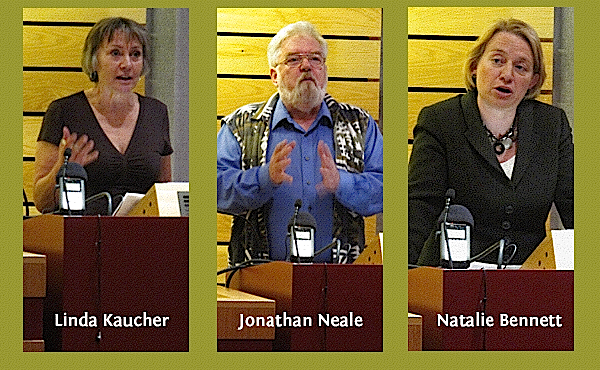

Dozens of UK anti-TTIP campaigners recently filled a London lecture theatre, organised by the Stop TTIP campaign. The audience had come to hear the environmental case against the secretive so-called Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership trade deal currently being negotiated away from democratic accountability. UK Green party leader Natalie Bennett (pictured, right) warned that the treaty involved: “…handing over power…” and that the consequence would be unacceptable industrialised food processes, such as chlorinated bathes at the end of chicken processing lines to counter unecessary contamination caused by high throughput rates.

Dozens of UK anti-TTIP campaigners recently filled a London lecture theatre, organised by the Stop TTIP campaign. The audience had come to hear the environmental case against the secretive so-called Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership trade deal currently being negotiated away from democratic accountability. UK Green party leader Natalie Bennett (pictured, right) warned that the treaty involved: “…handing over power…” and that the consequence would be unacceptable industrialised food processes, such as chlorinated bathes at the end of chicken processing lines to counter unecessary contamination caused by high throughput rates.

This is just one example of the innocuously-named regulatory harmonisation agenda that will allow corporate interests to cherrypick the most lax regulations from whichever side of the Atlantic best suits their purpose. Bennett is in favour of working with Europe, but wants to see root and branch changes: “We need the EU, but a profoundly reformed EU,” she explained.

Environmental writer Jonathan Neale (pictured, centre) warned that despite reassurances to the contrary, regulatory harmonisation is: “…a race to the bottom.” The ISDS dispute procedure gives UK and EU businesses the opportunity to get round government regulations. The meeting heard that the current Quebec tar sands dispute was being mounted from the US office of a Canadian-based corporate.

“We have to break through the bonfire of regulations,” Neale argues, if we are to preserve the environment from deregulated growing of palm oil or deregulated extreme fossil fuels. “Renewables will need knowledge sharing,” he added, warning of a risk to the environment through the commercially driven intellectual property rights agenda. Victories such as the South African generic drugs campaign demonstrate that political will and an appetite for constructive change can be created, even if it takes time and determination.

Trade researcher Linda Kaucher (pictured, left) reminded those present that TTIP was not about trade but policymaking being written by corporations. “The trade [section of the] European Commission is central to the EU’s structure,” she explained. “What goes on inside the EU and in external trade relations is a continuous spectrum. It’s the same stuff.” For example, “…you can see it at work in public procurement, where the gloves are off.”

Previous ARC2020 articles on TTIP