by Bálint Balázs

by Bálint Balázs

A newly published paper seeks to reposition legumes as protagonists in policy debates and encourage us to identify policies that would better support the transformation of European food- and feed-systems to a new norm, with greatly increased production and consumption of homegrown legumes and homegrown legume-based products. Read on for a savoury account of legume policy by lead author Bálint Balázs.

Legumes are the most versatile, exciting and beneficial ingredients for sustainable and healthy diets – with bonus potential to reduce the impact of agriculture on the environment, including climate change mitigation. Why then is legume consumption and production so low across Europe? How do policies shape or distort the playing field in favour of more homegrown legumes?

Benefits

Legumes can deliver multiple agronomic, environmental, and social (health) benefits, enhancing the sustainability of diverse cropping systems and across Europe’s varied pedoclimates. Grain legumes present an alternative to meat and dairy protein intake. They constitute a vital plant protein source, health-promoting starches, and other essential macro- and micro-nutrients, plus important non-nutritionals. They are, therefore, crucial elements of a balanced diet low in saturated fat and high in fibre.

The variety of well-thought-out plant-based diets present solutions to the globally rising demand for meat, dairy products and their associated negative impacts. Any dietary change supporting greater cultivation of legumes in Europe would change agricultural land use with risks of profitable production and the transfer of increased quantities of legume-protein to human consumption.

This new, homegrown legume supported paradigm demands a radical transformation of cropped systems in Europe, the EU’s relationship with a globalised agri-food system.

Barriers

As the market for plant-based diets is growing rapidly, legume grains (such as peas, beans and soybeans) become the stars of foods associated with improved health and low environmental impacts – in their own right, not as meat substitutes. Yet, the EU is a significant net importer of such grains and largely serves the increased demand for the animal feeds that drive meat and egg production. Consequently, despite the multiple agro-environmental benefits and the rising human-market incentives, legume production and consumption in Europe are still low, and these potential benefits are forfeited.

The new insights of our research approach, which involves working with a wide range of stakeholders and experts from across the value-chain, identified several policies to realise the benefits which only homegrown legumes can provide.

However, the prospects are hindered by five main barriers:

- CAP and trade policies focus on production without sufficient support along the value-chain, without a direct focus on legumes, and thus agroecological services are undervalued by producers and society.

- N fertiliser policies have not appropriately stopped the over- and inefficient use of synthetic nitrogen fertilisers. The risks of N loss by leaching or as greenhouse (i.e. global warming) gases persist.

- R&D policy (especially in breeding and processing technology) is insufficient for both state-financed or private institutions. Innovation programmes are few, and investment opportunities low.

- Policy coordination of knowledge transfer is weak among extension services, processing facilities, and trading companies. This creates difficulties in supply and demand which can be resolved where policies focused upon (for example) decoupling use of imports by the feed sector, ensure label homegrown legumes and legume-derived products, redeveloping regional food culture and creating short regionalised feed- and food chains. Consequently, the profitability of legume production is questioned by farmers (due to pest control, variable yields, competitively priced imports, e.g. soybean – despite the high environmental cost of their production). Such added market risks cannot be obviously offset by the wider environmental (or societal) benefits.

- Finally, consumer-oriented food policy, e.g. including public food procurement and dietary guidelines, do not focus on creating a better public perception of legume grains or legume-based products as food. Good eating initiatives fail to products to good-nutrition and -health, or potential to transform such provisions via convenience- or snack-foods industries, nor is their easy-access and educational frameworks on cooking legumes in easy-to-follow recipes.

