How does a rural community plan for the future when it is literally living below sea level? In this excerpt from the book “Rural Europe on the Move: A travel guide to transitions”, Hannes Lorenzen shares the story of his home island of Pellworm on Germany’s North Frisian coast, where the community has come together in the face of climate change, rising sea levels, and other threats to its survival.

After three decades of innovation, inventiveness and most of all community spirit, Pellworm can now boast renewable energy independence. The islanders are proud to share their experiences in the transition process with other islands and communities.

“Rural Europe on the Move: A travel guide to transitions” is published by Forum Synergies, an organisation which since its inception 25 years ago has identified and highlighted the potential of rural Europe. Gathering local communities, farmers, foresters, environmentalists, and political decision-makers from across the continent, the organisation has demonstrated and bolstered grassroots rural sustainability, arguing that separate from EU policy-making, individuals and groups across the continent are building sustainable, resilient rural futures of their own accord.

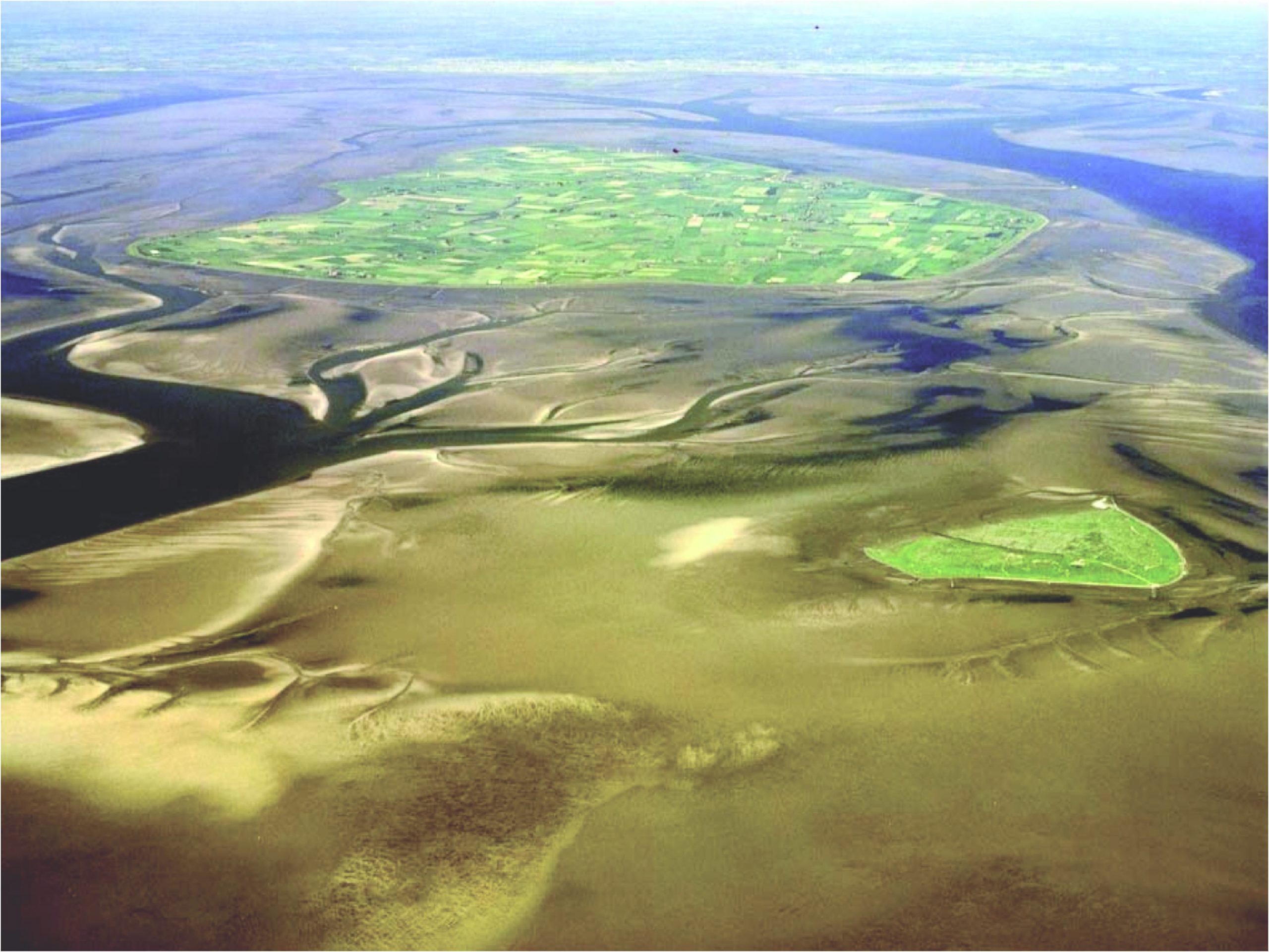

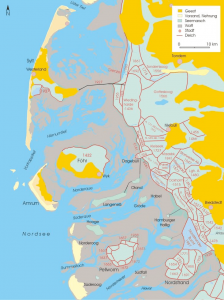

Lorenz, Flora and Alma sit in front of the colourful beehive on Hallig Süderoog eating potato soup. With our guide Knud Knudsen, we have just crossed the North Frisian tidal mud flats of the sea – barefoot. On the horizon, we can still see the skyline of Pellworm island like a thin pen between the sky and the mud flats.

With the tide withdrawing towards deeper parts of the North Sea, it took us one and a half hours to wade through black mud, tide gutters and fine white sand banks to get here, in the steady company of seagulls, terns, avocets, and oystercatchers – a lively and always excited company of sea birds.

The mud drying on our feet is as black as the bees leaving and entering their hive. Dark or Northern bees are an endangered species and currently mainly preserved in Norway we learn. They are part of Nele Wree’s and Holger Spreer’s ARK, a project for saving and regenerating endangered farm animals. Around the farmhouse toddle rare geese, ducks and colourful chickens. Sheep and cattle are quietly grazing in the salt meadows.

