Sebastian Lakner assesses the current, rapidly changing situation of agri-food trade and policies. How is the war impacting on agri-food supplies, and what are the responses at EU and national level? This opinion piece is an English language update of an earlier German post on the agricultural economist’s blog.

The war in Ukraine is a humanitarian catastrophe, but it will also have severe consequences for the agricultural sector in Ukraine, the agricultural world market and for global food security in developing countries. On March 3, 2022 there was a public panel describing the impact of the war on Ukrainian agriculture (see the video in German here), which could be seen as a starting-point of the analysis. In the following text, I outline possible consequences for Ukrainian agriculture and international markets and discuss a number of policy options to react to a potential food-crisis in mid 2022. It must be stated that at this stage many effects are still speculative, as it is unclear how long the war in Ukraine will last and how severe the consequences for Ukrainian agriculture and infrastructure will be.

How does the war affect agriculture in Ukraine?

Currently, it is difficult to get an estimate how severe the destruction will be on the farms. Field work cannot be carried out in the current war-situation. Fuel has been either given to the Ukrainian armed forces or burned. Fertilizers are lacking and plant protection measures cannot be done. Although the winter crops are already in the ground, they cannot be treated further, and the spring seeding (e.g. Maize, summer grains) from March to May is not foreseeable at the moment. The situation of livestock farms is similarly difficult, as animals cannot be fed in some cases.

In addition, the situation of the infrastructure is a disaster, as many roads and bridges have been destroyed by air raids. Exports to the world market take place via the Black Sea ports of Odessa and Mykolaiv, which are in Ukrainian hands, however blocked by the Russian navy. The war is having a disastrous effect on Ukraine, which has (also supported by credits of the WorldBank) invested heavily in its own infrastructure over the past 20 years. Farms have greatly increased their productivity, and transportation has also been improved. In this respect, this war and its destruction will set Ukraine back, although much depends on how long the fighting lasts.

How does the war affect international agricultural markets?

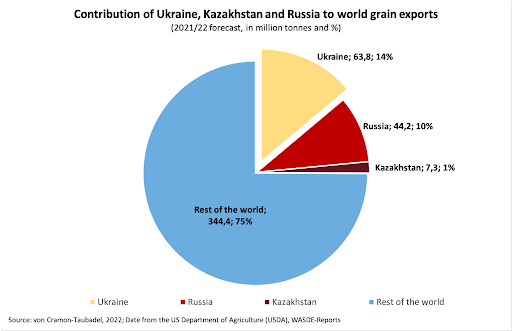

Over the past 15 years, Ukraine has become a reliable supplier of a number of important agricultural commodities. Along with Kazakhstan and Russia, Ukraine has black “Chernozem” soils on which high yields can be achieved. The limiting factor is rather the low rainfall compared to Central Europe. On the grain market, the three countries Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Russia supply about a quarter of the supply on the world market (see Figure 1, see also von Cramon-Taubadel 2022):

It is to be expected that Ukraine will cease to be a supplier of agricultural goods at the world market-level. This mainly concerns wheat, barley, rapeseed, corn and sunflower. In the case of cereals, Ukraine has a share of 14% of the volume traded on the world market in 2021/22. It is difficult to estimate a possible price increase, it depends on the duration of the war. At the moment wheat is already traded for more than 400 EUR/t, usual prices are around 200 EUR/t, already last year prices had increased slightly, to 250 EUR; So the described supply problems meet an already slightly strained market situation.

The role of Russia is unclear at the moment. It is currently not assessable to what extent Russia can export its agricultural goods, because there are sanctions and the Black Sea is blocked by Turkey. However, SWIFT currently excludes medical and agricultural goods. Furthermore, there are countries that have not joined the sanctions. Russia can continue to export via the land route or the Caspian Sea, so that the quantities are at least partially available to the world market. The export routes are only more complicated and the transport of these goods becomes more expensive.

Which countries are affected?

The loss of exports is likely to affect developing countries in particular. Although Ukraine also supplies the EU to some extent, it mainly supplies import-dependent countries in the Middle East (e.g. Syria or Lebanon), the Maghreb states or states in East Africa and Asia. Here we will already lack significant quantities for the supply of this region in the next months.

This point was made in an interesting blog post by Oleg Nivievskyi of the Kiev School of Economics, which shows in great detail that there is a longer list of developing countries (Egypt, Yemen, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Lebanon, Pakistan and Iraq) that are extremely import-dependent and where a high percentage of the population lives below the poverty risk threshold.

The European Union is probably more affected in specific sub-areas, but by no means in a supply crisis. The EU has a self-sufficiency level of over 100% in many areas, so we are net exporters of some agricultural commodities. In 2020, the self-sufficiency was 130% for pork, 109% for beef and 106% for poultry meat . In cereals, we are also slightly above 100% in Germany with slight fluctuations, only in the drought summer of 2018 we were once at 91% (all data: See BMEL 2021: Stat. Jahrbuch Landwirtschaft, p.146 and 299). However, the largest part of the meat production still goes into the EU-market, so domestic consumption patterns with a high demand for meat are a cause of this development.

