAP. Source: IEEP

To justify this climate upgrade, the Commission plans to roll out stricter conditions for the receipt of payments. In the post-2020 CAP, cross-compliance will be replaced with enhanced conditionality. What that means in practice is that the actual climate impact of direct payments will be largely decided by Good Agricultural and Environmental Conditions (GAEC) rules set by individual member states. The IEEP warns that at the time of writing (the report was published on February 13) these conditions were at “significant risk” of being watered down in ongoing negotiations. Thes eis evidence that this is already happening in the current CAP process, with the Council of Ministers in particular guilty of weakening the rules; while this has been the process in the previous CAP reforms. And that was before CAP emerged cap in hand from the last week’s MFF negotiations.

Race to the bottom?

Post-2020 the Basic Payment Scheme (BPS) will be rebranded the Basic Income Support Scheme (BISS). Apart from the name though, not much will change. So there’s no reason to believe these new direct payments will deliver greater climate benefits. This assumption is “at best provisional” seeing as it depends on rules that member states have yet to set, say the authors. There is a danger of a “race to the bottom” in terms of climate ambition.

If BISS is to bring climate benefits, the CAP Strategic Plans (CSP) developed by member states must be coherent and – the clue’s in the name – strategic. This means no piecemeal approval of plans. Instruments of green architecture should build on one another to optimise the impact for climate and the environment, notes the IEEP. Member States should be required to demonstrate that their GAEC standards comply with a set of climate criteria that the Commission could then use to inform its approval procedure. Promisingly, under the future CAP the Commission will need to approve all conditionality standards.

Ambitious on paper

The new proposals for conditionality look to be “a little more ambitious on paper”, note the IEEP researchers. Post-2020 there will be no more exemptions from cross-compliance or greening measures. However a not eof causiton is worth adding here, regarding the now traditional process of Ministers weakening these rules as the months drag on, as has happened before. The new ‘nutrients tool’ GAEC could bring big climate wins, but it needs to be mandatory for farmers. The new GAEC for peatland and wetland protection is also welcomed, but there is room for improvement: the definition of “appropriate protection” needs to be clarified, recommends the IEEP, and it should catalogue the types of wetland and peatland habitats to be protected.

The researchers warn against watering down GAEC. Not only should the current suite of GAEC standards be retained, it should be properly implemented and enforced in Member States. For ecological focus areas (EFAs), the focus should be on non-productive features or areas only. The authors recommend a minimum EFA share of 10% at EU level: this, while welcome, is a classic example of a measure that has been weakened in the past, both in area terms and weighting. In terms of soil cover, the Commission should provide guidance on acceptable types of soil cover.

Eligibility rules remain problematic. It’s crucial to get eligibility criteria right at legislative level as well as at the level of national and regional interpretation. These criteria should be justified by member states in their CAP Strategic Plans (CSP). In some cases eligibility rules are causing greenhouse gas emissions by inadvertently incentivising the removal of ineligible woody landscape features. The IEEP calls for guarantees from member states in their CSPs that their criteria are not incentivising the removal of woody biomass.

Definitions should also be improved. “Agricultural land” should include rewetted land that is still suitable for very low intensity production methods. In terms of carbon benefits, ploughed or reseeded grassland should not be considered “permanent grassland”.

CAP can do more for climate

Climate spending is a point of pride for the “Green Deal” Commission. It now wants to up the climate mainstreaming commitment to 27%. Parliament meanwhile is pushing for 30%, and asking how the CAP can meet the environmental ambitions set out in the Green Deal. There is a real risk of greenwashing the new CAP by overstating the climate benefits of direct payments. If spending targets are to deliver, conditionality plays a crucial role. Faustine Bas-Defossez and team at the IEEP are calling on the Commission to tighten up conditions and eligibility rules to justify the doubling of the climate weighting for income support. CAP can do much more for climate, but this faulty accounting needs to be fixed first.