We’re back on Cortijo El Manzano in Campotéjar, Spain, with a third and final letter from rural Andalusia by ARC2020’s Matteo Metta. Though committed, this agroecological farm, under pressure from all sides, has little bandwidth to invest in digital tools, as he learned while volunteering on the farm in February. Energy and infrastructure, labour and skills, local contexts, and the values of the farmers, are among the factors that must be taken into account if meaningful digital solutions are too emerge for small, mixed agroecological farms such as this one. Reflections by Matteo Metta.

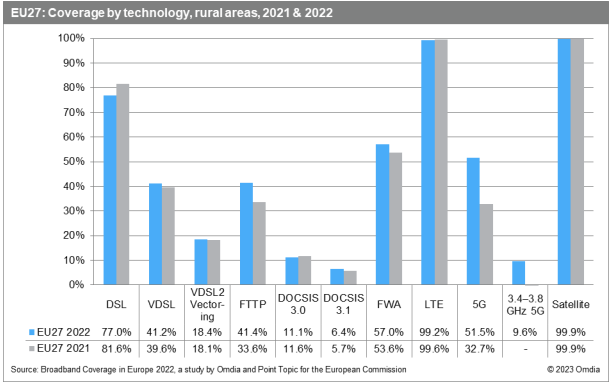

In terms of connectivity, European rural areas – despite all their differences – are reaching a point where basic internet coverage is accessible in one way or another: DSL, satellite, fibre optic, wireless, etc. Of course the public ownership, sovereignty, quality (speed, latency), the costs, and the full coverage remain questionable aspects of European Union telecommunications infrastructure. The discrepancies with urban areas, especially as regards 5G technologies, are well known.

The figure below shows the latest data on broadband coverage in EU rural areas. Except for DSL, all other technologies for internet connectivity have made some progress between 2021 and 2022. In some cases, these technologies are reaching almost universal coverage in rural areas: LTE or 4G wireless networks and satellite coverage is close to 100%.

At El Manzano, internet is accessible only via mobile broadband (4G), and only in certain points of the house and field, namely those better exposed to the antennas. A week on this farm brought up many critical aspects of digitalisation that we can learn from rural areas, from demography to dependencies. However, here I’d like to share some observations that were so tangible in El Manzano and can inspire just digital agriculture programmes with a rural and peasant agroecological perspective.

This farm is overwhelmed with the everyday work and the diversity of living relationships to care for: animals, plants, cheesemaking, sales, etc. Doing all this under steady and increasing pressure from all sides takes digital conversion off the high-priority list. It is as if the prospects for introducing something new or beyond the farm’s capacity are too distant from the everyday, precarious reality of El Manzano. In some cases, digitalisation clashes with the physical and social equilibrium on the farm, such as operating with low energy consumption, running an agroecological business with little fossil fuel use, nurturing in-person relationships, and so forth.

When I asked Rafa about his views on digital technologies after a long day in the field, he did not oppose the idea of someone on the farm communicating online about the farm activities, or using software to manage direct selling and farm stays. Actually, these innovations would be very welcome at El Manzano as long as they are balanced with the rest.

However, in the current state, Rafa simply feels that he cannot commit to more. Without someone from within the farm stepping up, he cannot lead on this, nor can he externalise these innovations to a delegated actor because he will have no capacity to follow up and actually benefit from it. As a result, the transformative power advocated by many digitalisation proponents remains a hard sell to these long-established and still active rural actors. Here I try to summarise two of the many reasons.

A first tangible issue with rural digitalisation at El Manzano, but most probably on many other farms, is connected with the physical world: hardware, infrastructure, and energy. Many believe that effective rural digitalisation needs just a smart phone and internet connection, and I am sure that many rural dwellers want even less than that.

However, farms like El Manzano cannot afford a stable energy connection, a PC, a mouse, a keyboard, a desk, a chair, and a room oriented towards antennas in order to effectively respond to the demands and opportunities of digitalisation. And therefore, farms like El Manzano remain totally cut out of the rural digitalisation discussion.

