What happens when a farm invites the wider community to collectively tease out its future? In September ARC2020 visited Brittany to find out.

La Ferme des 7 chemins is a dairy farm that’s been involved with Nos Campagnes en Resilience since the early days of the project. The farm is run by a three-member cooperative that makes decisions collectively and plays an active role in the local community.

When they found themselves at a crossroads in the development of the farm, they sought guidance in a process of collective reflection, bringing in an eclectic gathering of rural stakeholders and voices from across the food supply chain. Seed savers, farm workers and chefs sat down with elected officials and representatives of regional organisations to share insights and listen to each other’s experiences. Louise Kelleher reports.

When we called to say we were running late, we were offered pancakes.

Welcome to La Ferme des 7 chemins, a collective dairy farm in France’s Pays de la Loire that’s a case study in new models of rural resilience – and proudly Breton to boot.

Cédric Briand – one of three associates of the cooperative that runs the farm – is standing over a pancake griddle in the farm office. He’s cooking traditional Breton galettes for ARC2020: three of us have just come down that morning from Brussels to join the rest of the Nos Campagnes en Resilience team, who have been here the past few days helping the farm to set up for the event.

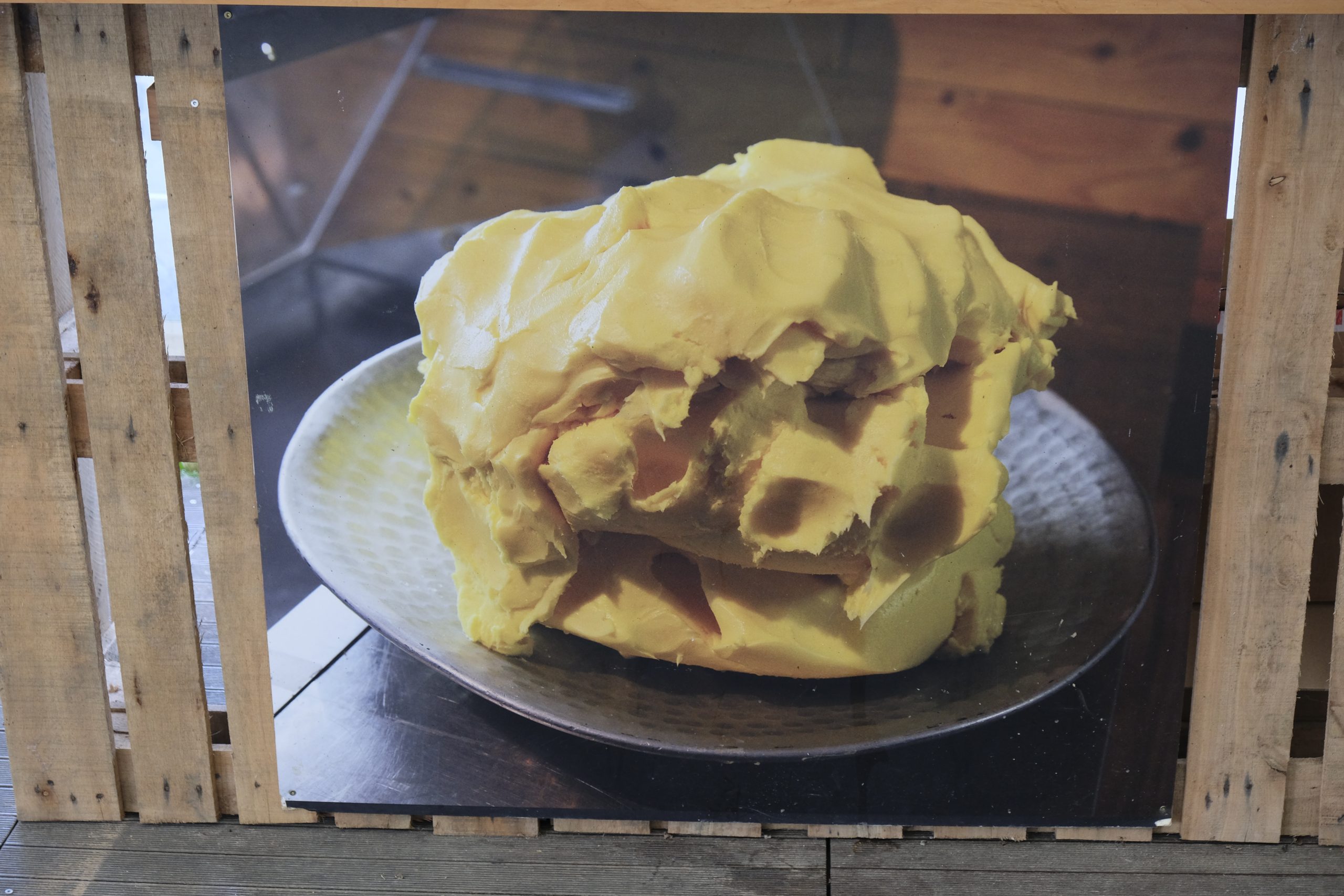

The little office is a busy spot. Participants pop in and out. Cédric fields questions from left and right as he reaches for ingredients, keeping one eye on the pan. Butter sizzles. It was made in the little dairy we can see out the window, right by the cheese cellar. A galette hits the pan. Made locally by a friend of the farm, this sturdy buckwheat flour pancake is nothing like its cousin the crepe. As luck would have it, a galette turns out to be the perfect vehicle for two hefty slices of Vacheron – Cédric’s latest creation from the cheese cellar.

Cédric tells us about his raw milk cheeses as he elegantly pivots from pan to table, where he’s laid out a mouthwatering selection. Cheeses are his speciality. In the cooperative each of the associates has their own area of responsibility but is hands-on with all aspects of the farm – livestock, arable production and dairy. This means Cédric is well-placed to answer our questions, of which we have many: about their cheeses, their milk, their cows, how their cooperative setup works, working conditions, CAP supports.

But back to the Vacheron. It’s a soft cheese with a cracked cappuccino crust and a gorgeous buttermilk yellow interior that quickly coats the warm galette. Cédric cracks a farm fresh egg on top, adds a shake of white pepper, then folds the edges into a neat square that frames the sunset yellow of the runny yolk. I’m the first to be served. I do as I’m told and sit down to eat.

Eclectic gathering

In the afterglow of the galettes we make our way to the barn. The main reason we’re on the farm today is to join an eclectic gathering of rural stakeholders for a series of thematic workshops and discussions. Along with two dozen farmers and farm workers, seed savers, chefs, elected officials and representatives of regional organizations, we will collectively tease out the future of the farm.

