By Adèle Pautrat

In June 2023, we took advantage of the first fine summer days to visit a project run by the Réseau Meuse-Rhin-Moselle (RMRM), one of our close partners. Comprising around ten member associations, the RMRM aims at supporting and connecting initiatives that promote the preservation of old varieties and peasant breeding practices, in an area bounded by the three rivers that give it its name.

In this framework, it has recently been supporting the development of short supply chains such as “Au Cœur du Pain”, which aims to reintroduce local varieties of bread cereals adapted to the specific characteristics of a region located in the south of Belgian Wallonia: the Condroz.

Landraces and their local roots as a starting point for developing short, sustainable supply chains

Like many European agricultural regions dispossessed by the agro-industrial revolution, Wallonia is facing a major problem in cereal farming.

The F1 hybrid varieties that are mainly grown there have been selected by the agro-industry on the basis of tests carried out in the Hesbaye silts, “the good soils” as Marc van Overschelde calls them in an interview given to Valériane, valued by an agricultural model that is entirely focused on productivity.

Whether organic or conventional, these varieties are poorly adapted to the specific agricultural characteristics of Wallonia, and do not meet neither the needs of small-scale farmers for autonomy, nor the desire of new bakers to have access to top-quality raw materials.

Faced with this situation, professionals and associations are mobilising to reintroduce and promote local and farmhouse varieties, both ancient and modern, capable of meeting and adapting to the requirements of each terroir, to the need to develop farming practices and to new nutritional and taste requirements.

And this can only be done within the framework of dynamics linked to limited territories and in direct collaboration with the players living in it; that is to say, in very short circuits.

