When it comes to greenhouse gas emissions reductions, there is a dynamic tension between the ambitious aims of the EU and its member states on the one hand, and the realities of embedded, entrenched elements of the economy such as agri-food on the other. The European Union set target in 2021: a 50% reduction in Greenhouse Gas emissions (GHG) by 2030. Progress remains however, slow. Progress is especially slow in agriculture. Rasmus Larsen unpacks the situation in one of Europe’s intensive agriculture strongholds, Denmark, where, after faltering misfires, a new three way partnership has been proposed. What is this, and will it work?

Agricultural Climate Change Mitigation and Its Discontents

The European Environment Agency (EEA) highlighted this issue in June 2022, stating:

“While emissions have decreased in almost all sectors, particularly in energy supply, industry, and the residential sector, emissions from transport and agriculture have not fallen at a sufficient pace. In fact, emissions from agriculture have increased recently.” (EEA, June 2022)

Another recurring theme in the EU’s climate-related legislature is the 2025 milestone, serving as the first benchmark for evaluating or meeting specific reduction targets. As this deadline approaches, the urgent need for action becomes increasingly apparent.

In response to this urgency, a group of experts, commissioned by the EU, released a report titled “Pricing Agricultural Emissions and Rewarding Climate Action in the Agri-food Value Chain” by Trinomics/IEEP in late autumn last year. (Trinomics/IEEP Report)

