While the next CAP reform is still in discussion at the Council, and the European Parliament has not yet taken a final position, Samuel Féret explains the rationale of the new concept of CAP Strategic Plans (CSP) for a future CAP as proposed by the European Commission. This is intended as a pivotal piece of the future new delivery model, probably the biggest proposed change in how the CAP is set to operate in the future. The first in a five part article series on where next for CAP.

In the first part below, Féret explains what the opportunities and weaknesses of the strategic plans regulation (SPR) are, starting with an appraisal and moving into a critical assessment. Upcoming articles in the series will focus on the previous report voted in the European Parliament’s Agriculture Committee (Comagri) as well as on ongoing talks at the Council, and on how the relationship between the two institutions may play out. Following this, Féret will take some lessons from the previous CAP implementation in 2015 – what are the factors that influence member state, national level choices? The final section will conclude with some guidelines for how to prepare their CSP. This will be of use for non-sectoral stakeholders when influencing and participating in their design at national level, while also adding to the discussion on a possible logical framework-oriented matrix for a CSP at European level.

Part 1: CAP | What is the Proposed New Delivery Model?

Part 2: CAP | What can we Expect from the Strategic Plan Regulation?

Part 3: CAP | What influences CAP Implementation Choices?

Part 4: CAP | How to prepare Strategic Plan Regulations – a stakeholder guidance

Part 5: CAP | A matrix’ proposal for designing CAP Strategic Plans

Part 1: CAP | What is the Proposed New Delivery Model?

DIY – do it yourself. This is the core of the paradigm shift in how the European Commission wants CAP to functioning from now on. The Commission wants the Member States to take on more responsibility in planning CAP investments and policies, and to do so from the beginning. This reform germinates a real paradigm shift. From now on, the European Commission delegates the conception of the CAP to the Member States. Since Member states will be directly responsible for CAP – its design, implementation and evaluation. Furthermore, they will have to report on the results of their strategic plan and its impact with regard to the objectives and needs identified. Brussels will no longer be held responsible for the errors of the CAP – at least that’s the theory.

At first glance, the European Commission appears to be giving more strategic power to member states and to follow the subsidiary principle. It appears to have taken on board recommendations from the European Court of Auditors, which had criticised the lack of efficiency of the CAP. Also The member states – the first users of the CAP -– had asked for a more flexible CAP. The Commission appears to have also taken into account external reports conducted on its behalf – the mapping and analysis of the last CAP reform, which had pointed to the lack of strategy and an ever more complex policy.

There is concern too that the EU and its member states are getting value for money from the first communautarized EU policy in expenditures terms (€60 billion for both pillars in 2007), which in turn relates to the legitimacy of attempting to make policy on this scale. Furthermore, the 2013 CAP reform, when implemented, did not simplify the CAP in practical terms for users – both for farmers and national administrations.

The CAP is again expected to provide answers to a number of challenges that are becoming even more intense. Climate change and the collapse of biodiversity are increasingly at the forefront of the meta-issues, whose accumulated evidences form fertile sediment conducive to public action. It is undeniable that food security relates to the health of nature – or, more technically, to In fact, ultimately, our food security depends very much on the good state of natural capital to provide the ecosystem services needed for the production of agricultural commodities. These include (pollination of plants, carbon and nitrogen cycles, air and water filtration, and many more etc.).

The agricultural sector is also looking for answers that can protect farmers’ interests in the food chain, against both climatic and market hazards. Even if not so named, rural renaissance is another crucial meta-goal in terms of job creation, local development and the renewal of generations of farmers – CAP after all has rural policy in its remit. Somewhere in the face of agricultural demographic erosion, agriculture will have no future without the entry of new farmers and new first time entrants.

Finally, society as a whole is calling on the agricultural sector to improve practices in a number of the areas – of health, animal welfare and the reduction of food waste and agricultural losses.

A Performance-Driven Framework

To address Member States concerns about the administrative burden of the current CAP and ECA’ concerns about the lack of results, the EC proposed a “New Delivery Model” that would shift from compliance towards performance. This new methodology is supposed to brings simplification and towards a modernised CAP: as the strategic plan would cover the three aspects of the CAP: direct payments, common market organisation and rural development.

Implementation modalities are at the core of this new methodology, whether it’s viewed from the institutions to the member states or vice versa. There is a logical overarching framework to guide member states – there are nine key objectives (see next section), a range of instruments and member state respective needs. From the member state’s perspective, the pathway is needs to instruments to objectives. This new methodology puts implementation modalities at the core while a logical framework should guide Member States, from their respective needs to instruments for each specific common objective.

However, the EC has pre-empted common needs for all Member States: to raise the environmental and climate ambition and to boost generational renewal. Furthermore, Commissioner Hogan has also added that each CSP should include a strategy to promote bio-economy.

SPR describes a performance-driven framework with architecture based on evaluation criteria and monitoring. The EC will set common indicators (context, outputs, results) and member states will have to define their own targets to be achieved. This will serve a matrix for monitoring and evaluation before prior to a yearly performance review.

