A number of organisations (Heinrich Boll Stiftung, Birdlife International Europe and Central Asia and Friends of the Earth Europe) have come together to publish an Agriculture Atlas. This is a really useful introduction to agri-food and rural policy in the EU. It focuses on how CAP is implemented, including through case studies from a number of EU member states. Below we republish the introduction.

by Christine Chemnitz and Christian Rehmer

Set in Brussels since the 1960s, the Common Agricultural Policy is one of the EU’s oldest policies. Despite its extensive funds and regular reforms every seven years, it is poorly attuned to the needs of Europe’s hugely diverse farm sector. Payments tied to area disproportionately benefit large, industrialized farms and promote productivity. Goals to minimize and adapt to climate change, protect the environment and promote rural development are poorly served.

Download the Agriculture Atlas: Agriculture Atlas 2019

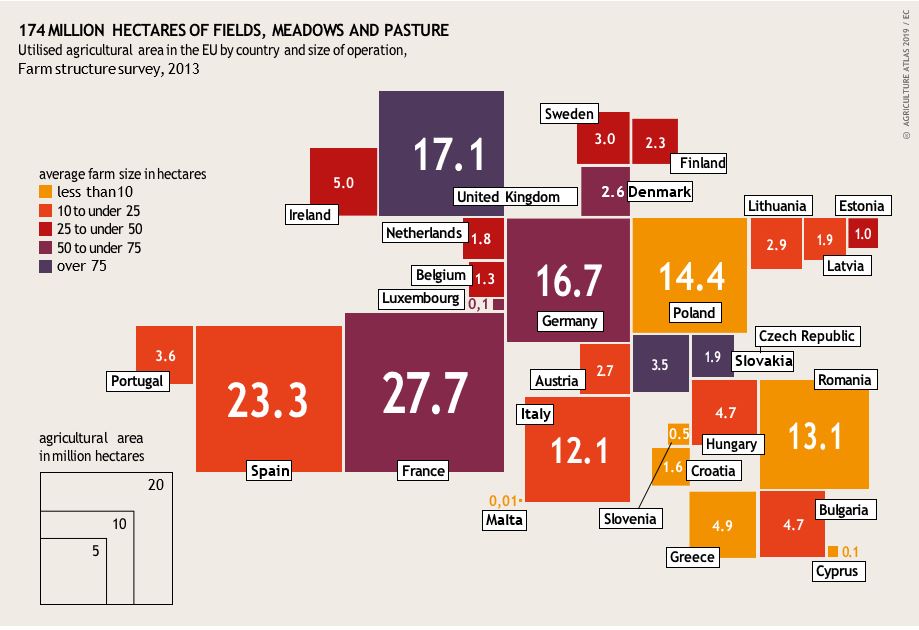

From Ireland’s placidly grazing sheep to France’s hillside vineyards, from the huge wheat fields in eastern Germany to the patchwork of tiny farms in Romania: agriculture covers 175 million hectares of Europe and shapes the landscape like no other activity. Diverse in every aspect, it has been influenced by ecology, culture and history, politics and economics, and, in return, affected by them. Cultural landscapes have emerged over centuries, reflecting the continent’s history.

The land is divided into over ten million farms; one-third of them are located in Romania alone, and another 13 percent in Poland, followed by Italy and Spain. Farm sizes vary widely, from an average of a little over three hectares in Romania to 133 hectares in the Czech Republic. Farming’s contribution to the economy also varies from one country to another. In 2017, for the European Union as a whole, it accounted for 1.4 percent of the gross domestic product. It exceeded three percent in many of the new eastern member states of the EU, but reached between 0.5 and one percent in the older western member states.

No other part of the economy is so deeply influenced by European Union rules as farming, which is subject to the Common Agricultural Policy, or CAP. The objectives and tasks of this set of rules were first laid down over 60 years ago, in 1957.

At that time, the European Economic Community (as the EU was called back then) had just six member countries. Its aim was to guarantee an adequate supply of food at reasonable prices for the population of post-war Europe. That meant promoting farm productivity, stabilizing markets by hindering big price fluctuations, and ensuring the farming population an acceptable standard of living. The Common Agricultural Policy quickly achieved these goals: by the 1970s, farmers were producing more food than Europe could consume. However, the attractiveness of guaranteed prices and incomes soon revealed their negative side: butter mountains towered up and milk lakes flooded over. Warehouses in which the EU stored the unsellable surpluses came to be a sure-fire source of income for their owners. Export subsidies artificially cut prices by dumping products on the world market, regardless of the ruinous effect on smallholder farmers in the importing countries.