With their two year old daughter Fenja, the couple runs a 62 hectare organic island farm in the middle of the Wadden Sea National Park, – alone. “Our land is regularly flooded during winter storms,” says Nele. “The North Sea then may come licking at the threshold of our living room. But we still feel quite safe. The house was built on this little hill called ‘warft’, six metres above sea level. If the flood gets higher, then we step up to the rescue room on the first floor. The stables are a bit higher, so also the animals should be safe.”

ARK seems to be the right name for Nele’s and Holger’s brave enterprise to preserve genetic diversity in farming at such a remote place. They are part of a broader network of farmers and breeders who take care of farm animals that are in danger of being extinct in today’s more and more industrialised farming.

Living below sea level…?

Lorenz and his cousins listen amazed. I just met the youngsters between the ages of 11 and 15 on our low tide walk to Süderoog. They have come alone. “Our parents work in Berlin and Bremerhaven. We have been on Pellworm island for holidays since we are able to swim. That was the condition of our grandparents before agreeing to take care of us. We meet as big family with relatives here. We love this life of freedom in nature.”

They remind me of times not long after the second world war when Süderoog island, then owned by a German-Swedish couple, welcomed children of their age from across Europe to experience a life close to nature. You could call it an early European Erasmus programme. As a boy I was on the Hallig in 1964 and learned how to go fishing, make hay, milk cows, make butter and work with horses. It was fun speaking our imaginative language to understand each other. English was not ‘lingua franca’ at that time. Later, in the 1980s the Hallig was taken over by the federal state of Schleswig Holstein and became a nature reserve, a resting place for migrant birds passing in spring and autumn through the region.

