What Brexit will mean for the future of UK and EU food and farming has been the topic of much debate and much uncertainty in the past few months. As the Brexit withdrawal plan is becoming more concrete, so too are the potential opportunities and concerns for the food system. Sharon Treat from the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy (IATP) talks us through five key risks.

“Brexit”—the impending withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union triggered by the 2016 UK referendum—presents a number of significant risks to the future of sustainable food and agriculture in both the UK and the EU. Through the UK’s future trading relationships, there are also implications beyond Europe’s borders. Until now, the nature of those risks has largely been a matter of speculation. But recent actions of the UK government firming up details of its Brexit withdrawal plan, coupled with interest by both the Trump and May administrations in negotiating a “super fast” trade deal, have raised the stakes. We flag five significant risks posed by Brexit:

- Weakened food safety and labelling provisions;

- Inadequate environmental protections, especially from agricultural pollutants;

- Risks to strong animal welfare protections and biotech regulations;

- Negative impacts from border and mobility restrictions; and

- The overarching impact of new trade deals that could extend the reach of these risks beyond the UK to the EU or across the Atlantic.

In early July, Prime Minister Theresa May and her cabinet announced their agreed-upon vision for the future of the UK after Brexit. The three-page “Chequers Agreement” was soon followed by a 104-page white paper outlining the government’s blueprint for the future relationship between the UK and EU, and the extent to which existing laws and regulations, including the tariff-free single market and customs union, would continue to apply to the UK. After weathering resignations by key cabinet members who opposed what in their view was a Brexit vision that was too “soft”—that is, still linked too closely to the EU – May’s government succeeded in enacting its EU withdrawal bill, which became law on July 26. That law repeals the 1972 European Communities Act, which took Britain into the EU, and provides the framework for UK governance after Brexit. To provide legal continuity, it will enable existing EU law to be moved into UK law, at least temporarily. The final scope of what is retained from EU laws and the extent to which the UK remains linked to EU laws, regulations and judicial rulings in the future is central to the debate still being played out within May’s Cabinet and her Conservative Party, in Parliament and across society.

The Brexit clock is ticking. Only eight months remain before the March 29, 2019, exit date agreed to by May’s government and the European Commission in the draft withdrawal agreement, to be followed by a transitional implementation period ending on December 31, 2020. A so-called “hard” Brexit, without any agreement with the EU, is still a possibility that both May’s government and the European Commission are warning about, in large part because the key issue of the Northern Ireland border remains in limbo.

The no-deal outcome poses the greatest long term risk to food safety and in the short term, could threaten food supplies and cause significant disruption of the economy. Although the Brexit strategy outlined in May’s white paper is facing skepticism from the EU’s top negotiator on several grounds, including the viability of its agri-food proposals, it remains the best guidance available, along with the amended EU withdrawal law, to the UK’s future. With that in mind, we dig into its substance to flag five significant Brexit concerns not only for farmers and consumers in the UK and the EU, but ultimately globally as industrialized agriculture further expands its reach.

1. Weaker food safety and labelling rules

The May government’s proposal on agriculture and food policy has significant loopholes that threaten food safety and consumer protections. The white paper envisions a free trade zone for goods, with “a common rulebook for agriculture, food and fisheries products, encompassing rules that must be checked at the border, alongside equivalence for certain other rules, such as wider food policy,” (Chapter 1, para 12.d).

This sounds good, seemingly promising adherence to EU food and agricultural standards, but the promise is undercut by the intention that the food safety “common rulebook” applies only insofar as needed to avoid checks at the border (“frictionless border”) and excludes other policy affecting food. Only “relevant” Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) protections would be within the common rulebook, (white paper at Chapter 1, para 34.a). Environmental, agricultural and consumer rules, including food labelling requirements and limits on pesticide residue levels, as well as enforcement mechanisms, would not be covered by EU rules.

