How does one group of the world’s most reputable experts find that “the herbicide glyphosate is probably carcinogenic to humans”, while another group of the world’s most reputable experts finds that it is “unlikely to pose a carcinogenic hazard to humans” – in the same year?

Recently the EFSA – European Food Safety Authority – updated the toxicological profile of the herbicide.

Jose Tarazona, head of EFSA’s Pesticides Unit, said: “This has been an exhaustive process – a full assessment that has taken into account a wealth of new studies and data. By introducing an acute reference dose we are further tightening the way potential risks from glyphosate will be assessed in the future. Regarding carcinogenicity, it is unlikely that this substance is carcinogenic.”

The organisation added: “In particular, all the Member State experts but one agreed that neither the epidemiological data (i.e. on humans) nor the evidence from animal studies demonstrated causality between exposure to glyphosate and the development of cancer in humans.”

The IARC are the World Health Organisation’s cancer research agency. It found glyphosate to be a probable carcinogen.

The EFSA claim that their “evaluation considered a large body of evidence, including a number of studies not assessed by the IARC”. This is “one of the reasons for reaching different conclusions” the EFSA state.

So what are these extra studies, and where did they come from?

There is one major difference between the data sets both organisations used. The IARC state that they considered “reports that have been published or accepted for publication in the openly available scientific literature” as well as “data from governmental reports that are publicly available”.

The EFSA had access to (though did not consider all of) these. However the EFSA also considered extra studies. It considered private studies conducted on behalf of industry, which have not been through the peer review and publication process. Companies can choose to keep confidential or make available the studies they pay for.

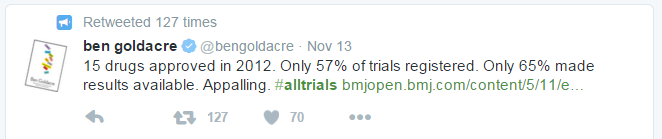

This problem with research and its availability has proven controversial. Many scientists campaign for the release of all conducted research (see #AllTrials on twitter and this example, which Ben Goldacre describes as “15 drugs approved in 2012. Only 57% of trials registered. Only 65% made results available. Appalling”).

There is something troublesome about private industry funded research. As Marion Nestle, a professor of nutrition, food studies and public health at New York University, has been at pains to point out: private studies almost never ever find against the preferences of those who fund them.

That’s in part why funders are declared on public research – the pubic and the scientific community have a right to know.

Moreover, claiming to be “exhaustive” and having a “wealth of new studies”, when a major cause of this is private industry studies – the kind the IARC would not consider anyway – is also a concern.

There are other issues with the EFSA. Both the European Parliament (in 2012, 2015) and the Ombudsman (in 2013, 2015) have admonished the organisation over its ties to the industry it regulates.

Critiquing the pace of reform at the agency, the European Parliament called the existing procedure for screening EFSA experts’ interests “subject to criticism”, and inadequate to “dispel fears about the Authority’s expert impartiality”.

Ombudsman Emily O Reilly found earlier this year that the EFSA should revise its “conflict of interest rules…for declarations of interest”. In 2013, the Ombudsman found similarly, regarding a 2008 ‘revolving doors’ case, when a Unit Head went to work for Syngenta less than two months after finishing up with the EFSA.

While one member of the 17 person IARC scientific panel was listed as an “invited specialist”, corporate watchdog organisation Corporate Europe Observatory claim “almost two thirds of EFSA’s panel scientists still have conflicts of interest and cannot be considered independent from the sector they are regulating.”

Not all groups of reputable experts then, are the same.

This article also appeared in the Irish Examiner newspaper, print edition.

More

Glyphosate: EU approval process seriously questioned

All ARC2020 articles on pesticides