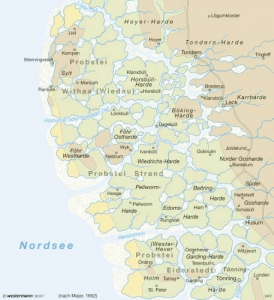

“Is it possible that an island like Pellworm lies a metre ‘below’ sea level?” Flora asks on our walk back to Pellworm. “Yes it is. Just imagine you put a light soup plate to swim on calm water surface,” I reply, “the water does not flow into the lower part. But if just a little wave of water would get over the rim, it immediately sinks. While Nele’s house is built on a warft six metres above sea level, the land of Pellworm island has been sinking over centuries and needed to be protected by dikes against floods. The dikes are now eight metres high. If Pellworm had no dikes all around, every six hours the North Sea tide would flood the plate. Pellworm and Süderoog are part of the small islands group left over from the big flood of 1634 when thousands of people died and the North Frisian coast was torn into small pieces. Like the Netherlands, with most of the land below sea level we need strong coastal protection, even more so with climate change and rising sea levels.”

We reach the dikes of Pellworm. Süderoog now is just a tiny mouse at the horizon. The tidal gutters are filling quickly, the tide is coming in. A long queue of sheep trot by. They are our lifeguards on duty, as they keep the grass short so that the roots get deep enough and the sea cannot easily tear holes in the dike. Behind the dikes we grab our bikes and say goodbye. Good to see youngsters who feel so attached to this remote place. “We love this life of freedom in nature” still resonates, when I cycle back to our farm.

Making change despite headwind

Biking on Pellworm, no matter which way you go, is a struggle against the wind. Maybe this climate has formed our stubborn Frisian DNA having to stand up against gusts and sea. It may therefore come as no surprise that in the late 1980s, when the Regional Government of Schleswig-Holstein suggested that the entire mud flat of the Wadden Sea should become a National Park, ‘No National Park – freedom for Frisians!’ stickers were found on every shop and car. Farmers and fishermen feared restrictions and mobilised against the government’s proposal.

For us, a group of islanders from all walks of life, this conflict was like an ‘energiser’ for a civic movement towards more sustainable island development. Just as seagulls take off best by running against the wind, we used the spirit of opposition against the regional authorities to prepare for marrying wildlife protection with sustainable farming and renewable energies. In 1989 we founded our non-profit organisation ‘Ökologisch Wirtschaften!’

We used the spirit of opposition against the regional authorities to prepare for marrying wildlife protection with sustainable farming and renewable energies

Ökologisch Wirtschaften! means ‘Ecological Economy!’. It carries the exclamation mark as a call to action and transition from rather unsustainable farming practices, depopulation and mainland dependence, towards a decent livelihood for all islanders gained from renewable energies, organic farming and soft on-farm tourism within a unique and vulnerable ecosystem.

We had support from many islanders and from our tourists. But the process of transformation was not a ride with backwind. In the beginning the mayor and local government saw us as troublemakers and dreamers, and they placed many hurdles and barriers to our ambitions. But stubborn as we are, we pushed on.

Pellworm discovers Europe

We needed allies to keep our ambitions afloat and we found them in Europe. In 1995, Ökologisch Wirtschaften! launched the European Network of Eco-Islands. We found partners with similar ambitions for transition on the islands of Hiiumaa (Estonia), Alonysos (Greece), Elba (Italy) and La Palma (Canaries). With support of Forum Synergies former president Isobel Holbourn we also established intensive contacts with the Scottish island of Foula. Isobel was a wildlife ranger on Foula and shared with us many ideas of improving relations between people and nature.

With Hiiumaa we had the strongest ties. We welcomed an Estonian family to share their experiences of rural tourism and converting to organic farming. We established the so-called ‘wool connection’ project. At that time the people of Hiiumaa were just free from their forced military security status during the Soviet Union, and Estonia was preparing to join the EU.

