A carefully crafted narrative is framing GMOs as an essential ingredient in sustainable food systems. The Commission’s current proposals favour biotech innovations to tackle the risks posed by climate change and loss of biodiversity.

A decision to prioritise GMOs over other approaches – such as a diversity of plant genetic resources, produced and adapted locally by a diversity of players – carries a significant path dependency that will likely shape the future of our food systems for decades to come.

Could a solid reform of the seed marketing legislation provide a more effective and safer response to sustainability commitments?

Analysis by Mathieu Willard and Adèle Pautrat

Mastering the narrative: the industry in control

Biotechnologies are indispensable for achieving the sustainability goals for our food systems: this is the narrative that has been crafted by the Commission, the industry as well as some parliamentary groups such as the EPP, in their pursuit of deregulating GMOs in the EU.

Recognising the complexity of the scientific debate surrounding GMOs is essential. Forming hasty conclusions that label GMOs as either the perfect solution or a life-threatening danger is challenging and likely scientifically inaccurate. But what is for certain, is that the introduction of GMOs in EU fields would have a systemic impact on agriculture. It is not a simple solution you can introduce in a silo. It is a system defining decision.

Therefore, it is all the more frustrating to see the proposal intended to address changes in the food system (the Sustainable Food Systems law), a much needed guide, sidelined during this legislative session.

But this narrative has become dominant in the decision making sphere. Over many years, biotech corporations have leveraged their economic influence to promote positive narratives about new technologies to the public and decision-makers, such as the old promise of reduction of pesticides use.

And those false promises (based on false premises) have intensified lately, particularly in recent efforts to lobby for the deregulation of GMOs. In the stakeholder consultation held in 2020, key industry stakeholders pushed a narrative centred around the sustainability of GMOs.

COPA-COGECA’s consultation argued: “in order to address the challenges presented by climate change, tackle plant diseases and protect biodiversity, a clear solution for new breeding techniques needs to be developed at European level”.

Euroseed specified that “preventing farmers in the EU to use respective NGT plant varieties will put efforts towards more sustainable farming at risk”. On their website, Euroseed explains that they, with their partners, have been hosting “live and online events since mid-May to highlight the crucial role of plant breeding methods in developing a more sustainable agriculture”.

The last breath of an empty Farm to Fork promise?

Indeed, the EU needs a transition towards more sustainable farming and food systems. This objective is a big part of the Green Deal that dedicated a distinct strategy to that purpose: the Farm to Fork Strategy (F2F) states that seed diversity is a prerequisite for sustainable food systems.

But what is left of the F2F objectives today? While the EU managed to authorise glyphosate for 10 more years, what convincing legislations have been tabled? Where is the Sustainable Food System proposal (SFS), the Animal Welfare revision, the Pesticide Reduction or the Enhancement of Organic Farming? Inaction and empty promises remain.

With the time it has left, the Commission chose to pursue a toxic package of agrifood files: the deregulation of GMOs and a revision of seed marketing legislation which is claimed to preserve genetic diversity in farming.

But how does the Commission plan to evaluate the sustainability of GM plants, and what connection does it have with the revision of the Seed Marketing legislation? Is the ultimate objective to promote sustainable practices, or is it a set-up to allow GMOs to easily enter the European market?

Sustainability Criteria: A Gateway to GMOs?

The outcome of this meticulously crafted narrative is the establishment of flawed sustainability criteria that interconnect GMO and seed marketing legislation.

Let’s first have a look at the EU legislation on seed marketing. As a general rule, seeds must undergo registration by the national seed authority before entering the market. The current variety registration process rests on two main pillars:

- DUS – Is the variety distinct, uniform, and stable?

- VCU – Does the variety offer added value for cultivation and use?

Significant changes are anticipated in the new legislative proposal, particularly in the second pillar. VCU will be rebranded as “value for sustainable cultivation and use” (VSCU). The criteria assessed in this evaluation will now encompass new traits relevant to sustainability.

