Agroforestry is positively highlighted in many adopted texts and directives from Brussels and is also mentioned in the framework of the CAP and proposed as a possible measure of the Eco-Schemes. Despite its undisputed benefits, it is still largely unknown. What’s more surprising is that the current process of CAP strategic plans seems to virtually overlook it – so is it all spin, no substance? Andrea Beste has more.

In the last 10 years agroforestry has been described as a sustainable practice or recommended as an eligible activity in more than 20 EU-Commission strategies, parliamentary resolutions and EU-regulations. It is found in the Green Deal – the flagship-vision of the Commission for the next 50 years as to say in the Biodiversity Strategy and in the Farm to Fork Strategy. But you could also find it in the regulations on direct payments and rural development of the last EU Agropolicy (CAP 2013-2020) [i], and in the new post-2020 (2022) CAP. At least the term has even reached the Commission’s “List of potential agricultural practices that Eco-Schemes could support” in the new “strategic plans” (SP) that Member States (MS) will have to implement after the rules of the post-2022 CAP.

Agro-What?

Agroforestry is a combination of trees and grassland or trees and cropland. According to the FAO, ‘Agroforestry’ is a collective name for land-use systems and technologies where woody perennials (trees, shrubs, palms, bamboos, etc.) are deliberately used on the same land-management units as agricultural crops and/or animals, in some form of spatial arrangement or temporal sequence [ii]. The result is an ecologically and economically profitable interaction[iii]. Agroforestry systems range from grazing livestock under orchards to rows of trees in fields or forest gardens with interspersed trees and shrubs. Agroforestry is a promising land management system that can improve farmers’ livelihoods while reducing pressure on forests. It has positive effects on biodiversity and pest control and provides many tree-related ecosystem services such as increased soil fertility and improved water management. It also contributes to reduced erosion and carbon sequestration[iv].

Agroforestry synergies

A specific feature of agroforestry is its synergy effect – the combination of several components and their dynamic interaction – which increases the overall productivity of the system. INRA researchers have showed that the production from one hectare of a walnut/wheat mix is the same as for 1.4 hectares with trees and crops separated [v]. One way to measure the productivity of an agroforestry system is by using the Land Equivalent Ratio (LER), which compares the yields from growing two or more components (e.g. crops, trees, animals) together with yields from growing the same components individually [vi].

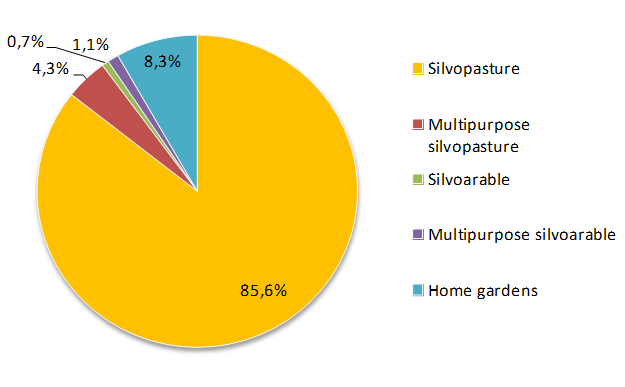

Nevertheless in Europe, few concrete support models have been developed in the member states so far. There are currently around 20 million hectares of agroforestry in the EU, equivalent to almost 12 % of the utilised agricultural area, which on the one hand is not so little, compared to organic area, which is 8.5 %. But knowing that potentially close to 90% of the European grassland area could include silvopasture practices and more than 99% of the European arable land would be suitable for silvoarable practices (regardless of whether organic managed or not), according to EU agroforestry association EURAF, that is not really much [vii].

For many people working in the agricultural sector in administration and advisory services, it still seems to be an alien word and concept. The exception is in some regions of the Mediterranean countries, where agroforestry systems have been continuously practiced.

With the modernisation and intensification of EU agricultural production and forestry since the 1960s, many traditional agroforestry systems practiced have been abandoned. For example, bocages (pastureland featuring a network of hedgerows) created over the centuries have given way to large fields as hedgerows were pulled out. Prominent examples still today are sheep grazing beneath cork oaks (in montados and dehesas found in certain parts of Portugal and Spain), or tall fruit trees under which crops are grown or livestock grazed (“Streuobst” in central Europe).

This recent history of loss means the term is not very familiar in the administration of the MS – a big job of re-learning is needed, especially when devising national funding programmes.

Where did the Agroforestry go?

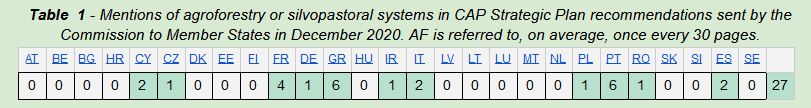

Just before the end of 2020, the European Commission published EU-wide and 27 country-specific recommendations directed to the national authorities. The 27 Staff Working Documents contain an in-depth analysis of the challenges faced by agriculture, forestry and rural areas in the MS, as well as a list of non-binding recommendations to design ambitious CAP Strategic Plans in line with the Green Deal objectives.