The ‘wool connection’ project became a civic pioneer for fair trade between islands. At that time, Pellworm farmers got almost nothing for their sheep wool. Hiiumaa had almost no sheep but it did have unused wool processing machinery. So we moved wool to Hiiumaa, the wool facilities were repaired and a group of country women started spinning and knitting sweaters, balaclavas and socks to be sent back to Pellworm. That’s how the ‘Pellover’ was born! It was not just work and added value for both islands, it became a story to illustrate how creating markets and income from cooperation and fair trade is possible. No government and no subsidies were needed for that, just a spirit of curiosity and cooperation between people.

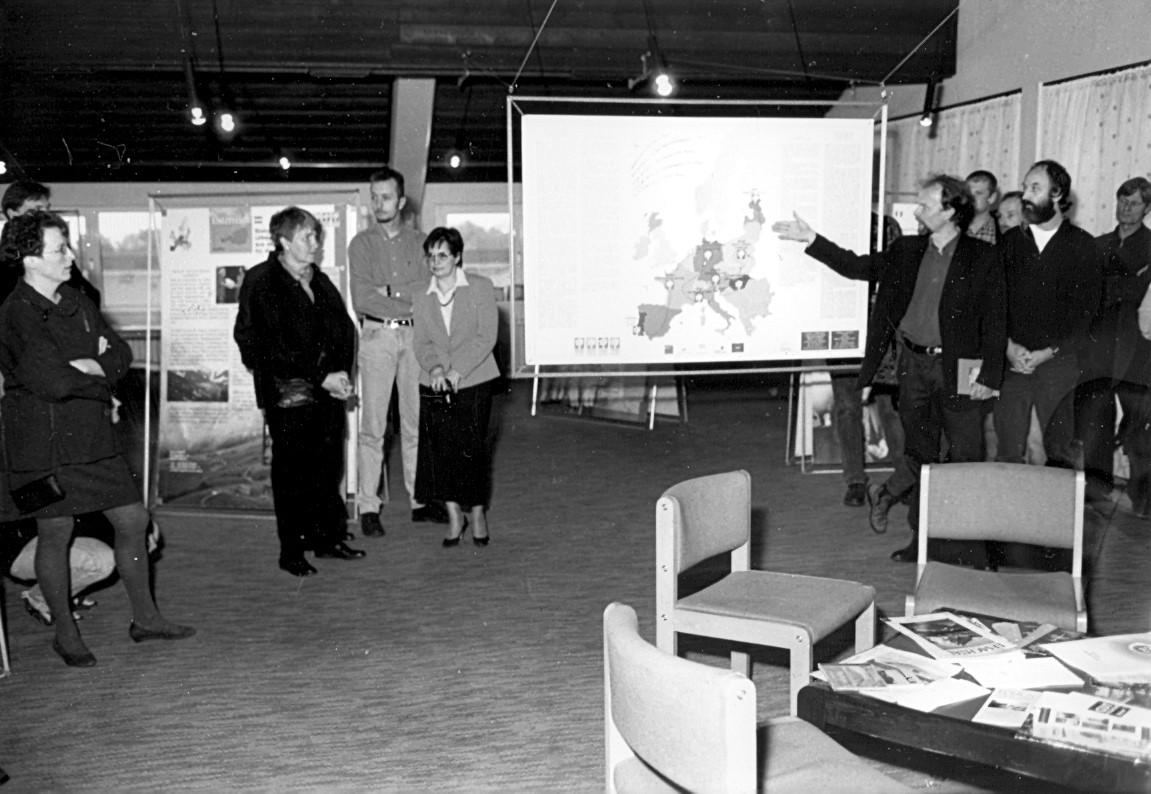

Is it a surprise that in 1996 Ökologisch Wirtschaften! also became a member of what was later called Forum Synergies? In 1998 Pellworm was also a stop of the travelling exhibition and events of the Sustainable Mystery Tour.