A reward and penalty system is foreseen depending on the performance level. When one or more result indicators deviates by more than 25 % from the ad-hoc milestone or initial target, the EC can ask the member state to provide corrective actions. A 5% performance reserve would be set aside and released once result indicators have achieved at least 90 % of their target by 2025. However, it’s still unclear how far impact indicators will be used in such process. It’s worth remembering that other EU programmes like ERDF (European Regional Development Fund), already applies a performance framework –and is results-based – for paying or de-committing money to beneficiaries, depending in what extent milestones and results are achieved.

Nine Objectives for the next CAP and their Qualification

The SPR details nine specific objectives as listed in the table below. It’s a valuable contribution to put specific objectives in the main basic act. Currently, general objectives of the CAP are set in the Treaty on Functioning the EU (TFEU) while some are specified in the horizontal regulation for monitoring and evaluation of the CAP’ performance.

These include: a) viable food production, with a focus on agricultural income, agricultural productivity and price stability; b) sustainable management of natural resources and climate action, with a focus on greenhouse gas emissions, biodiversity, soil and water; c) balanced territorial development, with a focus on rural employment, growth and poverty in rural areas (article 110 of the horizontal regulation).

The nine specific objectives of the CAP beyond 2020

(a) support viable farm income and resilience across the Union to enhance food security;

(b) enhance market orientation and increase competitiveness, including greater focus on research, technology and digitalisation;

(c) improve the farmers’ position in the value chain;

(d) contribute to climate change mitigation and adaptation, as well as sustainable energy;

(e) foster sustainable development and efficient management of natural resources such as water, soil and air;

(f) contribute to the protection of biodiversity, enhance ecosystem services and preserve habitats and landscapes;

(g) attract young farmers and facilitate business development in rural areas;

(h) promote employment, growth, social inclusion and local development in rural areas, including bio-economy and sustainable forestry;

(i) improve the response of EU agriculture to societal demands on food and health, including safe, nutritious and sustainable food, food waste, as well as animal welfare.

The nine specific objectives proposed in the SPR are clustered into three categories: a) incomes, market and value chain; b) climate, natural resources, biodiversity and c) generational renewal, employment and societal demands.

The numbering of CAP specific objectives follows a logical pathway that set priorities, from farm to fork, from farmers needs to societal demands. While some specific objectives already exist, some have been reframed, their scope enlarged or are branded new.

Obviously, objective a) relating to farmers’ income and food security is the number one according to the TFEU goals and objectives. Objective’s b) and c) serve the economic dimension of the CAP. Specific objective b) mentions research, technology and the now fashionable digitalization, but omits curiously innovation that is yet a core element of the CAP through the EIP-Agri.

Objectives d), e) and f) serve the contribution of the CAP to the EU environmental strategy and climate commitments. Objective g) on attracting young farmers is very welcome though it does focus on “young” only. Renewing the farming generations without considering more broadly new entrants (i.e. those who are above 40 years old) could be difficult. In addition, unlocking access to land is not addressed under this line while this is the main obstacle preventing future farmers.

The final specific objective i) gathers various societal demands on food, healthy, safe, nutritious and sustainable food, food waste and animal welfare -it seems like a last minute shopping list to address for the concerns of the EU citizens. This objective is not very specific as it embraces various aspects that do not necessarily relate to each other. One wonders how far results could be reviewed properly since proposed indicators to measure “at the same time” objectives could cause headaches to evaluators as appropriate criteria do not exist at the moment.

Wanted: New Instruments for Specific Objectives

What’s strikes the attentive reader when looking at the proposed SPR, is the chasm between these expanded objectives and the tools – or instruments – to address them. Concurrently, there is a downward trend in CAP expenditures which is likely to hit the whole architecture hard.

And yet, despite everything, its “plus ça change plus c’est la même chose”. Indeed, hectare-based payments remain the main intervention type to address almost all objectives (basic support to sustainability, eco-scheme, coupled payments, agri-environmental and climate schemes, payments for areas under natural constraints, top-up for young farmers, sectoral aids…). Thus interventions modalities are set to remain more or less the same as today. After the Omnibus regulation adopted in 2017, there’s no major improvement in the Common Market Organization regulation.

There’s nothing new here either regarding the interventions to address climate and environmental challenges, though a so-called eco-scheme is replacing the greening package. The number of measures under Pillar 2 is streamlined and collective and territorial approaches to agri-environment are underestimated while the SPR offers a privileged space for bioeconomy.

The current CAP did not deliver enough to cut greenhouse gas emissions since 2012 through its hectare-based lens. So, why does the CAP still release mainly ha-based subsidies? The CAP could have try out other financial instruments to support ecological and climate transition. Yet it has failed to incorporate innovative financial instruments such as “green” loans or premia and other mechanisms borrowed from innovation funding, the kind many start-ups and SMEs engaged in ecologic transition utilize. Is the CAP still the right instrumental framework to support the transition to a carbon-free economy, agroecology and innovation? CSPs will bring the answer.

