A father and son team allege shoddy pesticide disposal practices from the past are implicated in their respective cancers. In an English language exclusive, Peter Crosskey gives us the story so far.

![Base map by Llywelyn2000 (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.arc2020.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/500px-264px-glomel-featured.png)

Father and son Raymond and Noël Pouliquen are struggling to get their respective cancers recognised as occupational illnesses. Both have been drivers for Agricoop Bretagne, which is now part of Triskalia, Brittany’s largest farm-to-fork agricultural cooperative.

With 2015 sales worth two billion euros, the cooperative is owned by 18,000 farmers, employing more than 4,000 staff in a range of processing, manufacturing and retail subsidiaries.

On its website, the cooperative’s corporate video paints an idealised picture of its activities in a landscape that the members genuinely care about. The website tells us that the cooperative’s ambition: “…is to promote modern agriculture, reconciling productivity and environmental protection.”

It is a landscape with all the latest gadgets: in another video, a drone is used to map the weed-infested parts of a field. The survey results are fed into a GPS-controlled spraying system which only sprays the weedy areas of the field. So yes, less herbicide is used, but the carbon footprint of a high tech spraying strategy suggests that it is no more sustainable than what preceded it.

Like most other agricultural cooperatives of this size, Triskalia supplies its members with crop products, taking back empty pesticide packaging as part of the service. The Pouliquens were just two of the workers who handled empty packaging returns: Raymond from 1979 and Noël from 1989. Raymond was diagnosed with leukemia in 1999: Noël suffered a range of symptoms from 1996 onwards, was exempted from handling pesticide packaging collections in 2002 and was diagnosed with a lymphoma in August 2015.

The Pouliquens were not alone in suffering ill health after handling pesticide packaging returns on the site at Glomel in central Brittany. Of 10 other core workers employed there in 1992, five died before reaching 70 (four died of cancers); four are seriously ill with cancers and one suffers a chronic illness. Nor have the problems been limited to Triskalia premises: a farmer suffered ill health and lost livestock after a nearby Triskalia site burnt a batch of 500 kilo [dressed] seed sacks and fertiliser bags on an open bonfire.

For years, the Pouliquens claim, basic safety standards were flouted at Glomel. Between 1986 and 2003 the working week ended with a bonfire to burn off out-of-date stock, damaged packs, palettes, plastics, unrinsed containers. Raymond and Noël also claim that waste liquids were tipped out on open ground, including unsaleable and banned products. From 2003 to 2010 the same work was carried out by contract workers behind tarpaulins. Since 2010, the work has been outsourced. On one occasion, students on work placement were set to work compressing and baling empty plastic containers that splashed the unwary as the packaging was squashed.

And for years, farmers have been able to return empty crop treatment packaging to their nearest Triskalia shop, to be collected on Transena trucks. The Pouliquens both say there have been lapses in cleaning regimes for the vehicles and the rinsing of empty packaging has not always been thorough.

Agricultural crop products accounted for 12% of Triskalia’s total sales in 2015, which came to two billion euros. In 2015, Triskalia recovered no less than 88 tonnes of empty crop product packaging: more than a tonne and a half a week, when averaged out over a year.

The volume of toxic products stored and handled on the site means that it has a high tier Seveso 3 rating alongside major industrial plants in the region. The Seveso 3 directive assesses risk on the basis of the chemicals held at a site and the potential power of any reactions between them which could occur in the event of an incident. It requires constant monitoring of stock levels and also prescribes labelling and packaging standards. The Seveso 3 directive is primarily a risk management tool, leaving safety regulations to member states.

Industrial safety in France is overseen by regional authorities, through a regional agency, the Direction Régionale de l’Environnement, de l’Aménagement et du Logement (DREAL). The DREAL Bretagne website has a collection of working documents concerning the Distrivert (Triskalia-owned subsidiary) site at Glomel. One dates back to a meeting held in November 2007 and was addressed by the mayor of Glomel, who concluded that the site: “…does not present major hazards.”

A member of the management team pointed out the the site was purely a storage facility and had none of the risks associated with processes or mixing. He added that the site was authorised to store up to 1,300 tonnes of crop products, although: “…stocks are usually around 700 tonnes.”

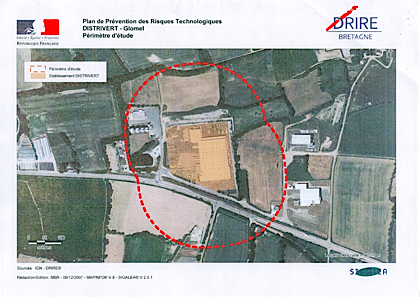

So, from a map approved at the time, it would appear that town and country planning restrictions for a site stocking hundreds of tonnes of dangerous products are limited to an area just over 500 metres west to east by about 750 metres north to south. The red dotted line delimiting the risk assessment area for planning restrictions passes in front of a food factory and includes half a kilometre of the RN164 main road to the port of Brest, which passes in front of the site.

So, from a map approved at the time, it would appear that town and country planning restrictions for a site stocking hundreds of tonnes of dangerous products are limited to an area just over 500 metres west to east by about 750 metres north to south. The red dotted line delimiting the risk assessment area for planning restrictions passes in front of a food factory and includes half a kilometre of the RN164 main road to the port of Brest, which passes in front of the site.

The DREAL documents record a number of spot checks on the site in the past decade, but the Pouliquens remain critical of the long term mismanagement of toxic products at Glomel and elsewhere in the group. Raymond recalls the smells arising from leaking and punctured packaging, as well as the fact that if suppliers refused to take back withdrawn or damaged products, these would be worked into the routine bonfires used to clear broken pallets, plastics and combustible rubbish at the site.

Noël recalls having health problems from 1997 onwards: symptoms included red patches on the legs, rashes on the face, irritation of the throat and nose bleeds, as well as persistent headaches. His colleagues suffered similar symptoms, while managers refused to acknowledge that there was anything dangerous in the workplace. It was not until 2002 that he was exempted from handling pesticides, although he still found himself handling packaging returns from time to time, until he was hospitalised in August 2015.

The Pouliquens are not alone in their experiences: warehouse staff at Glomel and other sites in the group have had similar careers, handling toxic products in leaky packaging without protective clothing. Raymond and Noël, however, are breaking the conspiracy of silence that shrouds agrichemicals in France. Download their press statement here (in French only).

• Phyto-Victimes, a French campaign for victims of crop treatments has launched a 45-day fundraising drive to support its efforts for those whose working lives have been blighted by crop products: visit this link for more information.

More

All ARC2020 articles on pesticides

France | Pesticide ‘Probation’ Sees Tensions Rise