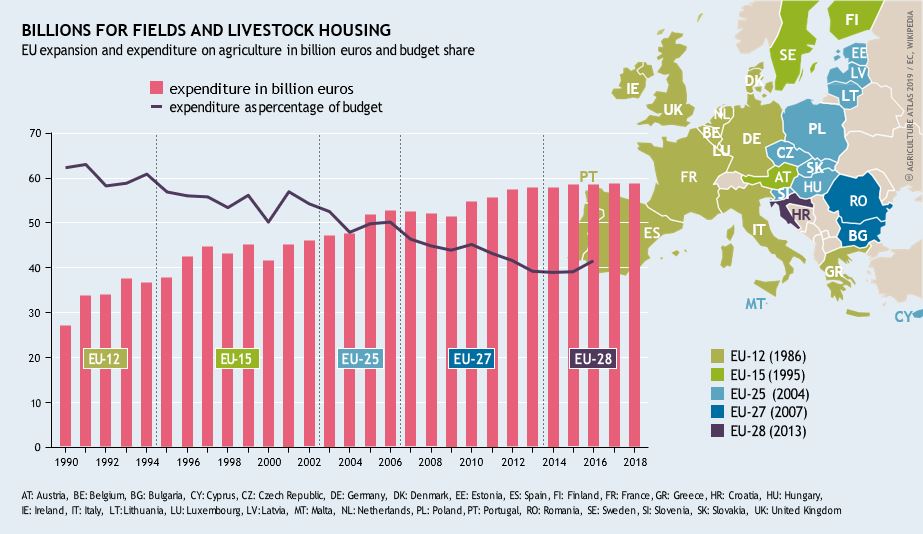

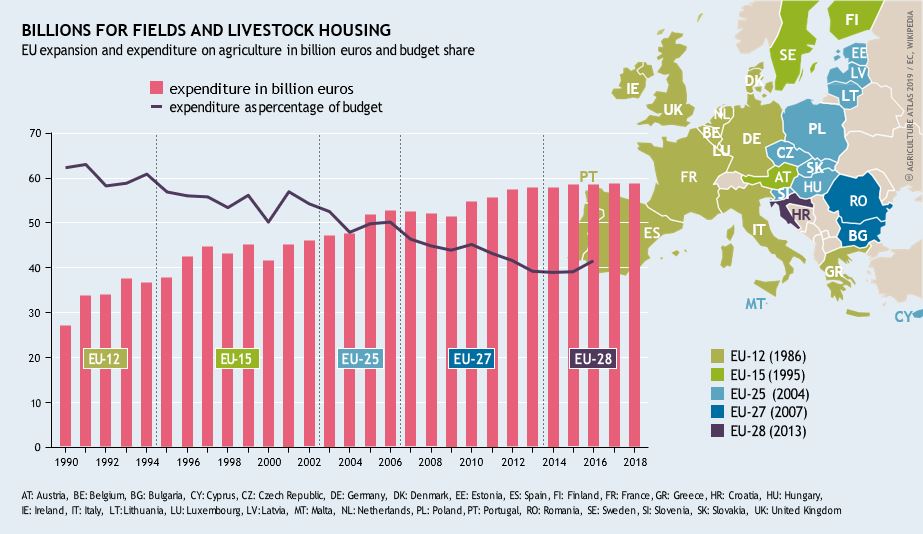

Agriculture is no longer the main theme for European integration, but it still takes the biggest slice of the budget.

Although the Common Agricultural Policy has been reworked many times and the export subsidies have disappeared, a new set of objectives that would address the challenges of the 21st century has never been agreed upon. First and foremost, the massive influence agriculture has over nature and the environment – the quality of soil and water, as well as habitats of insects and rare plants are inseparable from agricultural production. Protecting the environment, animals, the climate and human health and the development of rural areas, as well as the disappearance of small scale farms are major challenges that should be regulated at the European level. Despite this, the Common Agricultural Policy fails to deal with them systematically.

How does a reform of the Common Agricultural Policy come into being, complete with new priorities, payments or spending cuts? First the European Commission comes up with a proposal. This is discussed and amended by the European Parliament and the Agriculture and Fisheries Council (composed of ministers from all 28 EU member states). It is then decided on through laborious discussions, known as a “trilogue”, between these three institutions. Once the law has been agreed, its provisions must be implemented through national laws and rules in each member country. This means all three institutions carry the responsibility for the future policy. Time and again, small-scale farmers’ organizations as well as environment and development groups complain that the negotiation process waters down any attempts to make the Common Agricultural Policy more just or sustainable. For many years, the most important goal of the policy has been to stabilize farm incomes.

Smallholdings dominate in several EU countries. For some families they are the main source of income; for others they are a sideline.

Agriculture currently accounts for 38 percent of the EU’s budget, or around 58 billion euros a year. In other words, every citizen pays 114 euros into the EU’s agriculture fund. Agriculture takes up the biggest chunk of the EU’s budget, though its share is shrinking. In 1988 it was 55 percent; by 2027 it should be only 27 percent.

That budget is divided into two parts, or “pillars”. Pillar I, the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund, accounts for 75 percent of the money. This pot of funding is used to make payments to farmers based on the area they farm: an average of 267 euros per hectare throughout the EU. Because farms vary in size, 82 percent of the total goes to only 20 percent of the recipients. Pillar II, the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development, covers the remaining 25 percent of the funds. It pays for programmes to develop rural areas, organic farming, support for farming in disadvantaged areas, in addition to environmental and nature conservation and climate protection.

Although it is Pillar II that rewards environmental services, the Commission has proposed to cut this budget by 27 percent in the coming funding period. Pillar I would be trimmed by just 10 percent. This is just the latest in a rich history of misguided developments in the Common Agricultural Policy.