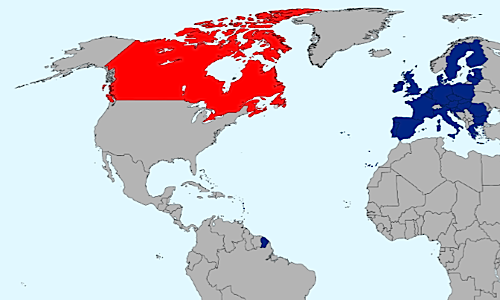

Non-government organisations on both sides of the Atlantic are restating their arguments against the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) between Canada and the European Union, which was signed on October 30. The race is on to prevent CETA from being ratified in the coming months. In the first section of a two-part report from the Paris leg of a CETA and TTIP European Tour by experts, ARC2020 looks at the warnings given by the Council of Canadians. The second part will cover wider transatlantic issues that have been packaged as trade questions, but in reality go far beyond their stated aims.

Although signed on the 30th October in Brussels at the 16th EU-Canada summit, there is still a chance that one or more national governments could block CETA and challenge the basis upon which it is founded. But to achieve this will require civil society to mobilise across Europe and Canada with a clear message to reject years of corporate scheming behind closed doors.

Trade campaigner Sujata Dey, from the Council of Canadians, and legal expert Sharon Treat from the US-based Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy (IATP) undertook a whistlestop tour of Europe in December to meet NGOs and policymakers across the continent. Their tough schedule took them to Belgium, Germany, Hungary, France, Slovenia and Poland.

ARC2020 caught up with them in Paris, where they spoke at the Assemblée Nationale in a meeting hosted by the veteran environmentalist Jean-Paul Chanteguet. The parliamentarian was in no doubt as to the damage that CETA would do to democracy on both sides of the Atlantic. Should CETA be ratified in its current form, he warned, it will grant corporations the power to sue national governments in WTO-regulated courts for passing laws that supposedly damage a foreign investor’s interests in the host country.

Known as the Investment Court System (ICS), CETA would allow corporate interests to challenge democratically-elected governments in areas such as environmental, health or employment regulations. If the ICS mechanism sounds familiar, it should do, since it is basically a new name for investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS). Just like ISDS before it, the ICS process is a one-way street, since it is not available to national governments to seek redress for corporate abuses of any description.

“Everybody thinks that Canada is full of family farms and that its agriculture is somehow more wholesome than the US, but I can assure you that’s not true,” says Sujata Dey. It is a point that she has to make again and again to the people she meets in Europe.

“Everybody thinks that Canada is full of family farms and that its agriculture is somehow more wholesome than the US, but I can assure you that’s not true,” says Sujata Dey. It is a point that she has to make again and again to the people she meets in Europe.

She has lost count of how many times her work as a trade campaigner for the Council of Canadians has brought her to Europe this year now that CETA’s machinations have been hauled into the harsh light of day. “So many people are just glad we’re not Americans that it takes a while for the message to sink in,” Sujata explains.

Since the 1970s, Canada has lost 45% of its farms through consolidation: today only one in 20 farms has an income of more than one million Canadian dollars (EUR 1.4 million), but farms in this bracket account for nearly half the country’s food production. Industrial livestock holdings are commonplace, with feedlots containing 20,000 or more head of cattle. Factory farms for pigs house between 5,000 and 20,000 animals, while poultry units cram anything up to 100,000 birds into their sheds.

Farm sizes are growing on both sides of the Atlantic. In 1991 the average Canadian farm was 400 hectares, by 2011 it was 424 hectares. In Europe, the average farm size soared from 14.4 hectares in 2010 to just over 16 hectares in the space of three years. The average French farm increased from 42 hectares in 2000 to 55 hectares in 2010.

Industrial farming has made the country’s agricultural markets into high volume, low margin endurance tests. Canada currently imports 7,000 tonnes of pigmeat, all of which is liable for duty. “It is a low-price market in which retail prices are 25% cheaper [than on comparable markets],” Dey explains. “Canadian pig producers are paid between 15% and 35% less [than their foreign counterparts].”

Livestock production is propped up by the liberal use of antibiotics and hormones, with no requirement for veterinary supervision. Beef and poultry killing lines operate with chlorine wash units as standard, in a bid to restrain the spread of bacteria. Despite conditions that would not be allowed in EU livestock production, the European Commission insists that European standards will not change.

Yet Canadian meat industry leaders are actively campaigning to gain acceptance for growth hormones and an easier regime for antibiotics on this side of the Atlantic. Sey cites Canadian Cattlemen’s Association president Dan Darling. He fully expects the Canadian government to fund expert witnesses who will defend his members’ interests and “eliminate the remaining non-tariff barriers to Canadian beef.”

Canadian animal welfare practices are based on legislation that dates back to 1892 and, with the exception of Quebec, animals are treated as goods rather than sentient creatures. Investigators discovered cases of unwanted chicks being ground up alive, with a similar culling treatment for hens taking several seconds. Animals can be transported across Canada for 52 hours without water or food in Canada, compared to 14 hours in the EU.

Upstream from the livestock sector, Canada is the world’s third largest producer of GM crops and biotech extends to apples and GM salmon. CETA’s chapter 25.1 contains an explicit commitment to reduce regulations on biotechnology. Article 2.2 of chapter 25 promotes the approval of “…efficient biotech products, based on scientific data.” This, coupled with an EU commitment to fast track Canadian proposals for (GM) oilseed rape does not bode well for a sustainable future.

Canada has already challenged EU regulations for crop treatments 21 times in the WTO, in addition to the long-running discontent over the European ban on the use of hormones in beef and pigmeat production. CETA offers no protection for European regulations, but is loaded with mechanisms such as ICS, equivalence and regulatory co-operation, all of which will strengthen the hand of lobbyists for transnational corporate agriculture.

The second part of this report will look at the broader aspects of transatlantic relations and how trade is being used as a cover for a very different agenda.

More

All ARC2020 articles on CETA and on TTIP