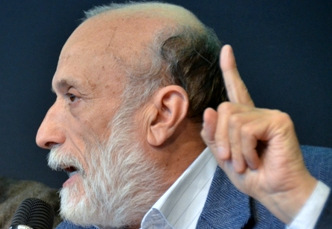

It may be too late to completely change the big pictures of Europe’s agricultural policy overnight, but Slow Food founder Carlo Petrini argues there are two simple and concrete measures that could still have a major impact on the sustainability of the CAP reform. Below you can read our translation of an original article from La Repubblica.

Ideas for an Eco-Agriculture

While Italy is stuck in a vacuum of government that is difficult to solve; people with real needs continue to knock on the doors of politics. Every day this knocking is becoming louder; the objectives clearer. Just last week over 270 non-governmental organisations clearly and loudly presented yet another key issue to the European government: We are no longer willing to accept that public money from the Common Agricultural Policy (the famous CAP) is used to support agricultural practices which ignore the value of public goods, the environment, and the protection of non-renewable resources such as groundwater and soil fertility.

It is no longer acceptable that the money of European citizens is used to support this form of agricultural production. It is simply immoral to collect money that pollutes and impoverishes Mother Earth, and ignores what consumers and many citizens – the people paying the taxes – are saying. We will no longer accept a CAP that provides a choice regarding whether or not to adopt environmentally-friendly practices: Sustainability cannot be optional.

The signatories of the letter have shown, with quiet confidence, that they are able to separate the wheat from the chaff when it comes to food security: the production of food for a continent with half a billion people is not a problem to be addressed lightly. However agriculture can no longer live oblivious to the fact that direct payments (the bulk of the farm subsidies, to date all determined by the size of a farm) influence the environment, landscapes and global markets, plagued by competition for food that, if there were no money in Brussels, would not be produced or could not be sold around the globe. Besides the damage, they also make a mockery of developing countries that have to compete with those whose production costs are financed by the institutions.

The new CAP cannot simply reduce subsidies. It must be connected in an inseparable way to the adoption of environmentally-sustainable practices. The path must be progressive, but at certain stages, and if necessary, enforced: A little ‘make-up’ would not fit these hundreds of associations. And if you should think someone can make sense of these thousands of streams of fragmentation, well you are wrong. This is a virtuoso, a colossal example of unity in diversity, for the affirmation of the absolute value we place on the earth on which we walk. A ‘little’ green washing as they call it in English is not going to solve this: just like pneumonia does not simply require an aspirin. For this reason, aid for rural development should always be preferred to direct aid as it has positive elements for example helping young people to start a farm, helping farmers better meet the criteria of sustainability or encouraging the choice to farm organically. While we obviously cannot simply drain all the funding “per hectare” out of the blue, there are at least two good measures that can be taken in the first pillar now.

The first measure is crop rotation.

A simple and efficient way to maintain soil fertility is to cultivate different plant species on the same ground, alternating from year to year. It reduces diseases (which require chemicals to be treated or prevented) and the requirements of certain nutrients (the same plants always require the same elements and thus intensive fertilisation), but above all it increases yield and environmental quality. It is like the egg of Columbus, but to the intensive agro-industry, with companies sowing the same things on the same soil, year after year, crop rotation seems like the plague: Diversity, we are told, is not the winning business model – as if the earth was just a great assembly line.

In order to appease us, the drafters of the CAP considered “diversification” as equally green. Diversification is not the good rotation, but rather the cultivation of different crops alongside each other; the same plants on the same plot, year after year. That is not how it works.

The second proposal concerns the amount of subsidies. Not all hectares are equal! Small-scale agriculture is more sustainable and more responsive to the needs of the territory, often carried out in marginal and geologically-fragile areas, where it is more important to preserve values that go beyond the price of commodities. Ever since the Roman Gracchi brothers Tiberius and Gaius first suggested it, small-scale agriculture has been seen as vital to the health of a developed society. Meanwhile, large estates result in the degeneration of our relationship with Mother Earth as she becomes a commodity. Today we talk about capping: No farmer needs more than 300 thousand euros of subsidies, even when the number of hectares would entitle them to more. But that is not enough. We ask that the direct aid is paid “to scale”: 100% of the amount should be paid only for the first 5 or 10 hectares and then be progressively decreased to 0%. Of course this is just an example and different sizes could be determined for different forms of production and in different countries. But the principle is clear: We trust a multitude of small farmers more than a handful of landowners.

These two simple ideas we share with those who care about the future of agriculture in the old continent Europe, such as the associations gathered in ARC2020. We don’t ask for much. We simply propose concrete measures to ensure that only an agriculture that appeals to and serves everyone’s lives will receive our money. In these times this appears to be a revolutionary necessity!

Carlo Petrini