Few cliches are more hackneyed but also more prescient than “a week is a long time in politics”. But what a week Simon Coveney, Ireland’s Minister for the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and the Marine had last week.

In a previous article, ARC2020 pointed to media coverage that suggested Coveney as a potential future leader of what is current largest party in government, Fine Gael. This may still emerge in time, but there is no doubt that Irish agriculture and the minister has been rocked by a new meat scandal. And if history tells us anything, its that in super-integrated global agri-food trade, problems can spread rapidly.

In a previous article, ARC2020 pointed to media coverage that suggested Coveney as a potential future leader of what is current largest party in government, Fine Gael. This may still emerge in time, but there is no doubt that Irish agriculture and the minister has been rocked by a new meat scandal. And if history tells us anything, its that in super-integrated global agri-food trade, problems can spread rapidly.

This problem emerged when, on the 15th January, the Food Safety Authority of Ireland found traces of pig and horse DNA in 10 of the 27 beef burgers tested. The FSAI stated:

“A total of 27 beef burger products were analysed with 10 of the 27 products (37%) testing positive for horse DNA and 23 (85%) testing positive for pig DNA. In addition, 31 beef meal products (cottage pie, beef curry pie, lasagne, etc) were analysed of which 21 were positive for pig DNA and all were negative for horse DNA…

The beef burger products which tested positive for horse DNA were produced by two processing plants (Liffey Meats and Silvercrest Foods) in Ireland and one plant (Dalepak Hambleton) in the UK. They were on sale in Tesco, Dunnes Stores, Lidl, Aldi and Iceland.”

Meanwhile, Tesco’s share price has been dropping rapidly.

While pork is processed in the Irish plants in question, horse is not, as Ireland does not have a tradition of slaughtering or eating horse. So while there is something of a cultural taboo around horse meat in Ireland, the primary issue is traceability – just where did this horsemeat come from? Irish agriculture prides itself on its traceability systems, and uses them as a marketing tool globally.

The agri-food sector is a core part of the Irish economy, while the majority of Irish farmers are livestock farmers who carry cattle. County Cork in the south west has an incredible one million cattle, the largest number of any country on the island. And while traceability is the primary concern, markets in Muslim countries, such as the recently opened Libyan market, would no doubt fret at the thoughts of pork in beef burgers.

Worryingly, Irish meat processor ABP, who’s subsidiary Silvercrest’s processing plant is one of the two implicated in the scandal, states on its website that it has not been routinely testing for other animal DNA.

In all of this, dark humour has emerged in Ireland, the UK and now also further afield.

Curiously little attention has been paid in Ireland to the investigative journalism of John Mooney. Picked up by the BBC and Channel 4 in the UK, Mooney’s reports in the Sunday Times last May uncovered illegal trade in Irish horses for meat. Since the economic collapse, many in Ireland have found horses too expensive to keep, and have effectively abandoned them. Mooney’s reports also found connections to criminal elements in the illegal horse meat trade, with horses used to smuggle drugs and money on route to slaughterhouses in the UK for meat processing, using, he claims, forged papers.

Mooney cites USPCA representative Stephen Philpott, who claims “we have been following lorryloads of horse to abattoirs in Ireland, the UK and Europe for months now. We have watched abattoirs being opened late at night so people can deliver lorryloads of horses and have them slaughtered in the middle of the night”.

On the 17th January, Philpott reiterated his claims, pointing to “denial” and “spin” in order to protect “vested interests”, though he also said that “we cannotnecessarily say that they (horses) are ending up in the Republic of Ireland” which may suggest that his actual sightings were of abattoirs in the UK.

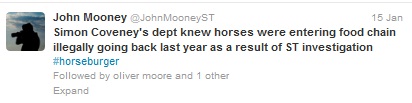

Mooney however, has tweeted this week that “Simon Coveney’s dept knew horses were entering food chain illegally going back last year as a result of ST investigation” and “We ran big investigation last year into illegal slaughter of horses at Irish abattoirs.”

The saga deepened when Irish Minister Eamon Gilmore revealed that the first tests were conducted in mid November, which in itself caused front page headlines the next day.

And with a prominent but controversial meat processor, Larry Goodman of ABP, at the centre of it all, this story will run and run. (Insert horse racing pun here!) One thing is for certain – this has been a rollercoaster first two weeks for the Irish presidency of the EU.