Enablers

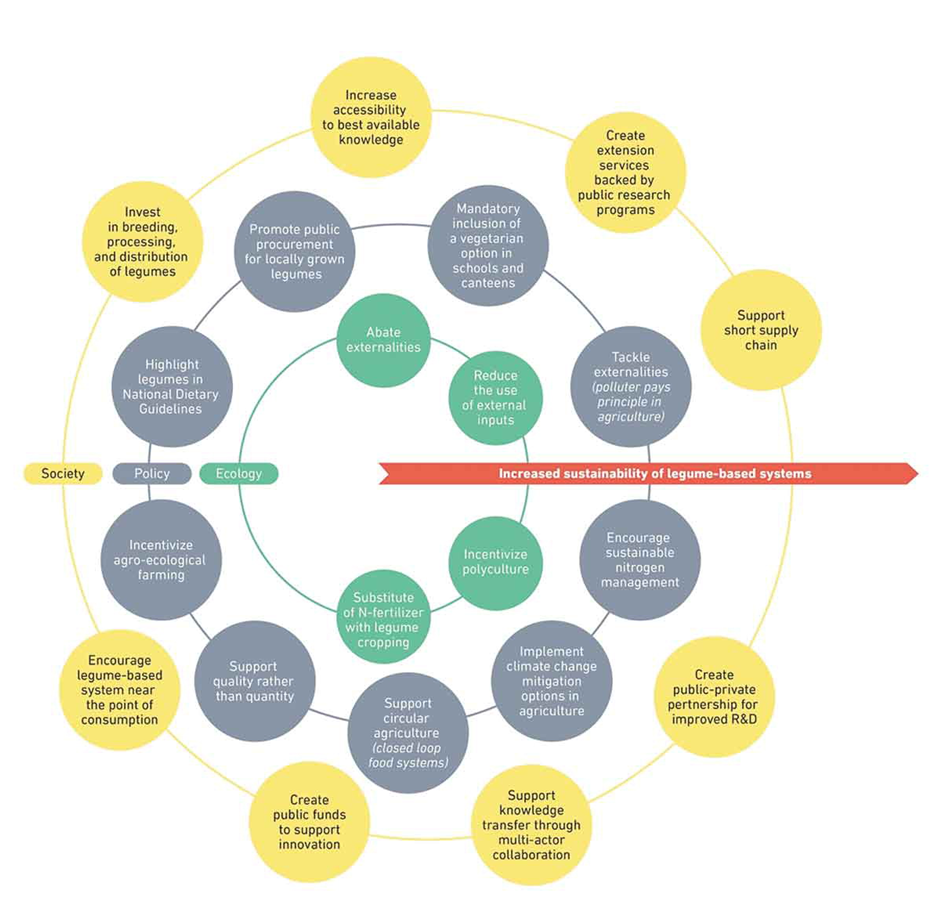

Stakeholders and value chain actors in the TRUE-Project’s Legume Innovation Network easily identify several homegrown legume ‘enablers’, such as proximity to processing facilities and the existence of legume-grain trading companies and access to independent extension services (i.e. agronomic advice to optimise legume production), and regional support and innovation networks and training programs – see the figure below.

Policy case studies were conducted in seven European countries (Croatia, Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Portugal, and Scotland). They focused on different upstream and downstream components of the value chain to explore policy approaches that support legume production and consumption and main policy challenges.

Legume production is supported within ‘Greening Measures’ (crop diversification) and within agri-environment schemes (i.e., Ecological Focus Areas (so-called ‘EFAs’) in the CAP, or Common Agricultural Policy). However, member states choose to apply these measures voluntarily, without having a long-term goal, and so impact on the sustainability of ecosystems or societal attributes remain unchecked. Therefore, and to upscale homegrown legumes more effectively within these Greening Measures, it would be necessary to specify specific crop-plant families such as legumes for preferred management options.

Furthermore, within the EFAs, legumes do not provide the same level of biodiversity provision as accommodated by other EFA options, such as hedgerows, buffer strips, afforested areas, etc., yet may be remunerated as such.

Even so, such promotion of legumes via promotion of great crop diversity (and allied reductions in polluting synthetic N and pesticides use) has still been insufficient to ensure more legumes to farmers’ fields and consumers’ plates.

However, regional policies within the CAP still play a clear role. For example, Germany implemented its Protein Crop Strategy “Diverse crops on Arable Land”, which is part of agro-environmental and climate protection measures under the CAP Pillar II.

The Farm Advisory Service in Croatia has also implemented the “Strategic Plan of Work for Period 2018–2020 N.14 professional supervision of integrated farming”, which encourages legume production at the level of national legislation. Legume-supported value (or supply) chains require such integrated policies that enable infrastructure and market development.

In Germany, tofu companies have recruited farmers with steady demand and product valorisation from non-GMO soybean cultivation and advice from extension services and knowledge transfer.

In Italy, the demand for non-GMO soybean by the dairy industry (Consortium of Parmigiano Reggiano) provides significant and consistent demand for homegrown legume grains – the processor ensuring smooth operation of the value chain from the production side and seed procurement (contract growing) to harvest. This is achieved via dedicated extension services and the availability of improved varieties that can better withstand climate change (increased weather stochasticity) and pest attacks.

On the consumption end of the value chain, the impact of homegrown legumes is still small-scale. Yet, the Organic Eating Label in Denmark increased organic legumes both for food and feed.

Public procurement schemes in Denmark, Portugal and Hungary also created more room for healthy foods, vegetarian options, and the potential to increase legume consumption in public canteens.

