How realistic is the Green Party demand in the current coalition talks for an agricultural turn, including the phase out of factory farming in 20 years? In the land of the near ubiquitous bratwurst, main ingredient in Germany’s number one fast food currywurst, how strong is the undercurrent of opposition to factory farmed pork and poultry?

How realistic is the Green Party demand in the current coalition talks for an agricultural turn, including the phase out of factory farming in 20 years? In the land of the near ubiquitous bratwurst, main ingredient in Germany’s number one fast food currywurst, how strong is the undercurrent of opposition to factory farmed pork and poultry?

Certainly, there are many signs of this discontent. Each January Berlin hosts the International Green Week, an agricultural trade fair. Year-on-year it has been accompanied by protests as thousands, many adorned in pig costumes and sitting in tractors, assemble outside the Fair’s entrance.

Wir haben es satt! (or We are fed up!) calls for an end to factory farming and a switch to more a more sustainable food system.

ARC2020 has been involved in this every year, and in other actions related to factory farming, including a 7000 person protest at the biggest chicken slaughterhouse in Wietze in 2013. There those gathered formed a human chain around the 40,000 bird processing unit.

See Summer Camp at Wietze 2013 (facebook photo album)

Demonstration at Wietze 2013 (facebook photo album)

Over the past few weeks, these concerns have been thrust into the limelight once more as Germany’s agricultural policy has become a controversial node of the coalition talks taking place at present.

Since the general election on the 24th September this year, complex coalition-forming negotiations have been ongoing. The currently leading Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and their southern counterpart the Christian Social Union (CSU) are in talks with the Free Democratic Party (FDP) and the Green Party to work out the details of a potential so-called ‘Jamaica-coalition,’ named after the respective party colours. The negotiations thus far have made little real progress, as the parties try to navigate competing interests and aims.

Key opposition exists between the CSU and the Green Party. The CSU, primarily supported by the rural South, advocates support for conventional farming, digitalisation and the opening of a Ministry for Rural Affairs. The Greens, more strikingly, are calling for an ‘Agrarwende’ or agricultural turn. A core part of this is the phase-out of factory farming within the next 20 years. They want to implement higher animal welfare standards by law and better certification systems for all animal products, with the widespread growth of organic farming as part of this.

Anton Hofreiter, leader of the Greens in the parliament recently published a book called Fleischfabrik Deutschland – Meat Factory Germany. He noted that paradoxically, Germany is producing ever more meat while consuming less. Instead, it is exporting more of this meat, while loosing farmers to the land and wages in the sector

98% of meat consumed in Germany comes from Massentierhaltung. This is ‘mass animal rearing,’ and refers to a husbandry strategy with vast numbers of animals usually squeezed into a very small space. It may be best translated as large-scale factory farming. As the meat industry became increasing export-oriented, meat prices were driven lower and lower. Currently the market price for 1kg of pork is €1.75 in Germany.

Factory farms in Germany hold up to 5,000 pigs in a single pen or 40,000 chickens per coop. That translates as each pig having 0.75 square meters and more than 20 chickens per square meter. Per year, Germany holds 12 million cows, 27 million sheep and 114 million chickens in such conditions.

These farms have a quick turn-over rate as the meat industry churns out around 753 million animals a year. Europe’s largest chicken farm sits in Wietze, just north of Hannover where over 2.6 million chickens are killed a week. That is between 7 and 8 per second.

Barbara Unmüssing from the Heinrich-Böll Stiftung spoke to the Süddeutsche Zeitung about the shift in German meat production, ‘In the last 15 years, 80% of farmers have given up rearing animals and yet Germany produces 50% more meat.’ This indicates a change from small farmer-run animal husbandry to fewer, large-scale businesses which dominate the market.

Anti-factory farm sentiments, previously concentrated on societal fringes in environmental and animal welfare activist circles, have gained prominence in mainstream media and public discourse. The number of vegetarians in the country increased from around 1.6% in 2008 to roughly 4% now. A 2010 study from the University of Göttingen shows that 20% of consumers would be willing to spend more for “good meat.”

