With the UK vote to leave Europe, the government of the day would launch the formal process by invoking Article 50 of the consolidated version of the Treaty on European Union. Peter Crosskey already made some observations about Brexit, agri-food and Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty in his article in May. In the light of current events, this is a re-post of his explanations on Article 50.

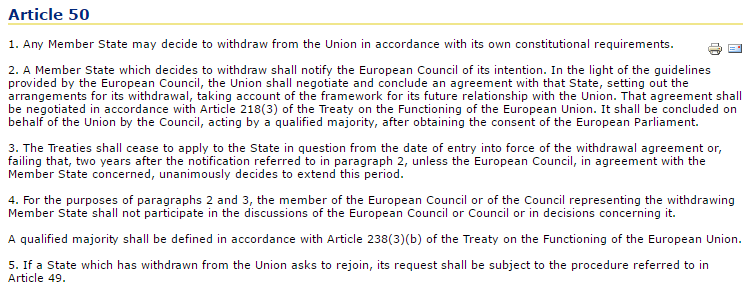

Paragraph one reads: “1. Any Member State may decide to withdraw from the Union in accordance with its own constitutional requirements.” From a Brexiteer’s viewpoint, so far, so good.

Paragraphs two and three set out the mechanisms and timetable by which such a withdrawal would be decided. Here is a key passage from paragraph two: “…the Union shall negotiate and conclude an agreement with that State, setting out the arrangements for its withdrawal, taking account of the framework for its future relationship with the Union.”

Paragraph four is a game changer that destroys any semblance of the UK’s self-determination in this process:

“4. For the purposes of paragraphs 2 and 3, the member of the European Council or of the Council representing the withdrawing Member State shall not participate in the discussions of the European Council or Council or in decisions concerning it.”

Once paragraph four is taken into account, there is no only a curtailed role for the UK government to play in discussing the terms of the settlement that will be negotiated by the 27 remaining members of the European Union. Within a two-year window the UK will have to accept whatever is handed down by the remaining member states, which will take into account: “…the framework for its future relationship with the Union.”

This is neither a new nor an original interpretation of Article 50:

- Alan Renwick of University College London’s Constitution Unit covers article 50 in some detail;

- Dr Giacomo Benedetto of the Centre for European Politics discussed Article 50 on January 3, 2016;

- Agata Gostyńska-Jakubowska of the Centre for European Reform wrote about the Seven Blunders: Why Brexit would be harder than Brexiters think on April 28 and

- December 2015, Bronwen Maddox described Article 50 as “an EU referendum horror” in Prospect Magazine.

Paragraph four of Article 50 deserves to be heard more clearly and by a wider public.

there is still of course the fact that the 27 will, in essence, form their own team (without the UK) to negotiate with the UK…ie that the UK will inevitably be left out of this part of the process.

I am grateful to Alan for the clarification and welcome his reassuring words of wisdom.

Peter is absolutely right to highlight the importance of Article 50 to the process of a UK exit from the EU. However, I think it is overstating the case to say that “there is no role for the UK government to play in discussing the terms of the settlement that will be negotiated by the 27 remaining members of the European Union.”

Professor Renwick explains the situation in the blog post that Peter quotes as follows:

“Writing in Prospect magazine last month, Bronwen Maddox said, ‘Clause 4 says that after a country has decided to leave, the other EU members will decide the terms—and the country leaving cannot be in the room in those discussions. Repeat: we’d have no say at all on the terms on which we’d deal with the EU from then on, and no opportunity to reconsider.’ That isn’t right: Clause 4 says only that we wouldn’t be in the room when the EU decides its position in the negotiations; but of course we would be in the room when the EU is negotiating with us. Furthermore, the UK is a country with clout, and it could use that to extract some advantage.”

It may be cold comfort for those of us who view the referendum outcome as the wrong decision for both the UK and the EU but, should Brexit go ahead, it does open the possibility for a settlement that would try to minimise the damage for both sides, holding out the hope that under a new generation of political leaders the UK would seek re-admission at some point in the future.