The white paper explains the labelling rationale thusly: “It is not necessary to check these rules are met at the border, because they do not govern the way in which products are produced, but instead determine how they are presented to consumers. These rules are most effectively enforced on the market and as such it is not necessary to incorporate them into the common rulebook.”

Others would argue, IATP among them, that labelling requirements—whether identifying country of origin, genetic engineered content, ingredients including additives, freshness, and/or nutrition – lie at the heart of effective food policy. The EU has extensive food labelling requirements that, under the scenario laid out by May’s government, could go by the wayside in a post-Brexit UK. Not only will this limit consumers’ access to information about their food and undermine food standards in the UK, but non-compliance with EU labelling requirements would likely undercut EU consumers’ trust that post-Brexit UK food imports meet high EU standards.

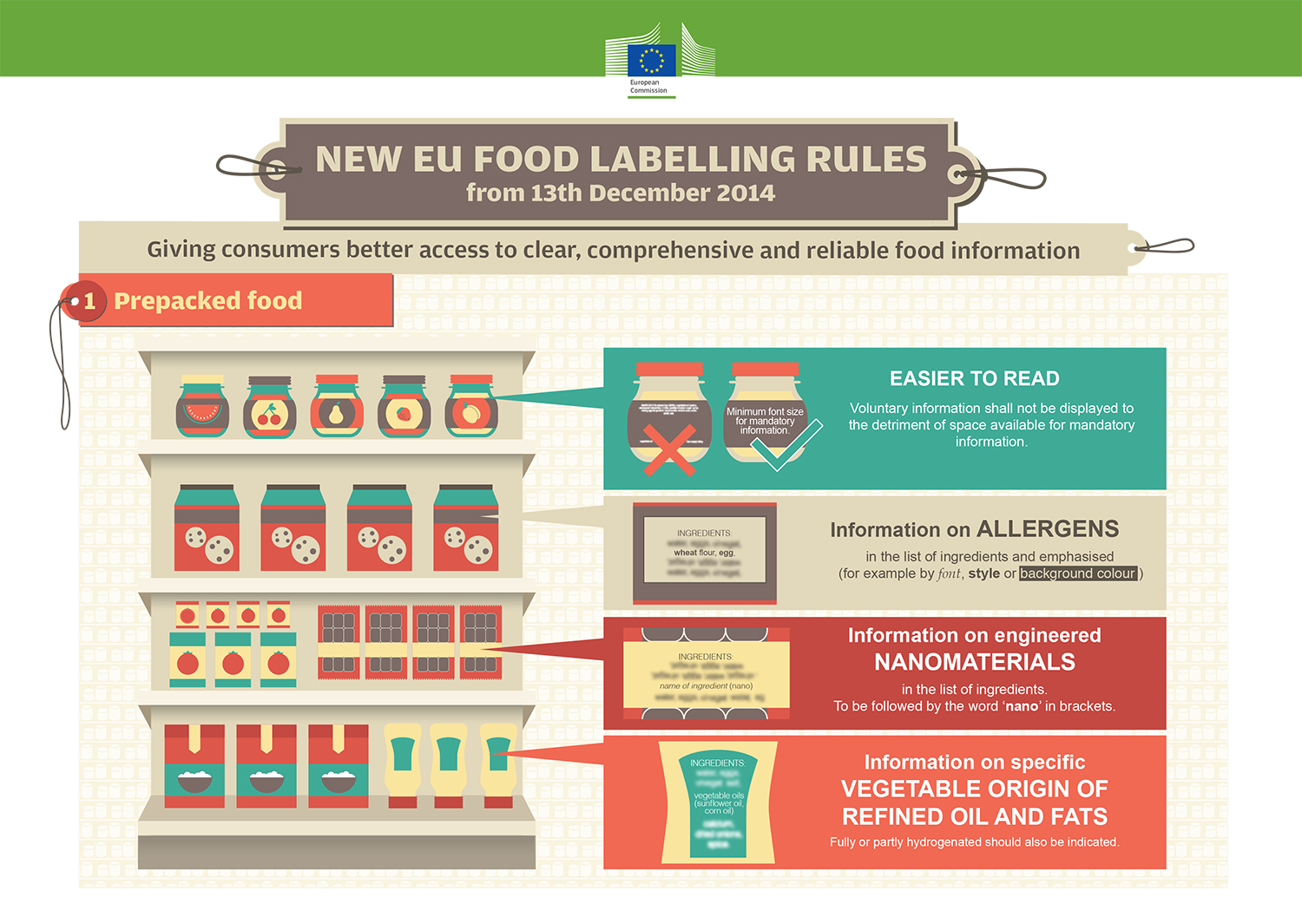

This EU government infographic for consumers shows just what could be lost, including

- Legibility of information (minimum font size for mandatory information)

- Mandatory allergen information

- Mandatory origin information for fresh meat from pigs, sheep, goats and poultry

- List of engineered nanomaterials in the ingredients

- Specific information on the vegetable origin of refined oils and fats

- Indication of substitute ingredient for ‘imitation’ foods

- Clear indication of “formed meat” or “formed fish”

- Clear indication of defrosted products

View the European Commission’s food labelling rules 2-5.

Some of these requirements, indeed, address safety concerns-for example, noncompliance with allergen warnings could lead to serious health consequences or even death. In fact, recent UK food recalls due to noncompliance with EU food standards included “several products which contained allergens, including sulphur dioxide and/or sulphites, not correctly mentioned on the label.”

Needless to say, several of the EU’s labelling requirements (including disclosure of nano and GMO ingredients and identifying country of origin) don’t even exist in the United States, with which the UK is aiming to quickly enter into a comprehensive trade agreement. This circumstance creates strong pressure on the UK to abandon the EU requirements. In the case of SPS rules proposed to be within the common rulebook, it is unclear how these rules would apply to third parties exporting to the UK. If third countries are free to enter into trade deals based on their own standards, there will be significant risks not only to UK consumers, but also to EU consumers who could see unlabeled foods potentially transshipped or processed in the UK from countries such as the U.S. that do not meet EU food standards.