In Scotland, private sector-led initiatives started using legumes in animal feed, especially aquaculture; developed new products based on homegrown grain legumes; introduced new legume varieties and innovative practices; plus, promoted public health and dietary change.

Pathways

The policy analysis and in-depth case studies at the EU and national level identified three major pathways for increased sustainable legume-based systems:

1. Capitalise on ‘ecological enablers’ to improve homegrown legume-based agri-food systems

Policies that support the reduction of mineral (synthetic) N fertiliser can indirectly incentivise legumes, and properly managed legumes will help maintain soil and water qualities and reduce GHG emissions.

For example, the EU Nitrates Directive (91/676/EEC), which is closely aligned with the EU Water Framework Directive (2000, 60/EC), limits the amount of nitrates from agricultural sources to protect water quality by limiting practices such as crop fertiliser rates, animal-stocking rates, and animal access to waterways. However, these directives are implemented differentially nationally and even regionally, and iterations could recommend substituting highly N-fertilized crops with legumes (grain or forage types).

However, any increase in the cost of carbon emissions by taxing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions at a relatively high rate would make N fertiliser more expensive and thus legumes more attractive. An inspiring example is the nitrogen emission ‘permit system’ introduced in 2015 in The Netherlands. Feed self-sufficiency is prioritised by grazing locally cultivated legume grains and/or legume-grass swards. If adopted, this approach would nurture 50% fewer animals.

2. Create a supportive and coherent policy environment

Policies that support legume-based cropping systems near the point of consumption would be needed, incentivising local producers and processors to include legume in their cropping systems. Products from eco-agri-food systems command a price premium which is most commonly afforded only by the more affluent consumers. Farmers’ support linked to quality, environmental protection, and varied crops with high nutritional value should be incentivised.

As exemplary policies for more sustainable food production France introduced a law in 2014 (LOI No. 2014–1170 d’avenir pour l’agriculture, l’alimentation et la forêt) economic, environmental and social benefits via agroecological practices.

The German BÖLN Scheme funded by the Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture supports directly through the CAP organic farming measure within the Rural Development Programmes.

On the consumer end, policies increasing the demand beyond the price support are needed for a higher uptake of legume-based foods via targeted campaigns and marketing of legumes’ health- and environmental-benefits. Consumers’ “food literacy” is a prerequisite to any dietary guidelines.

Inspiring examples of such educational campaigns come from Portugal, which places legumes in a dedicated section of the food wheel guide, from The French National Nutrition and Health Program’s dietary guidelines (Guides nutritions du Programme national nutrition santé (PNNS)), that highlight three categories of action one of them being the increase of legume consumption, and the Canadian Food Guide 2019 that emphasises plant-based protein foods within the “protein foods” group by placing beans and lentils at the top of the list before nuts, other seeds and animal protein products (meat, poultry, fish, eggs and dairy foods).

3. Engage actors along the value chain and from the broader society

We traced a significant gap of importance and influence between value-chain actors.

On the consumption policy side (e.g. procurement and nutrition-oriented policies), regulating bodies, consumer groups (e.g. parents association in Portugal), professional organisations (e.g. association of dietetics in Hungary) and processors (i.e. catering companies) seem to be the most influential actors.

In the middle, we found farmers and actors at the lower end of the value-chain appear to or are treated as if they have much less influence.

However, actors at the production endpoint of the value-chain (e.g. seed suppliers, crop breeders, agronomists) tend to have an equally important role as actors at the consumption endpoint, as they can have a significant impact on how the increased demand for raw materials or commodities can be met.

Case studies analysing policies that focus more on the production (and processing) segments of the value-chain indicate that processors and agronomists are equally important and influential players as farmers themselves and state regulators. At the same time, crop breeders, seed suppliers, or civil society play less relevant roles.

However, in situations where existing and widely used breeds are not profitable enough, crop breeders and seed suppliers would be key actors, and support for research and innovation could contribute strongly to an increased volume of legume production. In some cases, multi-actor networks including farmers, advisors and breeders fill such gaps (e.g. in Germany), while in other situations, one or a few market actors fill this niche and provide novel breeds and technical knowledge to farmers (e.g. in Italy).

These requirements press for a coherent single agri-food policy, bringing together fragmented and inconsistent policy components to create simultaneous incentives for value-chain actors.

Read the full paper here.

Balazs, B., Kelemen, E., Centofanti, T., Vasconcelos, M. W., & Iannetta, P. P. (2021). Integrated policy analysis to identify transformation paths to more-sustainable legume-based food and feed value-chains in Europe. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 1-23.