A second issue is related to labour, skills, and scale of work. The advantages of digitalisation in mixed farming can be grasped when the positive returns overcome the opportunity costs involved in setting up, maintaining, and improving a digital system. Especially in the context of agroecology, whereby farmers maximise their own capacity, labour, and resources to minimise external dependencies, unless digital labour and skills are insourced or provided in cooperation with trustful and stable outsiders, the farmers will refrain from moving into areas where they can become vulnerable or exposed to dependencies such as consultants, temporary volunteers, and so forth.

Furthermore, time and knowledge investments into the digital domain are weighed by the farmer in relation to the investments required in the physical and social sphere (people, food processing equipment, etc.). Finally, farmers also consider the scale of their work, in terms of number of clients, transactions, frequency, monetary value, time saved. The variables in the digital equation are many.

All in all, I learned that any public efforts to digitalise rural areas cannot draw straight boundaries with other structural and social policies, nor can they rely on decontextualised, top-down plans. As for cases similar to El Manzano, European programmes mainstreaming digital skills, technologies, or telecommunication infrastructures in rural areas may miss their key target groups and fail to stop agricultural and rural decline if they do not work hand-in-hand with broader agri-food-rural policies. Factors that go beyond the pure digital realm cannot be put aside, especially the (often precarious) physical and social conditions of farmers.

Actions beyond tractors

In these letters from Cortijo El Manzano, I have tried to tease out some of the many stories of progressive agroecological actors and alliances that embrace rural development with nature and people in rural Spain. Some ingredients of rural resilience from Andalusia have been unpacked, but many more deserve special attention.

A tractor, El Manzano does not have. Time to beg for better policies, neither. But probably many concrete actions and inspirations to deal with existential rural problems. The housing conditions, but also market, labour, and climate are not giving good, long-term prospects for generational renewal. This is clearly visible by walking around El Manzano. What El Manzano needs to avoid the same path is a system change and collective support – at all levels. Forty years of agroecological work cannot be completely lost. It will be a loss for Andalusia, but also for the food, rural, and agricultural heritage of the entire world.

Agroecology is often criticised for not being a scalable model as it would actually require more land to ‘feed the world’. Well, El Manzano reminds us that, without chemicals and with a minimal or zero consumption of fossil fuel, agroecology feeds people and takes care of the environment without putting pressure on it. At the same time, we need to start realising that continuing with business-as-usual models may require more planets than our beloved Earth. Farms so rooted in el campo, like the passionate music and dance of flamenco, can move European agriculture forward and free rural areas from today’s subordinating schemes.

The solutions are there, in el campo. Mixed farming like the agropastoral systems of El Manzano, combined with on-farm food processing, territorially-integrated food systems, renewable energy, fair working arrangements, better rural housing and infrastructure, cooperation, and adapted digital transformations can, all together, make rural areas alive again. There is not a silver bullet solution. And many farmers and consumers in Granada are aware of this and acting in this progressive socio-ecological direction, be it in the form of agroecological cooperatives like Valle & Vega, informal consumer-producers groups, or individual agroecological farmers’ initiatives.

I truly hope to return again to this wonderful corner of rural Europe. Until then, without a system change, I ask myself: will Cortijo El Manzano continue its long history in the Andalusian countryside, or become another rural memory, a ‘reliquia rurale’? Or will it be transformed into something new: a goat, an apple tree, a drone? Who knows. Probably, the answer is not “blowin’ in the wind”, but in the power and motion of flamenco and Andalusian history, still to be written.

Download this three-part series as a PDF

More letters from the farm

Letter From The Farm | A Flamenco Approach to Rural Resilience

Letter From The Farm | Cooking With The Lights Off – Ingredients of Rural Resilience

Letter From The Farm | Learning from a Campesino Family in Cuba

Farm to Forms – the Epicness of Trying to Establish and Run a Farm in France

Letter From The Farm | Restoring Nature, Improving Productivity

Letter From The Farm | The More-Than-Human Magic of Transhumance