Mainstream UK media have presented Brexit minister David Davis (left, without negotiating papers) as the public face of the country’s progress with Brexit talks. However, the press has studiously overlooked the back-room activities of the international trade minister Liam Fox, who has been rolling up his sleeves and starting to size up Tariff Rate Quotas (TRQs) held by the European Union at the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

Mainstream UK media have presented Brexit minister David Davis (left, without negotiating papers) as the public face of the country’s progress with Brexit talks. However, the press has studiously overlooked the back-room activities of the international trade minister Liam Fox, who has been rolling up his sleeves and starting to size up Tariff Rate Quotas (TRQs) held by the European Union at the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

In an extraordinarily wide-reaching plan described as a “Technical Rectification”, Fox is planning to unilaterally carve out what he judges to be the UK’s share of TRQ tonnages for third country imports such as New Zealand sheepmeat and register the results with the WTO. The story emerged thanks to Sky News journalist Faisal Islam, but only because the TV chain was filming Fox in action at the WTO headquarters in Geneva.

In the past, technical rectifications have been more limited in scope, but this editing is on an industrial scale: Fox is not waiting for Davis to get round to discussing trade with the European Commission before trying to unpick TRQ tonnages. These have been shared for decades by the EU 28 and the UK still supports them, technically. By waiting for the holiday season, Fox can improve his chances of getting away with a technical fait accompli and pre-empt any discussions on trade later in the year.

Meanwhile, other aspects of Brexit fallout have been observable for a number of months, notably sagging Sterling exchange rates against the Euro. There is also an unseemly scramble by UK food retailers to secure any spare domestic procurement capacity, so at least somebody is reading the writing on the wall. But this, a year on from the referendum, is just the beginning of a wider structural crisis.

The problem is that the UK has not had a coherent food policy for decades and imports about half its food. It also depends on recruiting a lot of foreign seasonal labour to pick, pack and process many of its domestic crops. Not to mention factory hands to mind the food industry’s production lines.

With an aging, urbanised population, the UK is hardly in a position to gripe about younger, active migrant workers coming to swell the ranks of the working population. Still less to make the free movement of EU labour a red line issue in the Brexit agenda.

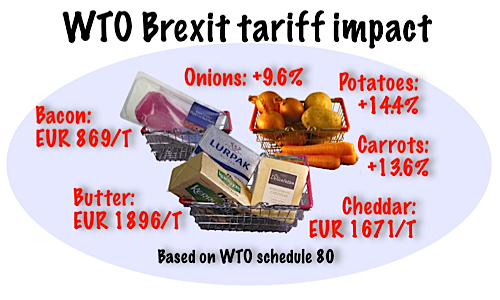

Some aspects of the coming storm are knowable in advance, such as the WTO schedule 80 agrifood tariffs that will apply to the UK if it leaves the European Customs Union and becomes a third country. Tariffs from this schedule can be identified and downloaded from the WTO website at http://tariffdata.wto.org/default.aspx by navigating the online database.

The infographic gives a few examples of percentage (ad valorem) and fixed tariffs for some very basic internationally-traded foods. Many schedule 80 rates, notably beef and dairy tariffs, were deliberately set high enough to dissuade member states from trading in these commodities with third countries.

The infographic gives a few examples of percentage (ad valorem) and fixed tariffs for some very basic internationally-traded foods. Many schedule 80 rates, notably beef and dairy tariffs, were deliberately set high enough to dissuade member states from trading in these commodities with third countries.

Nobody seriously expected any member state would be foolhardy enough to contemplate becoming a third country on these terms. But there is no accounting for the damage that can be done by a bunch of bone-headed bigots with more media fire-power than common sense.

The problem with eye-wateringly high tariffs is exactly that: they are eye-wateringly high and can often double the cost of imported goods at the point of entry. Nobody in their right mind would contemplate trading under them for real unless they were between a rock and a very hard place. But more of that later.

One of the most intractable Brexit crossroads where geography meets ill-fated history has to be Ireland. Take dairy, for instance: Northern Ireland exported 80,000 tonnes of fresh milk to the south in 2016, of which 12,000 tonnes went to bottling lines for home consumption and the rest went to making butter, cheese and skim milk powder.

If this milk had arrived as a third country import, it would have cost EUR 218/tonne in duty or EUR 17.4 million over the year, in addition to the cost of the milk. In a processing context, with March 2017 manufacturing milk prices topping EUR 300/tonne, a hard Brexit and leaving the customs union would shut down cross-border manufacturing milk deliveries overnight.

Ireland currently exports 78,000 tonnes of Cheddar to the UK, which is the only European mass market for this cheese. Once again, let us assume that the UK adopts unchanged WTO schedule 80 agrifood tariffs. At EUR 1671/tonne for Cheddar, the UK government would rake in just over EUR 13 million a year from the supermarket own-label Cheddar category alone.

Importantly, the UK currently acts as a bridge to the rest of Europe for Irish agri-food exports. The alternative – tariff free travel via France – would take many hours longer.

As a recent Politico.eu article pointed out: “It is impossible to overstate the importance of the British transit route: Some 80 percent of the Irish road freight that reaches mainland Europe passes through the U.K.

“Ireland is reliant on that accessibility to the U.K. more than any other country in Europe,” said Aidan Flynn, a manager at Freight Transport Association Ireland.””

Elsewhere, I have calculated that the UK government would stand to collect about GBP 7 billion (at 2015 levels) from taxing imported food through the wholesale adoption of WTO schedule 80 tariff rates. This huge administrative cut and paste operation could be a quick and dirty solution for Brexit negotiators running out of time. Or if Davis turns up without his position papers. Again.