(*Remark: On Twitter, it has been pointed out several times that the pig parts (e.g. offal, feet) that are exported are not consumed here in the EU. This does not change the basic finding that we have a high consumption of animal feed in Germany and in the EU).

In principle, the EU can somewhat compensate for the outlined problems in procurement through its higher purchasing power. This means that although there may always be supply problems in individual cases. One example is salad-oil from rapeseed or sunflower, where the import-share of Ukraine to the EU is around 80%. Another example is GMO-free soy from Ukraine for the organic sector. However, in total the supply situation in the EU as a whole is not at risk.

How hard is the EU hit and what are the possible responses at national level?

Higher food prices are to be expected and these are unfortunately accompanied by higher energy prices. There are social policies for people with low incomes in many states in the EU. However, this is a policy area that falls under the national competence of the member states. People with low incomes in particular suffer with various issues at the same time, because high heating costs and high gasoline prices are a major problem. Higher food prices are added to this. These individual price increases affect low-income households all at once. It does not seem to make much sense to distinguish between the separate price increases when responding to this situation, because the instruments for social compensation have to look at all price increases simultaneously.

There are various instruments in Germany to alleviate the economic pressure caused by the Ukraine war and the sanctions against Russia for people with low incomes. It is conceivable to adjust the rates for social welfare upward. E.g. in Germany, there is specific support for heating-cost for low income households, the federal government of Germany has already announced to use these options. Another example from Germany is the specific commuter-allowance in the tax declaration. An increase could also provide some cushioning for people with longer commutes to work. (Note however, that this instrument has ecological drawbacks, so in the long run, other instruments should be put in place) Part of the price of gasoline consists of the mineral oil tax, which is the case in many EU-countries; The governments could consider to reduce this tax temporarily, in some member states, this is already implemented.

The German government has already announced that it will look into such solutions, I would assume that this will also be done in other EU member states. In this respect, high prices are a problem for many households with low incomes, but this can be tackled with our social security policies. In the medium term, this is more likely to result in the government having to take on large debts in 2022 and 2023, which will have to be reduced again over a longer period of time. This is not a pleasant situation given the other pressures for reform; Especially in Germany, many ecological or social reforms have been postponed or not at all been considered in the 2010s (e.g. reforming our climate policy, agricultural policy-reforms, reforms in our health-care sector, but also a reform of our transportation infrastructure and our railway-systems), so the budgetary situation might limit the scope for further reforms in the next years, which is another severe consequence of this war, moving the focus to expenditure for military and energy independence.

What are Germany’s and the international community’s options for action?

There are different reactions to the foreseeable supply crisis, but they all come with costs and undesirable side effects; some of these options are not without regulatory problems.

It is important to note that the supply situation on the world market is temporary for now, as it is unclear how long the war will last and how severe the consequences for Ukrainian agriculture and infrastructure will be.

- Focus the debate on what works: The overall message for the agricultural community is: Let us focus the debate on measures, which work in the short run, which have a substantial effect returning amounts of grains to the developing countries in 2022, where the state has regulatory power in the short run and where effects are not offset by market effects. It doesn’t make sense to propose very general agricultural-food-strategies like e.g. changing our diets to zero-meat-diets, this is (if desired at all…) a long-term-transformation of ca. 20 years with insecure outcomes. It is important to discuss these strategies, however, not in the context of the looming food-crisis 2022 and the war in Ukraine. We need short-term measures, which work.

- Act in coordination: Any crisis response should initially aim at short-term effects and be coordinated internationally (i.e. at least at the EU level or via the G7) as far as possible.

- Keep markets open: It is essential to keep international markets open and not to introduce export restrictions which, while easing the supply situation and lowering prices on the domestic market, further aggravate the situation on world agricultural markets.

- Abolish the use of biofuels: Considerable quantities of grain and corn could be released for the world market if the blending of biofuels with mineral fuels is lifted in the short term. Globally, we use 9% of crop production for bioethanol and 5% for biodiesel, according to the 2020 UFOP report (UFOP 2019/20). Biofuel blending is now no longer a technology of the future and could be ended in the short term through legislation. (The factories producing bioethanol would have to be compensated.) This measure could even have a significant positive effect if it were implemented in a coordinated manner internationally, especially with the USA.

- Ask consumers to consume less meat: At the moment we use a large part of the grain production for animal feed in order to export cheap meat. It is to be expected that meat will become more expensive due to the increased cost of feed. The question is to what extent we in the rich industrialized countries want to maintain our meat consumption at the level while grain is lacking as food on the world market. However, it is difficult at the moment to intervene here in a politically regulatory way. Meat consumption concerns the private decisions of consumers. In the short term, appeals could be an obvious solution.

- Release strategic stocks to the World-Food-Program: There would be the possibility to partially dissolve the strategic stockpiling in the EU (and in other countries) and to release it for the supply of developing countries. Ukraine has up to now supplied the UN’s World Food Program, i.e., the EU and the U.S. should jointly take steps to replace these supplies.