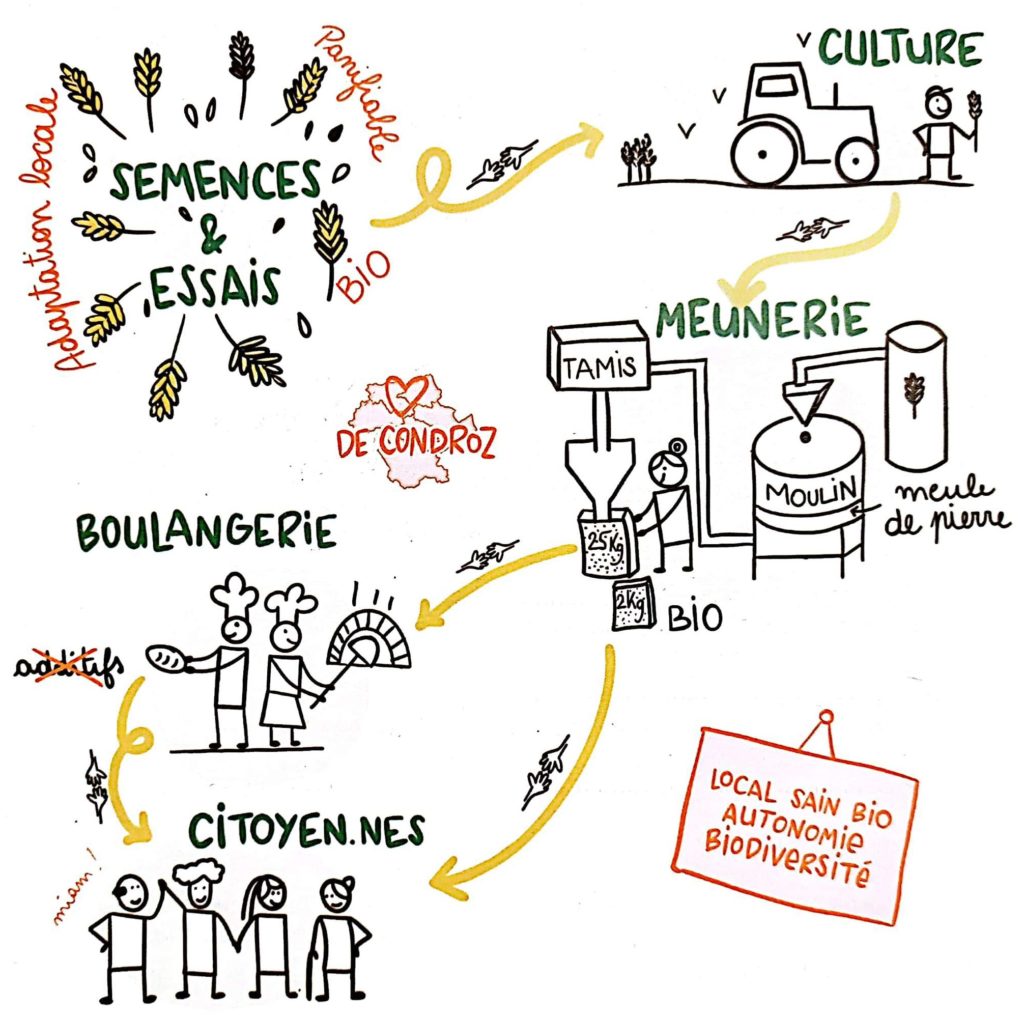

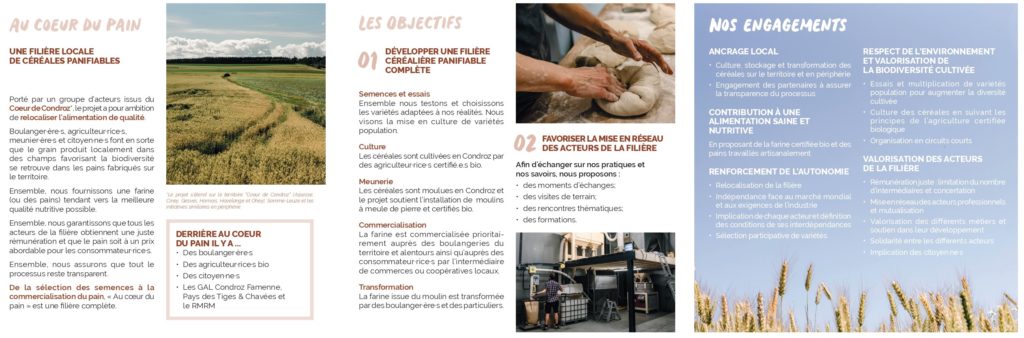

Au Cœur du Pain: hyper-local bakery chain, from seed selection to bread selling

Launched in 2020 on the initiative of the RMRM, the Groupe d’Action Locale (local action group – GAL) Condroz-Famenne and the GAL Pays des Tiges et Chavées, “Au Cœur du Pain” has strong ambitions: to relocate food production, to guarantee fair remuneration and prices for all members of the filière, and to promote and develop cultivated biodiversity.

It is based in the “Cœur de Condroz” region, the epicentre of small-scale organic seed production in Wallonia, where Semailles, Cycle-en-terre and Anthesis are based.

The Condroz has a population of around 50,000, a large number of farming and processing businesses and a growing number of organic and artisan bakeries in recent years, including two that opened in 2023.

Below are the objectives in French as defined by the founding group: 1/ to develop a complete bread-making cereal sector, and 2/ to promote the networking of actors in the sector.

A first population variety tested in the fields in summer 2023

One of the stops on our summer tour of the Condroz region was a visit to the collection of varieties developed as part of the research work carried out by “Au Cœur du Pain”. It was led by Sofia Baltazar from the GAL Pays des Tiges et Chavées, Corentin Hecquet from the RMRM and Didier Demorcy from the Li Mestère association.

Thanks to the conservation work carried out in the region by numerous individuals, groups, associations, etc., “Au Cœur du Pain” has been able to collect 34 old varieties of wheat, durum wheat, barley, rye, spelt, small spelt, egilope, starch, etc.

All are being tested on microplots at the Haugimont estate (UNamur), as part of trials designed to compare their behavioural development. Based on agronomic observations, the most interesting varieties are gradually selected, given the agricultural context of the Condroz and the ambitions of the network, such as low-input cultivation.

These varieties are then mixed to create ‘populations’, which are deliberately not fixed or stabilised, and are therefore dynamic and renowned for their great potential for resilience and adaptation.

In spring 2023, a first mix of 11 varieties, the mixo 11, was sown on 0.5 hectares at the Corioule farm, owned by Guillaume, an organic farmer and member of the “Au Cœur du Pain” network.

As a collective and supportive dynamic, the short circuit creates favourable conditions for a return to seed autonomy

Guillaume’s farm, certified organic since 2013, is located in the village of Assesse, near Namur. It covers 120 hectares of land devoted to raising cattle and growing pulses and cereals.

Guillaume joined “Au Cœur du Pain” very early on, being already involved in the organic growing of two modern varieties of bread-making wheat: Alessio and Arminius. Accompanied and coached by members of the RMRM and the GAL, he decided to embark on trials growing old varieties.

“Producing these varieties is not a problem. What is holding us back is the lack of outlets” and therefore the difficulty in anticipating the value of experimental production and planning a return on investment.

In a context dominated by the cultivation of hybrid varieties developed ex-situ, combined with a loss of farmers’ know-how in terms of varietal selection, it is very difficult for a farmer to make the transition to old varieties alone. This often involves a significant increase in working time and risk taking.

It is precisely thanks to the collective dynamics embodied by cooperatives, networks or short supply chains that the process of reappropriating seeds by those who sow them is made possible.

The farmer becomes a link in the experimentation chain. Surrounded by many other players, motivated in particular by the desire to support his.her autonomy in terms of seeds, he.she has the opportunity to express his.her needs and expectations, and to set his.her limits. The time invested and the risks are shared. And the outlets are assured.

This summer has been decisive for Au Cœur du Pain: in October, bread-making tests will be carried out to assess the baking quality of mixo 11. If they are conclusive, the first products based on locally sourced organic ancient wheat flour could be marketed – a formula that’s on the up and up!

A project that also reflects the changing face of the bakery industry in Wallonia

In Belgium, at a time when traditional bakeries are in decline, the profession has been attracting a growing number of people looking to change careers.