May’s proposal to place agricultural and environmental policy outside the common rulebook has significant implications not only for the environment and animal welfare, as we discuss later, but also for food safety. In just one example, if as proposed, pesticide rules are outside the common rulebook, food would not be required to meet the EU’s maximum residue levels (MRLs) limiting consumer exposure to toxic pesticides. This will affect consumers in both UK and EU, the latter of whom would be consuming UK-grown produce shipped through a “frictionless border” without further safety checks. Under this scenario, how could the EU guarantee that UK-produced foods will meet EU standards? Once again, this is a policy area where the U.S. (and other countries outside the EU) permit residue levels that are often higher than EU standards. The pesticide issue has already been flagged by Michael Barnier, the EU’s top Brexit negotiator, as well as by independent researchers, as a major concern. Although the white paper suggests equivalence agreements could fill in these gaps (see Chapter 1, para 37), as IATP has detailed in the context of the EU’s trade agreement with Canada, mutual recognition of equivalence often does not achieve the same level of protection. European consumers’ opposition to proposed regulatory equivalence provisions for food in the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership helped sink those negotiations.

Parts 2 and 3 will follow in the coming week.

This article was first published on the IATP website.

Sharon Anglin Treat is Senior Attorney at the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. For more than a decade, a major focus of Sharon’s policy work has included international trade agreements and their intersection with environmental, food and public health policy. Sharon first got involved in trade policy as a state legislator In Maine, which in 2004 established the Maine Citizen Trade Policy Commission to advise state and federal policymakers and to provide a forum for both educating the public and receiving feedback on the impacts of trade policy. Sharon has served on the Commission for a number of years, including several as co-chair, and represents the Commission on the Intergovernmental Policy Advisory Committee (IGPAC) to the U.S. Trade Representative. More here.