Three primary criticisms are raised regarding the shift from VCU to VSCU. The first two critiques pertain to the internal workings of the registration process.

First, while the VCU test mostly applied to cereal crop species, the VSCU will also apply to vegetables and fruits. This will strongly increase their production costs, for conventional but also organic breeders.

Second, while the DUS test must be carried out by national authorities, the VSCU tests may be conducted by the applicant itself, under official control.

The privatisation of controls is likely to result in the erosion of public services that traditionally conduct official assessments, potentially even causing their disappearance, especially in regions with limited seed company presence. This diminishing role of public inspection services could make smaller companies more reliant on a handful of large seed corporations, who will be the only ones possessing the necessary logistical resources to conduct inspections under official supervision. Ultimately, this trajectory may contribute to increased market concentration within a few dominant entities.

Finally, the third criticism focuses on the identification of a vital connection between VSCU and the forthcoming proposal for GMO deregulation. In the case of approving ‘category 2’ NGT plants, specific incentives are granted if a plant exhibits any one of the broadly defined traits outlined in Annex III of the proposed regulation. As illustrated in the table below, the attributes of Annex III closely align with the characteristics of VSCU.

| GMO deregulation (for NGT-cat.2; proposal Annex III) | Seed Marketing proposal (VSCU characteristics, article 52) |

| yield, including yield stability and yield under low-input conditions | yield, including yield stability and yield under low-input conditions |

| tolerance/resistance to biotic stresses, including plant diseases caused by nematodes, fungi, bacteria, viruses and other pests | tolerance/resistance to biotic stresses, including plant diseases caused by nematodes, fungi, bacteria, viruses, insects and other pests |

| tolerance/resistance to abiotic stresses, including those created or exacerbated by climate change | tolerance/resistance to abiotic stresses, including adaptation to climate change conditions |

| more efficient use of resources, such as water and nutrients | more efficient use of natural resources, such as water and nutrients |

| characteristics that enhance the sustainability of storage, processing and distribution | characteristics that enhance the sustainability of storage, processing and distribution |

| improved quality or nutritional characteristics | quality or nutritional characteristics |

| reduced need for external inputs, such as plant protection products and fertilisers | reduced need for external inputs, such as plant protection products and fertilisers |

This table shows that these sustainability criteria are, at least in part, a legal set-up establishing easy access for GMOs to the EU market, reinforcing our path dependency towards industrial farming.

Furthermore, in practical terms, the sustainability provisions within the NGT and Seed Marketing proposals are poorly suited to ensure a genuine contribution to the sustainability of our food systems.

Firstly, a simplistic analysis of traits alone cannot adequately assess sustainability. It is crucial to consider the entire agronomic production system within which the plant will grow, along with the economic and social context surrounding seed production and use.

Secondly, these provisions open the door to greenwashing. By introducing a sustainability checklist into the NGT-cat.2 authorisation and seed registration process, both proposals give companies the opportunity to declare or label their seeds as sustainable without considering how they will be used.

Thirdly, there is a lack of independent verification for sustainability claims made during the NGT 2 authorisation process. According to the NGT proposal, the producer’s information on alleged “sustainability-relevant” characteristics is not subject to scrutiny. While sustainability characteristics are supposedly tested through VSCU testing, not all traits can be effectively examined (for example, the test does not encompass all resistances or nutritional values).

Lifting the veil on manipulation tactics

Labelling the introduction of genetically modified plants into agriculture as sustainable, despite the associated threats to genetic and biological diversity, the elimination of freedom of choice, and the substantial hindrance of breeders through patents, is absurd.

And it is not only absurd, it’s also a manipulation of public opinion, as recent events in the first negotiation stages of both texts reveal. Last week, Herbert Dorffmann, Parliament’s rapporteur for the Seed Marketing legislation and member of the EPP, published his report proposing amendments to the text. While the Commission’s proposal includes provisions that require Member States to register Herbicide Tolerant (HT) varieties in order to define the minimum conditions for their cultivation (e.g. crop rotation), Herbert Dorfmann is in favour of simply deleting those provisions.