Transition needs time

Thirty years have now passed since we founded our island association. The fundamental changes our generation has achieved are clear. Pellworm now produces its own electricity from combined renewable sources – wind, sun and biogas. Wind turbines, solar panels and a biogas plant are owned by islanders, not mainland investors, so that the added value stays mainly within the local island economy. The number of wind turbines was strictly limited to avoid impact on the landscape. Pellworm today exports electricity to the mainland. It has become popular for our tourists to subscribe and consume Pellworm electricity at their homes in Hamburg or Berlin. German energy law makes this possible. Our local community energy project has attracted many visitors to learn about decentralised renewable energy systems.

Dr. Uwe Kurzke leads an energy working group which keeps up a dynamic process of integration of diverse renewable energy sources. “Maybe Ökologisch Wirtschaften! offered a home for the homeless,” says Uwe Kurzke, general practitioner on Pellworm island for more than 30 years. “A newcomer from the mainland like me or a local resident ready to step out of the row – makes no big difference when it comes to struggling against headwind. We were and still are in opposition to mainstream thinking, but we are also an innovative experimental hub. When we decided to use our local potential to become economically independent and stay close to nature, we stepped out of the widespread spirit of being disadvantaged.”

We were and still are in opposition to mainstream thinking, but we are also an innovative experimental hub.- Uwe Kurzke

Uwe Kurzke likes challenging business as usual. But he has also built bridges between the different ideological clans on the island, especially in the field of renewable energies and climate protection. “Cooperation between individual cells is the key for our health and survival as an organism. That is also true for our island community. In the past we had to build our dikes against the sea. Now we need community spirit to join forces and create a resilient island economy.”

Soil, plants, animals, humans – time to think in terms of ‘We’

In May 2018 we celebrate 30 years of Ökologisch Wirtschaften! with a week of farm visits and round tables – ‘fishbowl sessions’. Our themes focus on transition towards sustainable island farming. It is time to think beyond conventional and organic farming and to talk about common challenges. We have chosen the items soil, plants, animals, and our human relations with them. Part of our soils have suffered from the use of heavy machinery and monoculture; plants have become dependent on pesticides and artificial fertilisers; we start to realise that we have too many animals on the land regarding a balanced nutrient cycle; transport to the mainland for slaughter is too long. As stubborn islanders we often have a hard time talking to each other. We rather talk about others. It is time to think in terms of ‘We’.

The fishbowl session is a moderation technique often used by FS, especially during its big meetings, in order to bridge the ‘power-gap’ between local, national and European actors. It consists of an inner circle of participants actively involved in the discussion, which is surrounded by the wider audience. Participants from the outer circle can in turn move to the inner circle and get involved in the debate. The debate goes beyond the classical panel discussion and becomes participative. Additional rules of the game help to overcome the known patterns of conflicts, like an obligation for all participants to frame their contribution by constructive proposals: “I need support in…..” and “I can offer….”. Especially in political debates, such rules for constructive dialogue help to create a dynamic well beyond stereotyped statements, accusations and destructive rhetoric.

“We enjoy being islanders and we enjoy looking beyond the dikes into a future which needs change in our relations,” says the young navigator Tore Zetl. He looks forward to being the captain on Pellworm ferry soon, is married to a young woman from the French Drôme region and is a member of the steering group on future perspectives for Pellworm community. “Our parents have achieved a lot, but there is still much to do to keep our island community afloat to cope with the many challenges”, he says. His two brothers work as an organic farmer and a fisherman on the island.

Raising awareness of climate change

2018 is a very hot and dry summer. Some older islanders talk of the hottest and driest summer ever. There is very little grass for the cattle, the soil is deeply dried out and it is very difficult to gather winter silage or hay. Is this the result of climate change? Alongside rising sea levels, are we also facing regular drought? There are many unanswered questions and concerns at our round tables … and a high level of attention.

Thirty years ago, we had no clue what climate change meant. This year Silke and Jörg Backsen, organic farmers on the island, have joined a group of German mainland farmer plaintiffs of a court case against the German Federal Government, supported by Greenpeace. The accusation indicts “the Federal government’s inaction on climate change”. Their arguments have gained strong interest in the German public debate.

