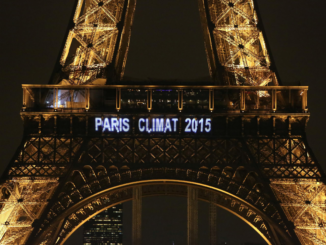

The Brazilian coffee area is one of the warmer areas on the globe in relation to what it was one hundred years ago. As Brazil makes up the largest share of the global output, and with that share of production increasing, rainfall deficits in the country due to climate change have far reaching implications for the entire global coffee market. Government officials and international negotiators might not feel this effect during coffee breaks, in a major UN climate conference taking place in Paris later this year, but with low rainfall rates in Brazil becoming more frequent and severe, the implications for coffee production internationally are not to be ignored.

According to a report released by Volcafe, the coffee trading arm of ED&F Man, one of the leading commodity merchants in the world, drought has really become new frost with widespread implications. Back in the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s, frost was really something that drove the coffee market, while drought was an afterthought. What we see nowadays is drought coming to the forefront, increasing in both duration and severity. Shifting the production area further north in Brazil played a role in this, while increasing global temperatures and shifting of weather patterns did too.

The spike observed in coffee prices in 2014, which resulted in a doubling of prices in just a few weeks, was a direct function of moisture deficit during the Brazilian winter just ahead of the harvesting season. That year, there was a 21 percent fall in initially forecasted crops, and 14 million bags of coffee were lost due to this unusual weather event. This represents nearly 10% of the global crop coming off the market, all within a matter of weeks. But, severe droughts of longer duration in a given year do not only affect annual yields: they actually impact multi-year productions, since coffee plants do not only invest energy in developing the cherries, but also for vegetative growth influencing potential yields in the following year.

The exacerbated effects of climate change on the price of a commodity of such popular demand is a call to action against climate change, one which should not only focus on adaptation, but also on mitigation of its effects. One way to stand this tide is by increasing the efficiency of the production. When farmers are able to produce in efficient ways, they are able to realise better yields and mediate production falls. Another way is by investing in risk management scenarios across the supply chain. Some government and supranational programs are trying to bring this knowledge to coffee farmers in Brazil. As a matter of fact, some sophisticated, large-scale producers are already doing this. But despite these efforts, we are nowhere close to preventing uncertainty, created in the coffee market because of drought.

According to Volcafe, what we are really fighting against is the volatility of prices. This doesn’t mean that high prices are a bad thing, but high prices create these wild swings in the market, and then volatility is a bad thing. Admittedly, coffee is one of the most volatile commodities there is anyway. But nobody that sells or buys coffee in the commercial space really likes any extra price variabilities, except maybe for speculators. Given the effects of global warming on yields, coffee is expected to continue to be an extremely volatile market.

What we can expect from climate change is that it is going to excite more extreme weather events. And if we are going to be growing coffee to meet a huge global demand, we need to be growing it in conditions of rising temperatures. All these things come of course at a cost, and this cost has to be translated further down the supply chain. This sort of volatility will inevitably add to that increased cost. In any case, with drought now a key variable to production, rainfall forecasts are going to be watched as closely as frost forecasts once were.

An Ethnobotany and Biodiversity researcher, active in the food movement of Greece, Pavlos is also a an olive grower, food author and film producer. Follow him on twitter.

1 Trackback / Pingback

Comments are closed.