Bee-killing neonicotinoid seed dressings on winter-sown cereals deliver just 2% of their active ingredients to plant tissue: there is no reliable way of assessing the environmental impact of the remaining 98%, which may be more persistent in soil and travel further in the environment than manufacturers would want people to believe.

Arable farmers in the UK were busy this autumn, when conditions were ideal for drilling winter cereal crops. The UK agricultural press has been running stories about increased plantings of winter wheat: Farmers Weekly is predicting a figure close to the record two million hectares planted in 2000.

Arable farmers in the UK were busy this autumn, when conditions were ideal for drilling winter cereal crops. The UK agricultural press has been running stories about increased plantings of winter wheat: Farmers Weekly is predicting a figure close to the record two million hectares planted in 2000.

This month sees the start of the European Union moratorium on the use of neonicotinoid products, including clothianidin, imidacloprid, thiacloprid and thiamethoxam. Does this mean that pollinators will be safer from neonicotinoids next year? It would be nice to think so, but industrial agriculture has a trick up its sleeve.

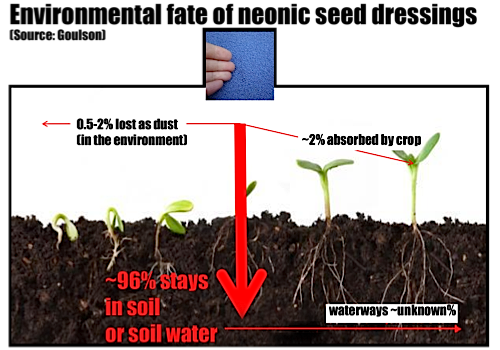

One of the common uses for neonicotinoids is a seed dressing for cereals. However, the crop only absorbs about 2% of the active ingredient from the seed dressing. Nobody knows where the remaining 98% goes, although it is probably more persistent and may travel further than some would want us to believe.

This is not a completely blank canvas: operator risk assessments were carried out for the original authorisations. As with any other finely-divided particulate, dry dust containing the active ingredient from dressed seed can blow around the fields during drilling, or anywhere else dressed seed is handled. According to pollinator expert, Dr Dave Goulson, handling dressed seed can release up to 2% of the product into the environment and this takes no account of seed that stays on the surface.

In his presentation to the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Agroecology in February Goulson explained that this phenomenon was manageable to the extent that it could be carried out when bees are not flying, but this is not the full extent of the risks posed by neonicotinoids. As the seeds grow, about 2% of the active ingredient is absorbed by the plant tissue, Goulson explains. This, too, has been closely studied and is a basic selling point for neonicotinoids.

Possibly on the grounds that there are fewer bees flying in the autumn, the European Commission moratorium explicitly exempts neonicotinoid-dressed seed for winter-sown cereal but bans it for planting between January and June, when pollinators are active. Article 14 of the preamble concludes: “Taking into consideration those risks linked with the use of treated seeds, the use and the placing on the market of seeds treated with plant protection products containing clothianidin, thiamethoxam or imidacloprid should be prohibited for seeds of crops attractive to bees and for seeds of cereals except for winter cereals and seeds used in greenhouses.”

Annex 1 opens with a paragraph that spells out a January to June closed season for dressed seeds for cereal crops: “Uses as seed treatment or soil treatment shall not be authorised for the following cereals, when such cereals are sown from January to June: barley, millet, oats, rice, rye, sorghum, triticale, wheat.”

One of the problems that has yet to be addressed with neonicotinoids, Goulson warns, is their persistence in soil. Estimates for the half life of imidacloprid range start from 200 days. Goulson points to evidence of persistence in the data published in the 2006 Draft Assessment Report for Imidacloprid.

In addition, there is a risk to water courses, depending on local hydrology. So while careful product management can account for up to 4% of the seed dressing, some 96% of the active ingredient is still lurking underground. Here, it is out of sight and out of mind until it starts to find its way back. Whoever blindsided the European Commission into the winter cereals exemption overlooked this fact. Or never thought about it.