One of the guests at the round table of the fishbowl session is Bernhard Osterburg, special adviser to the German Federal Government at the Thünen Institut in Braunschweig working on adaptation of farming practices to climate change. “Pellworm would be the ideal place to experiment with practices for a climate-friendly farming on a small scale,” he says.

“Pellworm would be the ideal place to experiment with practices for a climate-friendly farming on a small scale”- Bernhard Osterburg

Osterburg suggests working on a full accounting of all nutrients, which circulate on the island, including imported feed, fertilisers as well as green, liquid and solid manure. That would lift our thinking above the fences of our individual farms. Based on this balance of nutrients we might be able to reconsider stocking density of animals, improved crop rotation, and better protection of soils against erosion and loss of humus. In 2019, we start this exercise and might have sufficient data to consider improved agronomic practices including conventional and organic farms. At the end of the day we sit on this soup plate island together.

Other participants at the round tables suggest work on breeding special organic and climate resistant seeds and farm animals and to become another ARK together with Süderoog. We could revitalise contacts with the European Small Islands Network (ESIN), which Camille is currently heading as president.

Knowledge sharing with Drôme in France

Jochen Haug from Die in the French Drôme region, visits Pellworm to share his experience of local slaughter options. He has founded a farmers’ cooperative in order to save a small slaughterhouse in his region that was about to be closed by the authorities. We discuss possibilities of mobile slaughter facilities on farms to avoid the long and exhausting transport of our cattle to the mainland.

All these reflections and suggestions could be the ingredients for what many on the island would like to see emerge in the future, namely ‘the Pellworm trade mark’. It could create a new common ground for all. It could become another ’Pellover‘ narrative of connecting within our local economy, between farmers, local restaurants, the school, the energy cooperative, the dairy, a new slaughterhouse … and friends across Europe.

I close the west doors of the barn and the farmhouse. A severe storm is announced. If it carries rain it would be welcome, but it turns out to just be violent wind with not a drop of water for our fields.

The Pellworm experience – in a nutshell

You do not need to live on an island below sea level to realise that climate change and rising sea levels will change your life. However, growing conflicts between ‘business as usual’ and endangered nature become more visible in a small and remote place like an island. Conflicts between humans and nature are more graspable and limitations of resources and business more costly.

Islanders are sceptical about solutions and investments imposed from outside and from above. But Ökologisch Wirtschaften! did not reject the idea of a national park, nor did the association use that idea just as an add-on to tourism. Members of the association try to turn perceived disadvantages into energy for change. Pellworm has now achieved renewable energy independence as a new economic pillar for many and the association proudly shares its experiences in this transition process with other islands and communities. Experimenting solutions for the future seems to be the key reaction to the growing challenges.

Ökologisch Wirtschaften! reached out to other European islands by launching the European Eco-Island Network and cooperating with other rural projects in Europe through Forum Synergies network. The island community is still going through high waves of successes and setbacks, economically, environmentally and in human relations.

We have learned to struggle and accept that there is not just one solution, but many. For a long time we have had to defend ourselves against the sea and we will have to do more to keep afloat. We need innovation and inventiveness but most of all a spirit of community. We are an aging population with a shrinking farming sector. Our local businesses are increasingly dependent on tourism. This is risky business because the tourist season is short, and infrastructure like school, medical care and social services needs a minimum of inhabitants to be economically viable. Pellworm is a good place to experiment the balance between survival and pioneership.

Download the full book Rural Europe on the Move: A travel guide to transitions

The book can also be ordered as a hard copy

More on rural Europe

Flagrant Vagueness | Commission Launches a Vision Without a Strategy

Western Balkans | Balkan Rural Parliament Adopts Declaration

Rural Semester as a Tool to Deliver a Truly Holistic Policy for Rural Areas

A Rural Vision is Good – A Strategy and Immediate Action is Better

A Rural Proofed CAP post 2020? – Analysis of the European Parliament’s Position