The farm has invited us all here with the support of the Université des Sciences et des Pratiques Gastronomiques (whose president Xavier Hamon does an excellent job of facilitating), the Slow Food Chefs Alliance (whose cuisine we feast on that evening), and a helping hand from ARC2020 (organising, networking and wiping down 30 dirty chairs).

Despite some thorny issues on the agenda, the circle is a friendly place. Jokes volley back and forth. Difficult life stories are shared to empathetic ears.

Our task as participants is to share our ideas, suggestions and questionings in a discussion of rural development issues as they relate to La Ferme des 7 chemins. We settle in among the hay bales.

The impressive Pie Noir Bretonne cows – the local heritage breed that is the pride of the farm – wander around the farmyard, hardly sparing us a glance. As we are introduced to the cooperative and hear about the challenges and skill sets on the farm, we hear the occasional assenting moo from the calves next door.

The workshops cover some key themes for the farm:

- Ties between the animal and plant worlds,

- Different skill sets coming together in a rural project,

- La Ferme des 7 chemins in local community life.

Before we dive into the workshops, we talk about how the cooperative’s way of farming is a sort of unsung activism. To escape the “corporatist paradigm” we need less talking and more acting. We need to get out of our comfort zones, takes risks, cooperate.

Workshop 1 – Where animal and plant worlds come together

The need for cooperation is underscored by the first workshop on the ties between the animal and plant worlds. In his presentation, seed saver Emmanuel Antoine, co-founder of Graines de liberté – Hadoù Ar Frankiz, points out that seeds are our collective responsibility. In Graines de liberté, market gardeners, plant nurseries, chefs and more come together with seeds savers to do this work.

Professionalising

The Bayer-Monsanto merger was a rare occasion to mobilise around a food-related issue. But activism and advocacy is no longer enough; the work of the small-scale seed producers must be a viable job. We need professional seed producers.

The COVID crisis has exposed issues around production. The market won’t change the model; now it’s time to mobilise funds to be able to produce seeds at scale and meet growing demand.

The business model is to value labour; the goal is autonomy. It’s time to professionalise and concentrate on ramping up skills. These issues are urgent. Yet we must take our time.

No livestock, no horticulture

Graines de liberté aims to get a simple message across: without livestock there is no horticulture in the long term. The organisation’s work lies at the interface between the animal and plant worlds.

After Emmanuel’s presentation the discussion turns to F1 hybrid seeds, and the cognitive dissonance around them in horticulture. There is now the potential (since the COVID crisis, which brought about a change in mindsets) to bridge the gap between horticulture and seed production. On the farm, a concrete example of how to bridge the financial gap has been the CAP payments for endangered breeds.

At European level, bridging the gap between farmer and seed saver is a political hot potato. However the new EU organic regulation is an opportunity to put in place the infrastructure for an organic seed market.

