A new report by IATP and GRAIN out this week highlights the devastating impact of the meat and dairy giants on the environment. If GHG emissions from this sector continue as predicted, the Paris Agreement goals are firmly out of reach.

Comfortably nestled in a city with vegan and vegetarian haunts cropping up on every street corner and the widespread promotion of ‘flexitarianism,’ the alleged ‘food trend of 2017,‘ it is easy to forget the global picture. Whilst it is true that in the UK, meat consumption has been on a steady decline for some years, global meat consumption is on the up. The climate consequences of this are profound, particularly when it is coupled with the corporate consolidation characteristic of the contemporary global food regime.

The new report co-authored by the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy (IATP) and Grain, highlights the extent of the problem. The meat and dairy sector is dominated by a few large companies such as JBS, Cargill and Tyson Foods. Whilst it has been clear for some time that the meat and dairy sector has a massive carbon footprint, there is astonishingly little publicly-available data on the carbon footprint of these individual companies.

This information is needed to measure extent and responsibility, to hold these firms directly accountable for their emissions and ensure their contribution to meeting carbon reduction targets. In the absence of this data, ITAP and Grain used the Global Livestock Environmental Assessment Model (GLEAM) developed by the FAO, with corporate data on production volume to make approximate GHG emissions calculations of the 35 largest beef, pork, poultry and dairy companies worldwide.

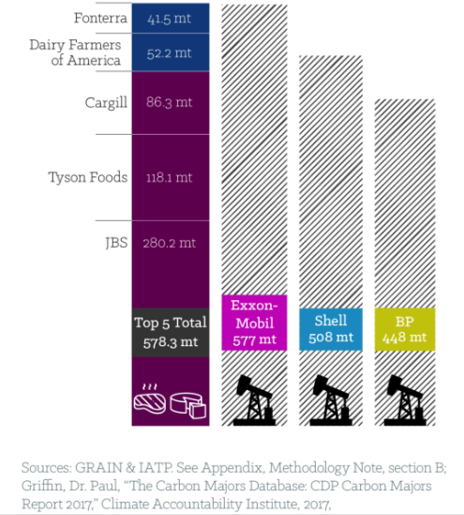

The research is shocking. The combined annual GHG emissions of the five largest meat and dairy companies is greater than that of Exxon-Mobil, Shell or BP. If one were to combine the emissions of the 20 largest meat and dairy companies, this would be greater that the annual GHG emissions of Germany, Canada, Australia or the UK.

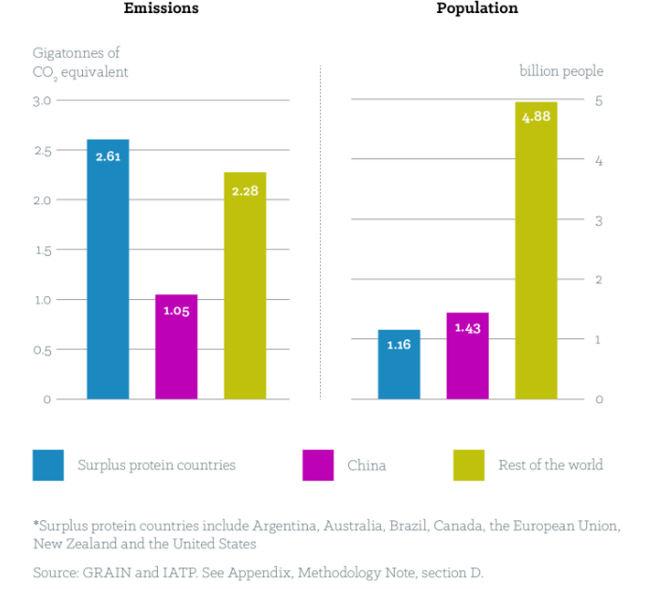

It’s important to note that these 35 companies are not equally geographically dispersed. They are concentrated in a few countries with a disproportionate share of meat and dairy production and consumption. These include the U.S., Canada, countries in the E.U, Brazil, Argentina, Australia, New Zealand and China. Together they are responsible for over 60% of GHG emissions from meat and dairy production. Per capita, this is about twice as much as the rest of the world.

Particularly disturbing in light of these findings is the wide-scale non-reporting of emissions estimates let alone of emissions reduction targets. The supply chain emissions – upstream and downstream emissions not directly produced by the given company but including things like livestock feed production or methane from livestock – usually account for between 80% and 90% of the emissions of that company. Of the 35 companies accessed, only four provided thorough emissions estimates including supply chain emissions.

In order to have any hope of meeting the Paris Agreement goals of keeping global warming to below 1.5 degrees Celsius, these companies need to be on board. If the meat and dairy industry continue to grow as projected, the sector could account for 80% of global GHG budget.

However, fewer than half of these 35 firms have released any emissions reduction targets and of those, six have integrated those emissions from the supply chain. This is because not only is it not in their immediate interest to reduce GHG emissions, but they actually plan for increased global consumption of meat. “The only common element in this jumble of corporate promises and inaction on climate change is a commitment to growth,” the report states. As an example, the authors open with the case of meat giant JBS who “told shareholders that a pillar of its strategy is a projected 30 percent increase in per capita global meat consumption to 48kg by 2030, up from 37kg per person in 1999.”

To contextualise: a Greenpeace report from earlier this year found that, to avoid dangerous climate change, per capita meat consumption must drop first to 22kg by 2030 then 16kg by 2050. The report is clear: “the paradox of the corporate business model based on high rates of annual growth versus the urgent climate imperative to scale back meat and dairy production and consumption in affluent countries and populations is untenable.”

Of course, the environment is not the only loser. “For farmers, the growth of big meat and dairy operations continues to be an unfolding disasters,” the authors write. “In Europe and North America, the relatively few small and medium-sized producers who are not wiped out by agricultural policies that are biased in favour of agribusiness, often find themselves trapped in unfair supply arrangements dictated by these companies, with limited access to other buyers,” the report states. This is problem extends to the Global South, where small farmers are often pushed off their land by large agricultural firms, or are unable to compete with the dumping of subsidised meat and dairy on their markets.

As is, the industrial meat and dairy sector is untenable for the environment, small and medium-scale farmers, public health, workers and animal welfare standards. The report states, however, that “this production is only made possible because the corporations receive an indirect subsidy from taxpayers in the form of government-funded price supports that keep grain cheap.”

Achieving our environmental and social goals requires serious regulation of the industry and a redirection of the subsidies which keep it afloat, the report concludes. These funds should be geared toward an agroecological transition where consumers, farmers, animals and the environment are prioritised over big business.