One of the few bright spots of Brexit is the opportunity the UK now has to rewrite its agri-food and rural rules. To the surprise of many, DEFRA Minister Michael Gove became something of a visionary. His appointment of Tony Juniper, formerly of the World Wildlife Fund and Friends of the Earth, to chair Natural England last year is an example of how the Brexiteer managed to think outside the box.

More importantly, the UK Agriculture Bill, currently winding its way through the Parliamentary process, had some very encouraging elements.

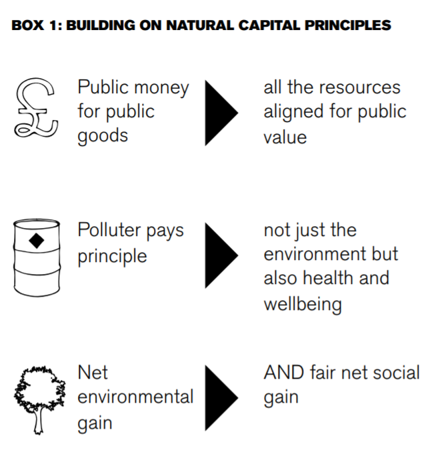

While wary of some of the gaps in the bill, Vicky Hird, campaigner with UK policy platform Sustain lists these as “possible new supply chain regulation and financial support for delivering publicly useful outcomes including: improving the environment; public access; maintaining or restoring cultural and natural heritage; animal health and welfare; and mitigating or adapting to climate change”

Now, Theresa Villers has taken over in DEFRA, and moreover, Boris Johnson has already made soundings towards the US regarding Genetic Modification, the future direction of British agriculture is again in flux.

In this light, the RSA (Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce) report, called “Our Future in the Land” makes for very interesting reading.

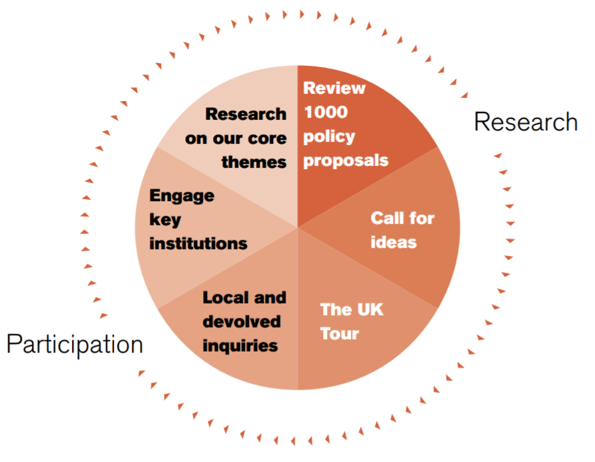

The RSA Food, Farming and Countryside Commission “was established in 2017 to think afresh about where our food comes from, how we support farming and rural communities and how we invest in the many benefits the countryside provides.”

The process used to come up with the “Our Future in the Land”” report was quite thorough, with meetings held all over the UK,further research with farmers, young people and communities on particular emergent issues was conducted, and over 1000 policy proposals analysed.

“We learned early on that sometimes our questions were not necessarily the questions that mattered in the communities we visited.” So says the accompanying “Field Guide for Action”.

This is what was most interesting about this approach – communities and farmers in communities were able to in part shape the process. “In Cumbria, the group focussed on resource and activity mapping, making it more visible to the community itself; in Lincolnshire, on soil improvement and farmer learning; in Devon, the leadership group picked a number of topics: farmer mental health, grasslands, biodiversity, young people in farming.”

Similarly specific areas emerged in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, while 20 farmers were also interviewed to find out how they think about health and wellbeing.

Three Calls to Action emerged from the process:

- Healthy food is everybody’s business – good food must become good business.

- Farming can become a force for change, leading the 4th agricultural revolution towards agroecology.

- The countryside can work for all, as a powerhouse for a new regenerative economy.

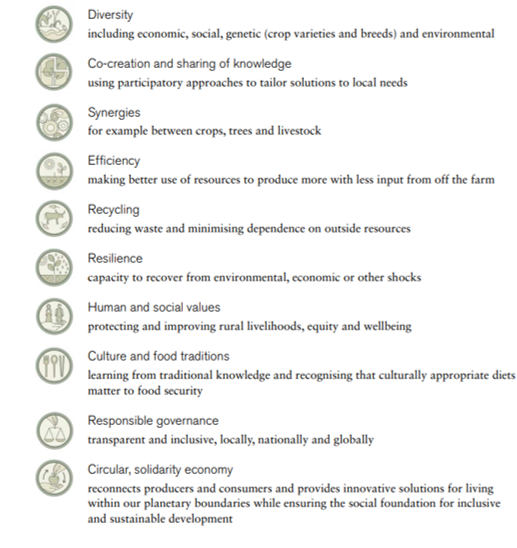

Much of this may sound too broad and generic, but there is already something interesting in the words chosen – especially agroecology.

These buzz words refer to more holistic approaches to land and landscape management, approaches where the integrated, multivarious nature of farming is taken into account.

“We are persuaded that the principles of agroecology best sum up how farming will need to change globally” the authors say. And they use the UN FAO definition of agroecology: “an integrated approach that applies ecological and social principles to the design and management of food and agricultural systems. It seeks to optimise the interactions between plants, animals, humans and the environment and the social aspects that need to be addressed for a sustainable and fair food system.”

So far, so jargony, but this recommendation could make farmers sit up straight in their seats:

“Establishing a National Agroecology Development Bank to accelerate a fair and sustainable transition.”

If policy and then state supports, as well as development bank funding emerge to help farmers adjust farming practices, that would add substance to the soundings.

A version of this article also appeared in the Irish Examiner farming.

Read the reports

RSA report Our Future in the Land

RSA Report Field-Guide for the Future

More on the UK’s food and farming future

Book Serialisation | Creating a New British Farming Food and Rural Policy