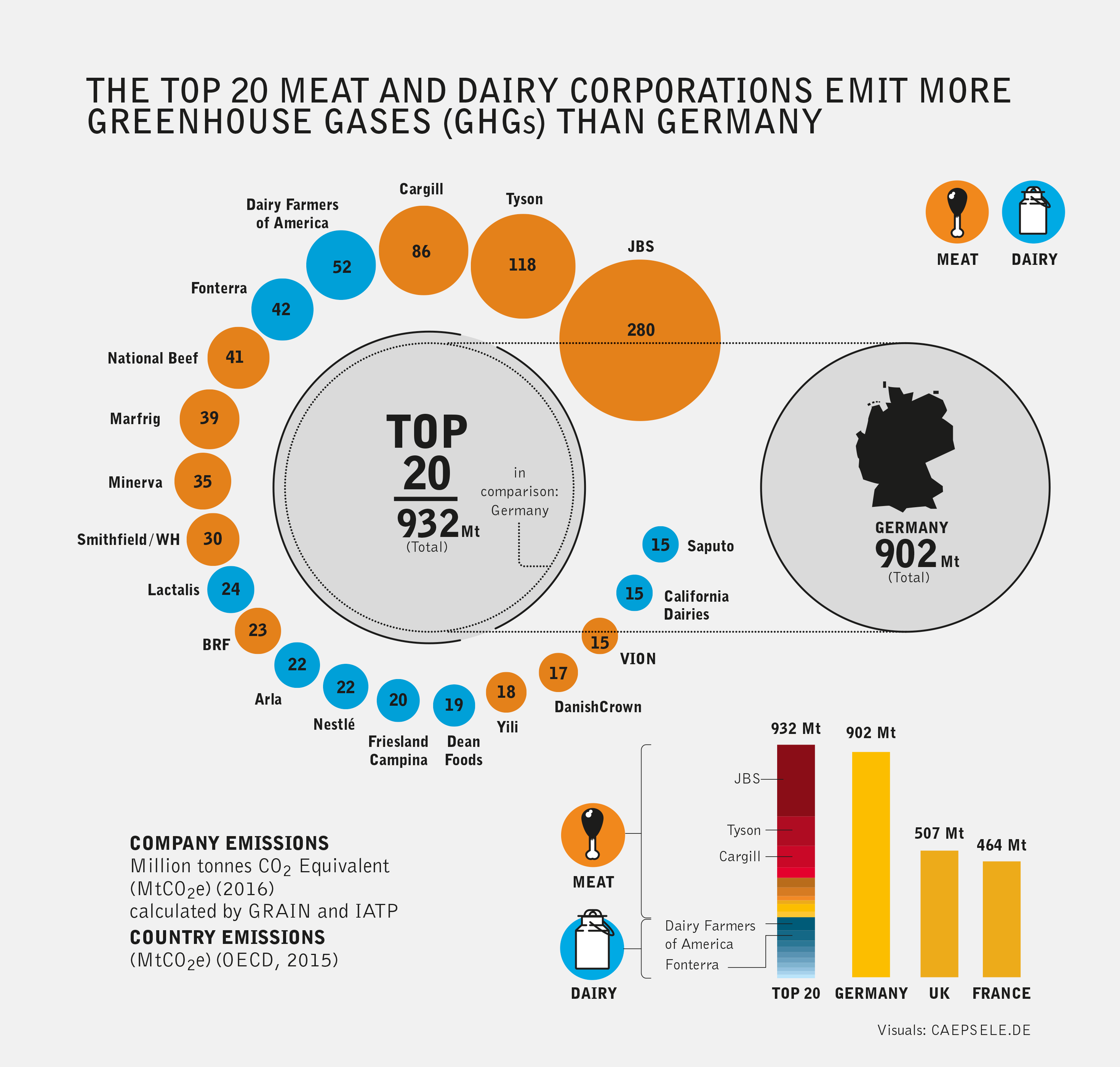

The arguments against intensive meat production are well-known and revolve around environmental impact, animal welfare concerns and human health effects. A recent study highlights the contribution to greenhouse gas emissions by large meat and dairy corporations. Taken together the top 20 meat and diary companies emit more greenhouse gases than Germany. Globally, livestock rearing accounts for about one-fifth of greenhouse gas emissions.

Animals which are so tightly packed over such a small space breed a host of unpleasant diseases and has led to worrying reports of cannibalism and other unusual behavioural patterns signally animal stress. To combat the spread of these diseases, antibiotics are widely used with recent EU findings of rampant overuse to the detriment of human health.

None of this is new. What is new is that a phase-out of factory farming is being proposed at the government level. Whilst there is reason to believe that it is unlikely that this will pass – the Green Party has already had to make significant compromises in the coalition-negotiations – the proposition in itself is significant and does not stand alone as an anti-meat industry initiative in the political sphere.

Back in 2015, the Scientific Advisory Board of the Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture submitted a report entitled ‘Pathways to socially acceptable livestock husbandry in Germany.’ They concluded that factory farming on the current scale is unsustainable in terms of animal welfare and achieving climate goals. It proposed a series of regulatory mechanisms, guidelines and recommendations for how the agricultural sector may be appropriately changed. This was met with widespread support within political parties and stakeholder groups but received little support from farmers unions.

The German Environment Ministry took the controversial step in February of this year to take meat and fish off the menu at all official functions. It was not an approach adopted by other ministries and was seen by many as a worrying sign of state paternalism. Nonetheless it again opened the conversation around sustainable meat production and consumption at the government level and raises questions about regulation versus consumer choice.

Public opinion is changing and this is increasingly reflected in political circles and mainstream media. For those advocating for an end to factory farming these are exciting developments. It remains to be seen whether these hopes are actualised in the coming years and whether Germany may lead other European countries into a similar direction.

Public opinion is changing and this is increasingly reflected in political circles and mainstream media. For those advocating for an end to factory farming these are exciting developments. It remains to be seen whether these hopes are actualised in the coming years and whether Germany may lead other European countries into a similar direction.

Helene Schulze has just completed an MSc Nature, Society and Environmental Governance from Oxford University. Her dissertation focused on seed saving. She helped organise the 2017 Oxford Food Forum. She has also interned for Sustain: Alliance for Better Food and Farming.

1 Trackback / Pingback

Comments are closed.