Driven above all by the desire to offer breads with high nutritional value and taste, these neo-bakers are bringing traditional skills back into fashion, as opposed to industrial production methods.

They don’t necessarily have shops, but rather production workshops, and sell mainly through distribution outlets or by delivery to individuals.

Because they are concerned about their personal well-being and/or because they combine different jobs, they try to limit the development of their bakery activity within limits that are compatible with their professional situation and their private life.

A set of choices that reflect a model that places them de facto in a short circuit logic – and makes bread lovers very happy!

The point here is not to blame so-called traditional bakeries, but to acknowledge the deleterious impact that the industrial production model has had on their job. The comments made by Axel Colin, a baker and member of the Li Mestère association, in issue 126 of Valériane sum up the situation quite well:

“Industrialisation was the only option chosen, as it was supposed to make the job easier (…). In fact, it has reduced things to the point where the job has completely vanished. These guys we call bakers still get up at night to bake the frozen dough delivered to them. Basically, the only thing they kept from the job is to get up at night…”

The short circuit as an space for transparency

Chloé and Gauthier, bakers and members of Au Cœur du Pain we were lucky enough to meet in their production workshops, are very representative of this new, alternative and committed generation.

Chloé owns the Chouette enfarinée bakery. She lives and works in Crupet, in a former farmhouse acquired through a shared housing project. She has set up her production workshop in the community kitchen, which she uses one day a week to produce 3 batches of bread ; around 120 breads that she sells through various outlets.

Gauthier discovered baking skills during a long cycling trip around Europe and several experiences of life in a community. On his return, he trained as a baker and then set up La grigne de Gauthier in Porcheresse, with a production workshop that he first shared and now occupies alone. He doesn’t have a shop either, and distributes his products via organic outlets and local markets.

When asked about their reasons for joining Au Cœur du Pain, both immediately mention health, nutrition and the desire to offer quality products. The short, supportive supply chain gives them access to raw materials that they can source from producers they know and with whom they work, exchange ideas, test and improve their practices.

Transparency is at the top of the list of things they want to guarantee their customers as bakers. And until recently, this posed a major challenge to the development of the network: its milling independence.

“The mill was the last missing link in ensuring the traceability of cereals”

For a long time, Chloé and Gauthier were faced with the same problem: there were no mills in the Condroz offering organic milling. They were forced to send stocks of grain purchased from their partner farmers, several dozen kilometres away.

As well as generating additional transport costs and CO2 emissions, the absence of a local mill limited the traceability of cereals and therefore the transparency of finished products.

In fact, ever since the Au Coeur du Pain network was launched, one of its priorities has been to explore possible alternatives for starting up a mill in the region. After much discussion and consideration of the feasibility of it, Guillaume, the farmer, agreed to install one on his farm.

He sees this decision as the logical extension of his commitment to organic farming and short distribution channels. Noting the consumers’ attraction to traditional bakeries and the increase in local demand for organic wheat flour, he is also convinced that diversifying his business will enable him to make better use of his production and control his selling prices.

Guillaume has opted for a milling system that straddles the line between craft and industry: his stone mill is fully automated, so he hasn’t had to hire any new staff. “Automation allows diversification,” he says, “I use technology to continue to exist.”

To exist and to progress. In the image of what the network seems to generate. As our visits progressed, we couldn’t help but notice the positive, caring dynamic characterising the people we met. Aware of the current socio-ecological issues, they are keen to do well, to work together and to remain united around common goals and values.

Old varieties and short production circuits to revive “rural solidarities”

To round off our cereal tours of the Condroz region, we had the pleasure of attending a talk entitled “Histoire de blés et d’Occident” (History of wheat and the West), written and performed by Didier Demorcy.

In that conference, he discusses, among many other things, the “destruction of rural solidarities” caused by the spread of systems of monetarisation and then capitalisation of agricultural exchanges – which led to major peasant revolts from the 16th century onwards.

The old variety, which thanks to its indigenous and evolving characteristics escapes the logic of marketing and privatisation, thus becomes the symbol of a possible resistance by rural and agricultural communities, of their capacity to reorganise together the management of resources and means of production.

The “Au Cœur du Pain” network, while enabling the development of viable economic activities, also responds to human, ecological and social issues specific to the Condroz region that require solutions based on solidarity.

Exchanging best practice, learning from each other, helping each other, benefiting from collective power, are just some of the reasons why Guillaume, Chloé and Gauthier joined the network and persevered, despite the difficulties they encountered, to offer the best possible products and practices.

This model encourages improvement. It drives individuals to do their bit and take responsibility for the sustainable development of their communities and territories. It offers concrete, tangible solutions to urgent environmental and climate issues.

In a way, it carries the seeds of a different model of society – that we wish to see spread everywhere!

More

Adapting Agricultural Practices to Climate Change – Seeds, Beans and Lessons from the Ground Up

EU Seed Law Reform and New Genetic Engineering – Double Attack on our Seeds

Irish Tour part 1 – Agrobiodiversity as a Key Driver for Rural Revolution

1 Trackback / Pingback

Comments are closed.