However agroforestry is completely missing from the Commission’s recommendations to 16 member states [viii] (meanwhile, it’s sibling ‘agroecology‘ is also missing from 21 national recommendations, despite also being a keyword used in the Green Deal).

Whereas the commission is – as often – good in rhetorically pointing out the key factors in this recommendations:

– Intensive agriculture is a problem. This was stressed in many analyses conducted across the Member States. An impressive body of data and scientific references on the negative socio-economic and environmental implications of intensive livestock, pesticide and fertiliser use, ploughing of permanent grasslands, farming on wetlands and peatlands, and more, were presented.

– Sustainable farming is a solution. Considering their multifunctional role in our society and planet, the Commission acknowledged that small scale farmers of any age and gender are disappearing, leaving food provisioning, land management, and landscape completely abandoned and in the hands of corporate farming and food industry interests.

The recommended solutions make you rub your eyes because you think you’ve missed something somewhere.

In many recommendations, digitalisation emerges as a systematic solution to all Member States to increase the sustainability of food and farming, as well as for the development of rural and forestry areas. Precision farming, however it may be defined, seems to be a kind of panacea for the pressing problems of climate change and biodiversity loss, while promising initiatives such as agroecology or agroforestry continue to be left out or not mentioned at all.

What has happened in the CAP Strategic Plans Process?

Recommendations had been discussed bilaterally between MS and Commission with the national governments before their publication. In the writing process, some adjustments were made, which for the most part weakened the potentially positive socio-ecological outcomes in a process the public did not have access to. The overall impression from a cross-comparison among the recommendations is that the Commission has made considerable efforts to make it as easy as possible for the Member States to incorporate any suggested changes.

This fits in with the whole process of developing the national Strategic Plans.

The process followed two phases.The first one (Phase I) was for diagnosis and needs analysis, and the second one (Phase II) on intervention strategy. As the Phase I including SWOT analysis is already completed in most MS, they are currently working on prioritizing needs, eco-schemes and reinforced conditionality. An earlier analysis shows that the development of the SP did not always involve all the relevant stakeholders, and there was also room for improvement in terms of transparency.

The design and approval of the future 27 CAP Strategic Plans are key moments to demonstrate the true commitment towards a fairer, greener, and rural-proofed CAP reform. The European Commissioner for Agriculture, Mr Wojciechowski, promised ‘full transparency’ and ‘open dialogue beyond DG AGRI and agri-ministers’.

It is clear that to achieve the European Green Deal objectives, the currently negotiated post-2022 CAP and the national SP would require serious revisions. Especially because the CAP is missing the central elements of an emissions reduction target for the agriculture sector and effective means to sanction climate- and environmentally-disruptive practices in agricultural activities.

The potential of agroforestry was highlighted by EU Agriculture Commissioner Janusz Wojicechowski in July 2021 during a press conference [ix]. Calling the link between the CAP and forest strategy “very important”, he championed agroforestry as an instrument to contribute to the forestry targets, highlighting that the new CAP will allow member states to support carbon farming and agroforestry via the new eco schemes instruments, as well as rural development measures.

It remains unclear how the Commission can expect member states to take up agroforestry practices in their national plans if it does not appear in the majority of the recommendations. Let’s keep looking to see if this will happen.

References

[i] Past CAP Pillar I has not promoted agroforestry in an adequate way, but this situation has been improved with the Omnibus regulation. Launched at the end of 2017 it has improved the measure 8.2 in those areas that already have agroforestry, as measure 8.2 can be used to improve already existing agroforestry and not only for new established lands.

[ii] http://www.fao.org/3/i9037en/I9037EN.pdf

[iii] https://euraf.isa.utl.pt/news/policybriefing10

[iv] UNCCD Science Policy Interface (2017): Sustainable land management contribution to successful land-based climate change adaption and mitigation.

[v] https://euraf.isa.utl.pt/sites/default/files/pub/docs/agroforestry_fact_sheet.pdf#overlay-context=media/brochures

[vi] http://www.fao.org/forestry/agroforestry/80338/en/

[vii] https://euraf.isa.utl.pt/action/policy/Agroforestry_in_the_past_CAP

[vii] https://euraf.isa.utl.pt/news/policybriefing10

[ix] Money does grow on trees, Euractiv, 16.07.2021

More

The Myth of Climate Smart Agriculture – Why Less Bad Isn’t Good

A Soil Scientist’s Perspective – Carbon Farming, CO2 Certification & Carbon Sequestration in Soil

Comparing Organic, Agroecological and Regenerative Farming part 2 – Agroecology

Letter From The Farm | Three Years In: Realism And Planning For Utopia

1 Trackback / Pingback

Comments are closed.