A similar divide exists between chefs and seed producers, with no mention of these issues in chef training.

Bridging gaps, working together – Workshop 2

Bridging gaps was the topic of the second workshop, with a focus on how different skill sets can come together in a rural project. Determined to redefine his profession, chef Antoine Chépy opened a non-profit restaurant in the French Basque country. Antoine described the surprised reactions of his colleagues when he decided to source his produce ultra-locally – from the market across the road. The produce sellers were equally taken aback as this is far from the norm in the hospitality industry.

Over his career Antoine Chépy has run several restaurants, but never been able to pay himself a wage. The non-profit model gives him more freedom. (A parallel here with the first workshop, when Emmanuel noted that seed production is more a vocation than a profession.)

After he was forced to close the doors of his restaurant, Antoine found work in horticulture. It was a culture shock. He was appalled to discover, for example, that the Protected Designation of Origin label (known as AOP in France) is associated with monocultures, elitism and homogenization of practices.

What is a fair price?

But Antoine’s heart was in promoting access to food (affordable prices). His vision was to reimagine food culture. And so, with the support of his peers, he opened a non-profit auberge – more low-key than a restaurant, with buffet style service to keep costs down.

He committed to paying a decent wage to every one of his staff (€12 an hour, almost €2 more than France’s minimum wage).

What is a fair price? He wanted to thrash out the question. Prices can’t be set by the market, he insists.

You take charge of what you eat

Antoine has always wanted to redefine his profession, and so he loves the fact that other chefs frequent the auberge. With the buffet set-up, he tells his customers: “You take charge of what you eat.”

Lots of his customers are local farmers. Often in poor health due to their working conditions, they’re surprised to find so many vegetables on their plates. But they get a kick out of knowing the producers of every item on the menu. He has a chance to build relationships with his regular customers and tell them more about what he does differently.

It’s a place to share knowledge and know-how. For example, saving grease from meat is almost a lost art. These traditional skills are often safeguarded by women (another parallel with seed saving).

Cultural shift

La Ferme des 7 Chemins asks that its restaurants commit to buying the full range of produce from the farm. “You can’t just order 10kg of butter. That would upset the whole production,” explains Cédric. It’s a frustrating reality for supplier and buyer alike. One workaround is for restaurants to stop using butter and cream altogether, and as a consequence, perhaps take cakes and pastries off the dessert menu. It’s a cultural shift.

Transfer of skills is important for La Ferme des 7 chemins. It’s the opposite of a “turnkey” farm. There’s a need to re-imagine things, to innovate. But they lack manpower.

The farm in local community life – workshop 3

The third workshop, on the farm’s ties to the local community, begins with a presentation by Xavier Hamon. He’s co-founder of the Redon Sustainable Food Consortium, a fledgling local food initiative.

If you can feed yourself, you can free yourself – and the Consortium maintains that ultra-local supply chains are the freest of all.

Conceived as an alternative to France’s problematic Chamber of Agriculture (an institution sorely lacking in sustainable solutions), the Sustainable Food Consortium is a “tool for all trades”. Inspired by the festival atmosphere and openness of discussion forums at the Nantes Cattle Festival Pas bête la fête, it prides itself on its openness to actors from across the supply chain, from seed savers to farmers to chefs.

But on the day we met Xavier, they had just had some bad news.

It’s an emergency; we have to be ambitious

The Sustainable Food Consortium needed two things: funding, and freedom. Not charity, noted Xavier.

Two days previously they had found out that the hoped-for funding was not forthcoming. This funding was indispensable to pay for staff to get the project off the ground. The reason the local authorities turned down the application is telling: the Chamber of Agriculture wasn’t part of the project; neither was the agro-industry. It seems the Sustainable Food Consortium was too bottom-up.

But, as Xavier points out, the job of the local authorities is to provide for the common good – and that has to include food and farming! It’s an emergency; we have to be ambitious.

Melting pot

Xavier’s eulogy for the Sustainable Food Consortium was followed by a presentation from Gérald Martin, coordinator of a performing arts collective called A LA ZIM ! MUZIK. The collective is on a mission to bring culture to where you live. Its shows are rooted in place: for example, a cheese tasting is always part of their concerts at La Ferme des 7 Chemins.

Their on-farm concerts are a melting pot of local residents; they seek to attract as broad an audience as possible.

The collective pays its performers, and makes a point of valuing its workers (a theme discussed in the previous workshop). It has the financial capacity to hire technicians.

Gérald notes a parallel between music and seed saving: just as seed savers are bringing back “old” varieties, his collective is reviving “old” songs that then become contemporary.