In the first draft of the NGT proposal leaked in June by ARC2020, HT GMOs were supposed to be excluded from NGT-cat1 (GMOs that don’t need to go through authorisation and risk assessment). But in the final proposal, this exclusion was deleted. The Commission then justified it by ensuring provisions would be included in the Seed Marketing Legislation that would compensate for that change. Now a few months later, the pressure is already mounting to delete those provisions, as proposed by the EPP.

Cultivating diversity locally: the right vision for systemic transformation

As we delved into the connections between the GMO deregulation and seed marketing proposals, a crucial question emerged: Could a robust reform of the seed marketing legislation deliver on the sustainability commitments outlined in the GMO proposal, on its own?

We hold the belief that this is the case, and advocate for a safer approach: endorsing the established and proven solution of seed heterogeneity.

For that purpose to be effective of course, the reform of the seed marketing legislation should include concrete measures ensuring the free and easy development of a diversity of plant genetic resources produced and adapted locally, by all the players concerned, across all European territories. And this should be done by supporting and recognising the pivotal role played by population varieties of seeds in agricultural resilience.

Thanks to their indigenous and evolving characteristics, population varieties of seeds are much more responsive to the effects of climate change. They can support the needs for transitioning to organic and agroecological practices, while respecting local contexts, needs and stimuli. By connecting the needs of agri-food players in a given area, from seed production to end products, they also contribute to strengthening short supply chains and to reviving the knowledge and solidarity of farmers and rural communities.

One big concern regarding the spread of new genetic modification techniques – developed as part of R&D programmes designed over several years – is that they would further concentrate production capacity in the hands of agribusiness. In contrast, promoting the autonomy of farmers and rural communities in using locally adapted crops appears to be a much more effective approach in restoring meaning and sustainability to agri-food production chains.