- If at all, make wise use of the Fallow Land within the CAP (the GAEC 8-debate)

Under EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), the obligation to provide 4% of arable land as fallow from 2023 could start later and lower the obligation in the short term and temporarily. This could lead to some expansion of production in 2023. Since we need to look at all ends to provide the quantities for developing countries, using fallow land is one realistic option, especially in 2022, however, the effects might be overestimated and the ecological costs are substantial.

First, this measure is not relevant for 2022, as this obligation first takes effect in 2023.In 2022, the rules of greening, which provide for 5% ecological focus area, still apply. This obligation can also be met through the cultivation of legumes. The German Minister for Food and Agriculture, Cem Özdemir (The Greens) has announced on 11.03.2022 to allow the use of fallow land for feeding purposes. So in a way, this option has been taken already and with low ecological problems, since the fallow-land is still existing, it is just harvested at the end. The problem is here, at which point of time farmers make this harvest. And the effect for the world food situation is marginal if at all.

Second: For the first year of the new CAP-period, 2023, the EU-Commission could start with a slightly lowered obligation of e.g. 2.5% of arable land as fallow land. There is still time to take this decision, since the main farmers’ decisions on what to produce 2023, are taken in September, so there is still time until May, to observe the effects of the war and to reduce this GAEC8-obligation.

In 2018, about 2 Mio. hectares of fallow land were set aside within the EU, about half of which was in Spain. Excluding Spain, the share of fallow land in arable land is ca. 2.1%. In Germany, we are talking about about 180 thousand hectares of fallow land, here the share of arable land is about 1.5%. Many fallow areas are located on the poorer arable sites, i.e. if these areas were taken into production, the yield would be below average and high-quality grain could not be produced on all of these sites.

In addition, this measure also has significant environmental disadvantages. The biodiversity and climate crises continue unabated despite the war in Ukraine. There are legal obligations to reduce the amount of greenhouse gasses (GHG) from the agricultural sector. The area of fallow land is one way to reduce GHG-emissions. Fallow land is also an effective measure for preserving biodiversity, protecting individual species and creating refuge areas. If these areas are missing, we might observe severe consequences. In this respect, a temporary lowering of the fallow obligation must be well weighed politically with the disadvantages described. A temporary lowering of the fallow obligation would not be without consequential costs.

Since cultivation decisions will not be made until the second half of the year, it seems sensible here to wait a bit, since the extent of the crisis cannot yet be fully predicted. This option can still be taken in May or June.

No roll-back in the Common Agricultural Policy

There has been much talk about a “Turning-point” in different policy fields, as the German government has initiated significant policy changes in many policy areas like military policy and the proliferation of the Ukrainian army. Some contemporaries suggested that this must now also be the case in agricultural policy. The environmental orientation of the CAP and the Farm-to-Fork strategy should be put to the test.

The farmers’ lobbies Copa-Cogeca repeatedly come around and suggest Europe should solve the world-food problem, regardless of the type of crisis: This was suggested in the Covid-19-Crisis 2020 and this time, the same. And again: We need to solve the short-term problems at the world-market. The Farm-to-Fork might not be right in all details, but it is a long-term strategy to make the agricultural sector more sustainable and environmentally friendly. Fully withdrawing the Farm-to-Fork strategy from the table and stopping the environmental measures of the CAP will not bring back any tonne of wheat in 2022. This narrative from Copa-Cogeca is always accompanied by the claim, environmental policies would be a kind of feel-good-policy. And indeed, we need to produce, but not at any ecological price. From a scientific standpoint, this just shows that farm-lobbies are following on a dangerous anti-scientific path.

The environmental crises are still urgent and the suspension of environmental measures could result in considerable environmental costs for society, but also for agriculture. Measures such as the obligation to provide fallow land or the requirements for crop rotation also serve to safeguard the production potential of European farms in the medium term.

Overall, these narratives launched by the farm lobbies are critical in that sense, that their main arguments seemed to be the world-food-situation, however, we know that the contacts to the feeding-industries are well and the calls from this side are loud. It deems inappropriate to put the looming food-crisis as an argument to lower the feeding costs for our competitive meat industry in Europe. Here, the simple suggestion is: Let the markets work, don’t interfere. The feeding industry will solve the problems themselves, this is not an issue to solve for policy makers.

Overall, the aim in this supply crisis must be to take effective measures in the short term and to weigh up conflicting objectives in a sensible way. Here, the focus should be on the short-term supply of food to developing countries in 2022 (… and not on the supply situation of the feeding-industry).

Some other sources:

- Stephan von Cramon-Taubadel: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – implications for grain markets and food security

- Oleg Nivieskyi: Russian invasion in Ukraine could threaten global food security and starve hundreds of millions globally

- AMIS: Market Monitor Nr. 96, März 2022, Bericht des Agricultural Market Information System (AMIS)

- Linde Götz und Bettina Rudloff: Ukraine-Krieg und Ernährungssicherheit: Umsichtige »Food First«–Strategie für den Herbst entwickeln

More

3 Trackbacks / Pingbacks

Comments are closed.