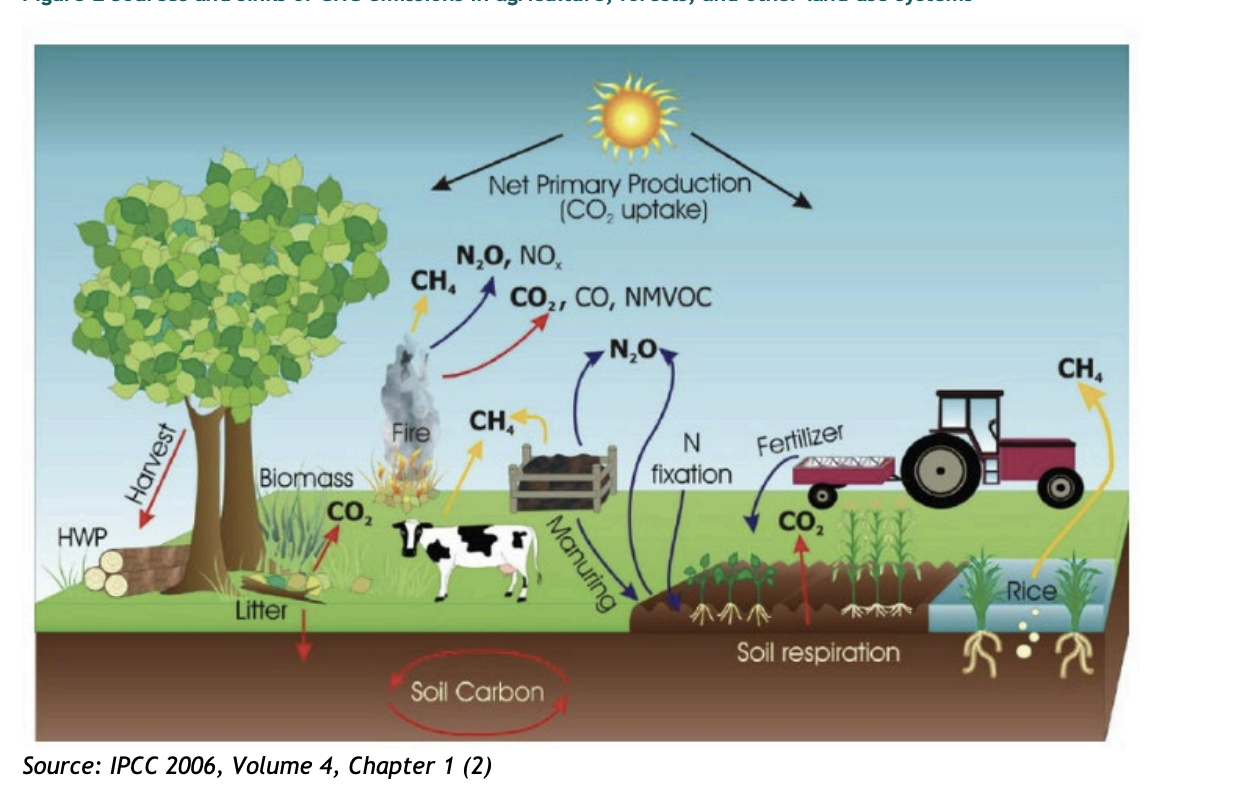

This report reveals that nearly 80% of GHG emissions from European agriculture originate from “Enteric fermentation,” a process occurring in the digestive systems of animals. Specifically, livestock in Europe produce 182.5 million metric tonnes of CO2 equivalents annually.

The report’s first section focuses on identifying ‘the polluter,’ differentiating between ‘upstream’ sources (like fertilizer producers) and ‘downstream’ contributors (such as meat factories, burger bars, and ultimately the consumer). The second part, spanning 322 pages, details various emission and data-collecting points, taxation options, and the efficiency versus administrative burden of emissions trading systems (ETS) quotas. The emphasis on ETS, mirroring the quota system used in European industry, suggests Brussels’ inclination towards this approach.

This report ostensibly lays the groundwork for a legislative proposal for an EU 2040 climate target, amending the European Climate Law. However, with EU elections looming and no common regulation framework for agricultural GHG emissions in sight, the report may serve more as a source of inspiration -or consternation – for member states than as a blueprint for future legislation akin to the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

Despite the various strategies outlined in the report, the inevitable reduction in livestock seems to be a necessary step. This realisation is gradually dawning, however slowly and fractiously, among countries with significant livestock populations, such as Ireland, the Netherlands, and even non-EU member New Zealand. The Netherlands, for example, plans (if that’s not too strong a word) to reduce livestock numbers by purchasing and shutting down farms, a strategy recently approved by the Danish Commissioner on Competition, allowing the use of state finances for this purpose.

Denmark, with its substantial annual livestock population of 25 million pigs and 1.5 million cows, is taking a different approach. The Danish government is considering an indirect method: planning a yet-to-be-defined tax on CO2e emissions at the farm level.

The CO2 Tax on Agricultural Production in Denmark

The introduction of a CO2 tax on agricultural production has been on the cards since the Climate Law of 2019, also known as the 70-30 law. This law, named after its target of a 70% emissions reduction by 2030, was signed by every major party in the Danish Parliament, including those representing farmers. Despite this consensus, concrete actions have been slow. Various expert groups, commissions, and researchers have struggled to devise a taxation model acceptable to the farming community. Meanwhile, the agricultural sector continues to receive substantial funding for research into technological solutions that could reduce emissions without decreasing livestock numbers. These so-called ‘technical abatement measures’ have received significant investment.

