The Ukrainian government currently faces a major dilemma in agricultural development: to continue supporting large-scale export-oriented agriculture or refocus on family farming. A new report by Natalia Mamonova, Olena Borodina and Brian Kuns address this uneasy dilemma in the context of Russia’s war in Ukraine. Here Mamonova provides a summary of the key points.

A new report was prepared by Natalia Mamonova (Ruralis, Norway), Olena Borodina (National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine) and Brian Kuns (Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences). They analysed Ukrainian agricultural policies during the war and the post-war recovery programs, and how these policies meet the needs of large export-oriented agribusinesses compared to small farmers in Ukraine.

Although government policies during the war generally benefit large agricultural businesses – as they had before the war – the situation is much more complex. The Ukrainian government is currently facing a major dilemma: whether to continue supporting large-scale export-oriented agriculture, which is seen by many policy makers as a way to reconstruct and rebuild the country after the war, or to refocus on the family-based farming that is socially, environmentally and economically sustainable and has to be enhanced if Ukraine wants to join the EU in the nearest future.

Below are the 9 main arguments of their report, which summarise the content. Links to the full text of the report in English and Ukrainian can be found at the end of this article.

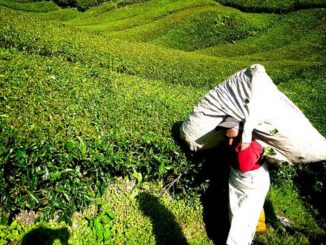

1. Agriculture is the central pillar of the Ukrainian economy.

and as such a major source of livelihood for about one third of the Ukrainian population. It contributed to 10.9% of GDP, provided 17% of domestic employment and accounted for 45% of export earnings in 2021. Ukraine is one of the world’s top agricultural exporters of grains, oilseeds and vegetable oil, playing a critical role in supplying food to food-insecure countries in Asia, Africa, the Middle East.

2. Ukrainian agriculture is characterised by the coexistence of two different types of agricultural producers.

These are large-scale industrial agribusiness and family-based farming. Agribusiness primarily specializes in the production of grains and oilseeds for export. Family-based farming is represented by a diverse set of small and medium-sized family farms and rural households that produce potatoes, vegetables, fruits, grain, dairy and meat products for personal consumption and sale in domestic markets.

3. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, has severely disrupted food production and trade in Ukraine, jeopardising Ukrainian and global food security.

While export-oriented agribusiness suffered the heaviest losses, especially at the beginning of the war, family farms and rural households were able to adapt to extreme conditions and provide food to the Ukrainian army and people. The war demonstrated the critical importance of local food systems to domestic food security

4. Emergencies benefit the big players.

Most of the agricultural policies initiated by the government of Ukraine during the first year of Russia’s war in Ukraine were an effective response to emergency circumstances and were aimed at enhancing domestic food security and solving the acute problem with storage and export of Ukrainian grain and oilseeds. However, these polices have largely been directed to the benefit of large-scale industrial agriculture instead of smaller food producers.

5. Russia invaded Ukraine in the midst of a land reform aimed at lifting a moratorium on the sale of farmland.

Proponents of continuing land reform during the war argue that an open land market will increase investment in Ukrainian agriculture and generate significant revenues to the state budget, which are needed to rebuild and reconstruct the country. Opponents propose to suspend land reform until the end of martial law. They argue that pursuing a land reform is extremely problematic when a large share of the population has been displaced, a fifth of the territory is under occupation, and family farmers and rural households are not financially strong enough to buy the land.

6. The New Agrarian Policy is one of the central pillars of Ukraine’s Recovery and Development Plan – but it too favours the big exporters.

presented at the first Ukraine’s Recovery Conference in Lugano, Switzerland in July 2022. The New Agrarian Policy largely aims at restoring the pre-war production and economic model of globalised export-oriented agriculture. By focusing on increasing production volumes, land-use efficiency and the development of new export destinations, the New Agrarian Policy does not sufficiently consider the interests of family farmers and rural households.

7. There are alternatives.

Representatives of Ukrainian academia, civil society and family farming organizations proposed alternative recommendations to the government of Ukraine with specific measures on how to rebuild Ukrainian agriculture to meet the interests of small food producers and make Ukrainian agriculture socially, environmentally, and economically sustainable. They base their recommendations on domestic practices as well as international guidelines and principles for sustainable and responsible land use and agricultural development, including the UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants, the European Green Deal, and principals of agroecology and food sovereignty.

8. EU rules may help theses alternatives.

Although the government of Ukraine is obviously leaning towards supporting large-scale industrial agribusiness, it has to revise domestic rules and regulations to comply with the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy and other EU norms and regulations due to Ukraine’s commitment to join the EU. This should in theory imply less support for large-scale export-oriented agribusiness and more investment in commercial family farming and rural development programs.

9. EU member states with big agri-sectors may fear Ukraine in the EU.

The European Union and international organisations have proven to be reliable allies of Ukraine in addressing the problem of Ukrainian food exports, as well as in providing financial, logistical and legislative support to Ukrainian agriculture during Russia’s war in Ukraine. However, the conflict that erupted in the EU in April-September 2023 due to the presence of Ukrainian food exports in Eastern and Central European markets has demonstrated that EU member states with farmer based agrarian sectors will likely fear competition from Ukrainian agriculture, which can hamper EU-Ukraine agricultural negotiations.

Read Ukrainian agriculture in wartime – resilience, reforms, and markets

More

Food Security, Food Sovereignty, and Collective Action During the War in Ukraine

Food Security versus Sustainability in Europe during the war in Ukraine

Ukraine | the Green Road of Ecovillages – Communities that Protect