What are the benefits of cultural events for the farm, and to the local area? Apart from PR (events help to put the farm on the map) they make the arts accessible for rural residents. Another dimension is that the artistes and the farm have complementary approaches to their work in bringing together a range of skill sets.

Interestingly, these complementary approaches are being recognised by the local council, which now incorporates a cultural dimension in every new project.

Learnings from the day

The workshops and discussion were followed by a farm tour. Then it was time to wrap up the afternoon of workshops with a summary of the event.

ARC2020 president Hannes Lorenzen was invited to share some final thoughts. He identified several factors in the success of the project: the farm’s collective approach, cooperation, and good feel for business, and elements of transition. Urgent was a key word of the day, such as in the case of seeds – a symbolic example. There’s a whole discussion to be had around the complementary role of livestock farming, horticulture, etc. ARC2020’s question is: “How are we doing socially?” Other links in the food supply chain need to be brought in, such as farmer bakeries.

Learnings

The organisers of the day presented a summary of the workshops and discussion.

- Who should the farm be developed with, and how? How will it benefit the local area?

- Interdependence: urgent need to escape our “corporatist” culture.

- NB: no mention of the consumer during the event

- Infrastructures for training skill sharing are not fit for purpose

- What is a fair price? Acceptable for the market, or acceptable for decent standards of living? What should be factored into a fair price?

- Empathy towards others (and their obligations/constraints)

- Land is not just an issue in farming (e.g. hospitality sector)

- Culture of precarity

- Moving at different paces, different levels of awareness

- Complementary approach, which implies a shared moral responsibility (citizens, collectivities, elected representatives)

- Effectiveness is a concern (capacity to organise events on the farm) – is it sustainable? Do we have energy left for our personal lives?

- Unsung activism (the product speaks for itself – our project speaks for itself)

- Now is the time to be ambitious: “We have to move fast but not too fast”

Farm to fork dinner

For the evening we were joined by the farmers’ families and other guests in the barn for a wrap-up of the day’s workshops and discussion. Then it was time for a glass of wine, generous cheese platters, and a farm-to-fork buffet prepared by the Slow Food Chefs Alliance (Xavier Hamon was joined in the kitchen by Antoine Chépy and colleagues).

The restaurant resistance

One lesson from the workshops was that the “restaurant resistance” is taking on the “corporatist paradigm”. That’s why the Slow Food Chefs Alliance insists on meeting all of its producers in person.

The chefs treated us to a five-course taster menu featuring products from the farm. All local and sustainable, the menu was a balance of animal- and plant-based ingredients.

Pulses – often the poor cousin in French cuisine – were the star of the show in a delicious vegetable soup. “Cheap cuts” of beef were braised to perfection with potimarron squash and hazelnuts.

Gwell is a traditional fermented milk made in Brittany from the raw milk of Pie Noir Bretonne, the local heritage breed of dairy cow that is the pride of La Ferme des 7 Chemins. The slow food chefs honoured the simple yet nourishing fare of Breton grandmothers with a dish of Gwell served with boiled potatoes and buckwheat.

Acts of unsung activism

Every dish an act of unsung activism, the slow food chefs brought the concept of farm to fork to life. This unsung activism is a key theme of the day – and every day at La Ferme des 7 Chemins. Case in point: Cédric the cheesemaker frying up galettes for us (as well as another example of complementary skills coming together).

There was nothing pretentious about this slow food dinner, equally enjoyed by the farm labourers and the local mayor, who mingled easily with the other participants. We savoured every thoughtfully prepared bite. There was no dessert; just a sweet sense of people building bridges – between their different day-to-day realities, between the links in the food chain, and between the local and the European. Which is very much ARC2020’s raison d’être in France.

Our project speaks for itself. The themes of the day’s frank and fruitful discussions came together in an evening of dissolving differences over sustainable local food and wine. Another act of unsung activism.

It left us with a taste for weaving ties between farms and communities, at local and European level.

In the words of Mathieu Hamon, another associate of La Ferme des 7 Chemins, if we are to tackle urgent issues: “We have to move fast but not too fast”. We can build rural resilience together, one act of unsung activism at a time.

Nos Campagnes En Résilience is ARC2020’s project to help build rural resilience in France. Visit the project page here and follow us on Instagram, LinkedIn and Facebook. If you’d like to get involved, contact our project coordinator Valérie Geslin.

More on rural resilience

A Rural Proofed CAP post 2020? – Analysis of the European Parliament’s Position

Western Balkans | Balkan Rural Parliament Adopts Declaration

Rural Dialogues | Intergenerational Collaboration in the Vineyards of Southern France

AgTechTakeback | L’Atelier Paysan on Self-Build Communities in Farming

2 Trackbacks / Pingbacks

Comments are closed.