On June 1st 2012, equivalence between US and EU organic standards was introduced. Without a substantive trade agreement between the EU and US, this was never going to amount to much.

On June 1st 2012, equivalence between US and EU organic standards was introduced. Without a substantive trade agreement between the EU and US, this was never going to amount to much.

Now however, with the ongoing Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) talks, this is no longer the case. This has the potential to make organic equivalence a lot more relevant, as it could foster a large increase in trade between the two regions.

Already trade has opened up. Banned since 1997 European beef can again be sold in the US. Internal EU organic beef salves are a significant part of organic trade. And while the US market may open up for Europe, the reverse is also true – US organic beef on the shelves in Europe.

Trade gains from TTIP for the EU have been estimated at between 60 and E120 billion per year. While high, this is dwarfed by other opportunities for the EU. These include “completing existing internal market in goods and services: worth 235 billion euro per year” according to the recently released European Parliamentary Research Service report ‘Mapping the Cost of Non-Europe 2014-2019’.

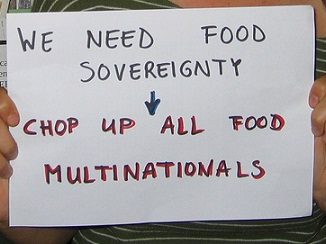

Others are more cynical about TTIP gains. Organisations including the Corporate Europe Observatory point to the “unfounded promise of increased trade and job creation” as well as an “attempt to reverse social and environmental regulatory protections, redirect legal rights from citizens to corporations, and consolidate US and European global leadership in a changing political world” as concerns.

Concerns regarding regulatory protections relate to TTIP creating equivalence in standards. While Europe wants some sensitive areas to be protected, including some but not all parts of the agri-food sector, the US is pushing for very few barriers.

It’s easy to see why. With the important exception of banking, standards tend to be more protective of sectors, but also of citizens and the environment, in Europe. And in general, the TTIP could enable a race to the bottom, whereby wheresoever the rules are weak and the standards low, that becomes the default.

Equivalence would not only mean more products from the US on sale in the EU, it could mean US companies suing governments in the EU or suing the EU’s institutions for having different standards, or for introducing higher standards over time.

This might sound farfetched, but it is in fact already happening, in the US, the rest of the world and even in the EU. Corporations can and do sue governments for having or introducing high(er) standards of consumer or environmental protection, through a process known as ISDS – investor-state dispute settlements. The corporate logic is that expected profits are lost on their part.

As we highlighted in October last year, examples include the awarding of compensation to companies when landfills have been closed, the phasing out of nuclear power in Germany (which ‘cost’ potential suppliers) and the current threat by corporations to sue the EU for the partial ban on neonicotinoid pesticides.

So even when the democratic process discontinues certain practices, based on scientific evidence, it is becoming increasingly easy for corporations to sue governments or the EU for these changes. In part this is because the EU uses a precautionary approach to risk, whereas other jurisdictions do not.

From an organic farming perspective, the fear is that, with the TTIP, organic products will in the future come onto the European market with a mode of production not permitted in the EU. These may even carry the EU organic logo on them.

There are perhaps unexpected differences between the US and EU on organics. With the exception of animal antibiotic regulations, US organic regulations are generally lower than EU rules. However that rule is noteworthy – animals must leave the organic system if antibiotics are used in the US. In Europe, there are different rules, and indeed different countries have differing interpretations.

However as a general principle, when it comes to antibiotics, the European organic rules are far stricter than the European conventional farming rules. The EU organic rules demand longer withdrawal periods (twice as long) whereby the animal or its product (usually milk or eggs) cannot enter the certified organic food chain. So if the one off use of an antibiotic means conventional cows’ milk cannot enter the conventional food chain for 48 hours, for organic cows, use of this antibiotic would mean 96 hours before that milk could enter the organic food chain. However this process is only allowed twice per year – any more often than that and the animal is out of the organic food chain altogether. Any routinised use of antibiotics is also disallowed in organic – in conventional dairy, to use that example again, all cows at drying off time (finishing up of calves suckling, a time when infection is more likely) are treated with an antibiotic. With organic, its only if a cow gets an infection or is observed to be sick, that, with a Vet’s permission, the individual organic cow can an antibiotic. And again, two treatments and the animal is out of the organic system. So the organic farming rules in both jurisdictions are stricter than the conventional rules, when it comes to animals and antibiotics, but there are strictest in the US.

On the other hand, the use of antibiotics in fruits and vegetables in European organic standards is stricter than in the US. Differences in antibiotic treatments is reflected in the equivalence deal from 2012, as the previous link points to.

From a European perspective, crucially, the rules on housing are far stricter in organic in the EU than in the US. This is especially the case when it comes to red meat and milk, where EU animals have far more space allowable than US animals. Though controversial, more restrictive confinement is practiced and allowable in the US organic standards even for ruminants (i.e. cows).

Karin Heinze gives an overview: “the fear is that, with the TTIP, organic products will in the future come onto the European market whose mode of production is not permitted in the EU but which, thanks to the TTIP, can nevertheless carry the EU organic label. Whereas in the EU the the precautionary principle applies, meaning that every product has to be tested before being put on the market, in the USA the risk principle applies, meaning the precise opposite, namely that the risks of a substance have to be proved before it can be banned”

She also points to seeds issues too: “harmonizing the regulations on seed would have devastating consequences for Europe’s farmers. The so-called farmers’ privilege, that allows European farmers to use farm-saved seed, is largely unknown in the USA. If this privilege is no longer in place, Europe’s farmers will be forced into even greater dependency – like the dependency US agricultural corporations have already forced on numerous third countries at the expense of freedom and the loss of worldwide biodiversity.”

That specific antibiotic rules restrictions were put in place in the 2012 organic regulation equivalence agreement is important, and a positive sign that adjustments can be made to these sorts of agreements, based on genuine difference and concerns over different standards. In this case, both regions got to maintain their higher organic standard. The problem is that TTIP is about doing away with those kind of differences. How will the 2012 agreement’s provisos fare in a post-TTIP world? Will they be respected, or seen as an opportunity for a two sided race to the bottom, spurred on by Corporate power?

So with TTIP negotiations ongoing, and despite the undoubted flaws and subterfuge in the system the organic sector would do well to contribute to the EU Commission’s TTIP consultation, which closes 6th July. After all , were it not for civil society pressure, it is unlikely that this consultation would have been initiated.

The TTIP treaty is a violation of democracy.

Why are the meetings so secret?

The corporation will have theright to sue a government!!! This is UNACCEPTABLE. I believe in organic food but also believe in SHARING. This treaty will transform normal life into an enduring blackmail.

Crap american food will be (chlorine chicken, hormones beef, GMO and in general food with high pesticides content) easily available in Europe. They have no real food culture, in the US eating is like filling your petrol tank. We have geographical and qualitiy denominations and labelling is very important. In the US they have nothing like that.

And don’t forget about the TISA, privatizing all services including WATER (Mediacl system, public school, transport, energy….etc. etc.)!!!!!!

TTIP, TTP and TISA are a crime against freedom, democracy and free expression. Our presidents didn’t even ask us about it, they didn’t even say anything about it. The EU people HAS the right to say NO to this and our presidents MUST listen to us. If they don’t what’s left of democracy will be dead.