For many Member States, adopting a strategic plan can be seen as an opportunity to rationalize a policy whose effects are contradictory and whose logic does not always make sense. This lack of coherence is particularly stark in the contrast between pillar 1 (direct payments) and pillar 2 (rural development policy). While certain pillar 2 measures encourage a change of practices (agri-environmental and climatic measures), this contrasts with pillar 1 basic payments which support the status quo (though convergence and redistributive payment have very slowly mitigated this tendency.).

Achieving More Objectives with Fewer Resources

Analysis of SPR cannot be isolated from the Multi-Financial Framework (MFF) proposal for next programming period (2021-2027 or 2022-2028?) which includes CAP expenditures. The latter (EAGF and EAFRD) are still categorized under a natural resources-oriented heading.

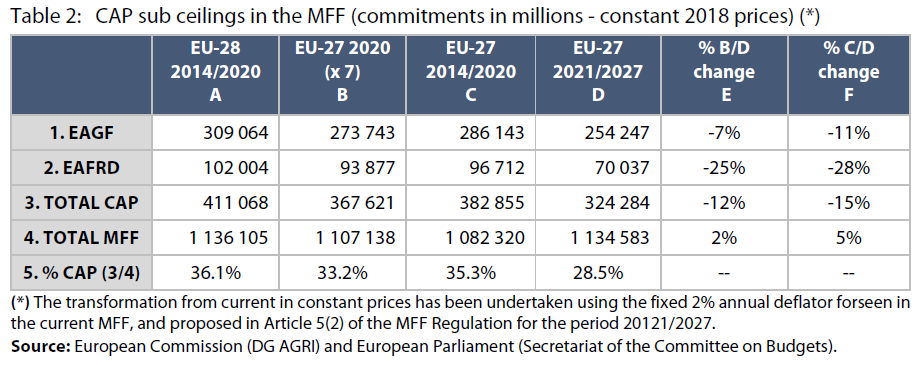

When releasing the MFF proposal in May last year the EC pointed to a 12 % decrease in current prices for CAP expenditure. Analysts answered this would mean a 15 % cut in constant prices and even a 28 % cut for Pillar 2 as shown in the table below, column E [9] and see here on Alan Matthews blog). Furthermore, the Member States could be asked to rise their national co-funding under the EC’ scenario.

So what was the signal sent by the EC to Member States? With a likely more indigent Pillar 2 in the next period, the CAP could rely more on Pillar 1 instruments to address the nine objectives, while such annual payments would take place within a multi-annual CSP.

Towards a Strategic CAP?

What’s surprising is the fact that the SPR does not foresee any consolidated EU CAP strategic plan that could be more ambitious than the sum of 28 CSPs. Only national CSPs are foreseen to match up with national envelopes of CAP expenditures accordingly. However, one might be surprised by such absence that could be interpreted as a loophole. Indeed, the SPR refers abundantly to the Paris Agreement on Climate and to the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations to be achieved in 2030. Both international commitments have been signed by both the EU and the not only by member states. So, is the delegation of the implementation of both commitments to member states the right strategy to achieve results? Where is the EU-level strategic thinking?

And what about biodiversity? The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) which is supported by the EU, released impressive evidenced-based documentation on species extinction. Agriculture suffers -and will continue to suffer- from the collapse of biodiversity; however its intensive use of chemical inputs and natural habitats’ disturbance (caused by land-use change) is also responsible for such dramatic negative changes. Biodiversity is an overarching objective, so there is a strong case for a pan European dimension to biodiversity protection, as part of a consolidated EU CAP strategic plan.

Last but not least, it’s worth noting the future CAP strategic plans would have to include various sub-strategies to address the wide range of challenges. Whether various farmers unions and other stakeholders back the fashionable bio-economy and digitalisation, fewer have noticed the expected attempts to structure national strategic plans around a knowledge-based agriculture. Each national plan would require an overarching take on agriculture, knowledge and innovation system (AKIS) and on modernised farm advisory services (FAS). Obviously, AKIS and FAS are keys for delivering outcomes and reaching targets. At a time when subsidies are expected to become much less for every single farmer supported by the CAP beyond 2020, farmers will have no choice but to innovate through collaborative and interactive innovation schemes under rural development pillar.

In conclusion, the main signal from the SPR is that Member States will have to implement the budget shortage and to do so only with the blunt tools of today. Can strategic plans help to improve the delivery of CAP promises without genuine new instruments and enough resources? The compass of this New Delivery Model is bounded by four landmarks for the next CAP: strategic, result-based, flexible and simplified. A result-based CAP is the proposed strategy. However, flexibility can hamper simplification of the CAP – as the former means more nuance, subsidiarity, exceptions and options, while the latter means one set of straightforward rules for all. How can all four be achieved at one and the same time?

To follow next: part 2 what can come out of the SPR’ negotiations?

2 Trackbacks / Pingbacks

Comments are closed.