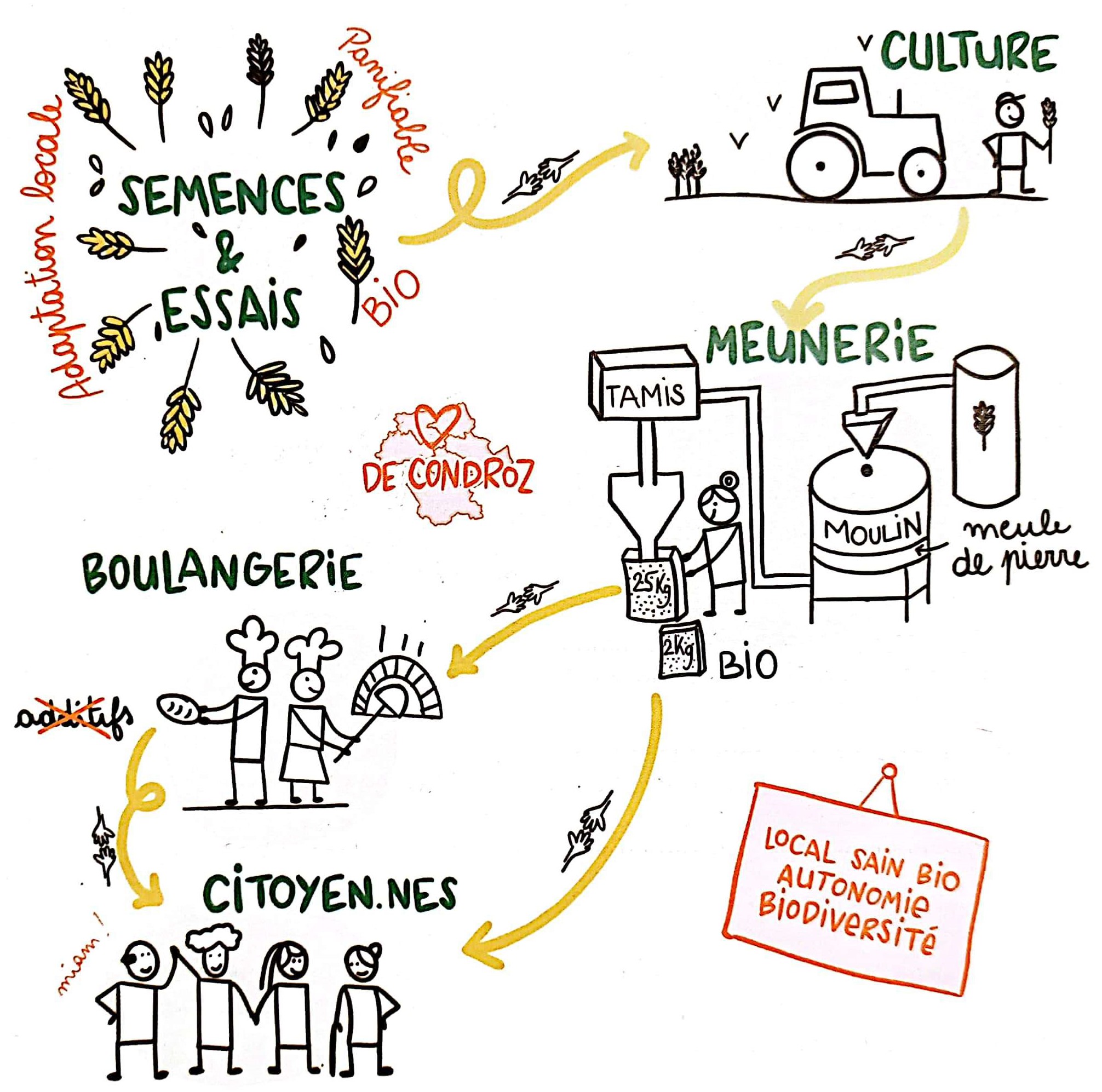

Through the Seeds4All project, we are notably observing and documenting the positive effects for rural areas of the reintroduction of population varieties adapted to the particular issues and needs faced by a specific territory. A noteworthy example is the project Au Coeur du Pain implemented in southern Belgium, and which succeeded in (re)creating a hyper local bakery chain from seed selection to bread selling. Counting on the support of local consumers, this project has led to the reintroduction of a local milling industry and to the positive growth (economic but also ethical and personal) of several bakers’ activities. Find out more about that story and many more on the Seeds4All website.

Crossroads

Allowing for those examples to multiply is not enough though, because it would not ensure their livelihood and development in the long-term in a context when industrial production of GMOs is exploding.

It is crucial to recognise that the decision – to prioritise GMOs, or local seed production and adaptation – carries a significant path dependency that will likely shape the future of our food systems for decades to come. And the basis on which each option should be developed makes it is impossible for these two paths to let them compete in a free market, without strong regulations ensuring fairness and safety throughout the process.

We are facing a choice. Regulating strongly or letting loose. And the Commission should look at its own words in the Farm to Fork strategy to guide this decision. The Farm to Fork strategy did not originally mention NGTs nor did the Green Deal. But from the outset, F2F contained two clear commitments to seed diversity:

- “Sustainable food systems also rely on seed security and diversity.”

- “The Commission will take measures to facilitate the registration of seed varieties, including for organic farming, and to ensure easier market access for traditional and locally-adapted varieties.”

Stick to it.

More on Seeds

EU Seed Law Reform and New Genetic Engineering – Double Attack on our Seeds

Old Varieties and Short Production Circuits to Rebuild “Rural Solidarities”

Adapting Agricultural Practices to Climate Change – Seeds, Beans and Lessons from the Ground Up

Irish Tour part 1 – Agrobiodiversity as a Key Driver for Rural Revolution

Organic and Biodynamic Viticulture: Adapting the Vine in a Changing Climate

More on NGTs

Bugs from a Jug – Gene Edited Plants are Not the Only Things to Worry About