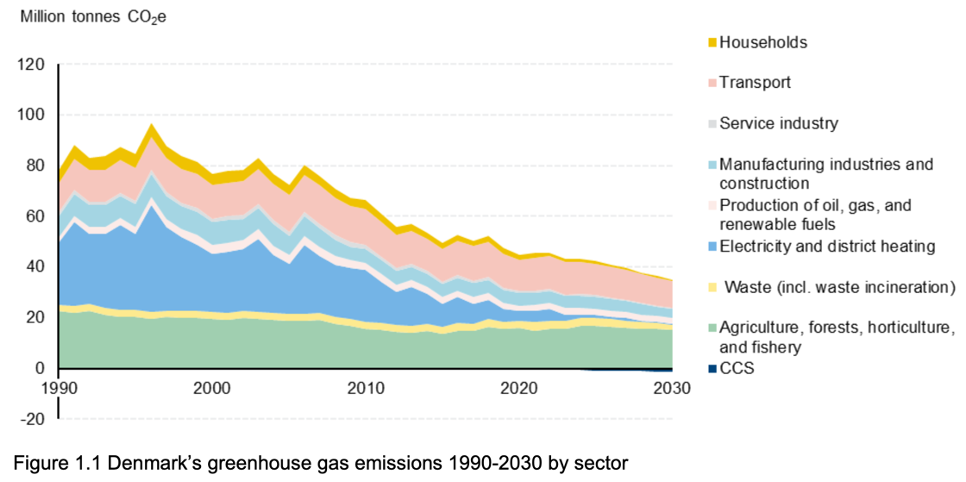

While other sectors have gradually adjusted and decreased their emissions, agriculture’s share of Denmark’s total emissions has conversely increased. This rise has made it increasingly politically unviable to delay action on agricultural emissions.

That was then, this is now

This situation influenced Denmark’s current political coalition. After the last election, the Social Democrats, despite having a center-left majority, chose to form a government with the right-wing farmer’s party (Venstre), likely to avoid political fallout from imposing the CO2 tax on farmers without bipartisan support. The agricultural tax was included in the coalition manifesto. However, despite some MPs from Venstre joining opposition forces to attack the tax, the coalition’s political leaders have affirmed that the tax will target production.

Yet, as often happens with agricultural regulation in Denmark, numbers and facts are disputed by the agri-lobby, leading to political hesitation and the appointment of supposedly independent expert groups to clarify matters. This process typically results in delays and inaction. In this case, two years into the expert group’s tenure, an unexpected amendment to their original mandate was introduced, further complicating matters. The amendment proposed considering a consumer tax model, a concept widely regarded as inefficient by economic experts, as it fails to incentivise farmers to reduce emissions. The frustration of the expert group’s chairman with this amendment was publicly expressed.

In contrast, the Danish Climate Change Council (DCCC) presented a taxation model for farms in February 2023, which garnered support from all stakeholders except farmers. This model, detailed in the DCCC report, suggests a carbon tax of DKK 750 (approximately 100 €) per tonne of CO2e, which could reduce emissions by around 45% compared to 1990 levels when considering existing technical measures alone. However, to achieve the 55-65% reduction target for agriculture and forestry by 2030, a combination of new technologies and changes in production systems is necessary. The DCCC warns that focusing solely on technical measures could slow the green transition, locking the agricultural sector into carbon-intensive practices.

As a result of the amendment, the expert group’s progress was reset. Recently, however, there have been signs of political determination to move forward. The leader of Venstre confirmed the impending tax, only to be replaced shortly after by a new leader nicknamed ‘Tractor-Troels.’ Following this leadership change, the expert group announced their inability to meet the deadline. To those unfamiliar with Danish politics, these developments may seem implausible.

Further complicating matters, a brewing scandal has emerged, involving journalists seeking access to correspondence between the agri-lobby and the expert group. This request was denied, contradicting the norm under Denmark’s public information act, and is currently under investigation by the Danish Ombudsman.

And now? Let’s Try a Three Way Partnership

So where are we? It is hard to say, but the current official prognosis is that the expert group’s report will be made public in early spring. Then the actual law-proposal will be drafted in a ‘three-way-partnership’ – something quite extraordinary – where the agri-lobby, the green NGOs and the ministers for Finance and Economy – chaired by Tractor-Troels – will discuss, agree and formulate the specific wording of the regulation administering the tax. This work is estimated to end in June and – as I understand it according to the homepage of the Ministry of Taxation – with no hearing-phase, be passed in Parliament before the summer holidays.

Looking across the border to Germany and Holland where recent attempts by the governments to mitigate farm-related GHG-emissions or other pollutants have been met with severe disruption an some discontent, there is some logic to the Danish ‘three-way-partnership’ model. Whether it can deliver on the reduction targets within the next twelve months, and beyond, remains to be seen.

Keep Reading…

EU Digital Agriculture Needs Clear Socio-Ecological Directions

Who will Deliver the Science and Research for a Sustainable Food System?

Marburg Gathering | Building Bridges for Future-Proof Food Systems