The expensive British exception will end with Brexit. But that won’t make it cheaper for everyone else, as London has been a net payer into the EU budget

A mini-Brexit took place back in 1985 with the UK budget rebate, which violates the principle of solidarity in European integration. But the payments made to farmers under the Common Agricultural Policy are hindering further threats of withdrawal from the European Union.

By Dietmar Bartz

“I want my money back!” exclaimed Margaret Thatcher, the Conservative British Prime Minister, at a summit of the then-European Community in 1984. Because the British farm sector was comparatively small, it could not benefit from subsidies from Brussels to the same extent as its counterparts in France and Germany. At the start of the 1980s, more than 70 percent of the Community’s budget went to agriculture, leaving no room to compensate Britain for its disadvantage in other ways.

Download the Agriculture Atlas: Agriculture Atlas 2019

But it wasn’t just agriculture. The United Kingdom was also disadvantaged by the relatively high customs and value-added tax revenues, on which each country’s contributions to the European Community were based. On top of that, as a result of a severe economic crisis, the British per-capita income was well below that of Germany and France. Mrs Thatcher had complained about the level of British contributions to the Community budget ever since she became prime minister, and stage-managed a political blockade in Brussels.

She won that battle – she got her “British rebate”, as it quickly came to be known. Two-thirds of Britain’s net contributions to the budget were nullified. For example, if the UK’s annual contribution amounted to 10 billion euros, and 7 billion were returned to the UK in the form of subsidies and grants, that would leave 3 million that the UK would have to pay to the common EU pot. The rebate meant that the UK instead needed to pay only 1 billion euros. The 2-billion-euro shortfall had to be (and still is) made up by the other member states. Agriculture was therefore the cause of the first major breach of the solidarity principle in Europe’s integration.

Such politics of a “fair return” or of giving with one hand and taking back with the other, met with fundamental criticism in Brussels. For it violates the community ideal – and anyway, what would be the optimum: for each member state to get back exactly the same amount as it had paid in? There is no way to calculate the various economic advantages and disadvantages of each member state, from investments to jobs to trade – especially if agriculture, with its variability in output and prices, is supposed to be the basis of such calculations.

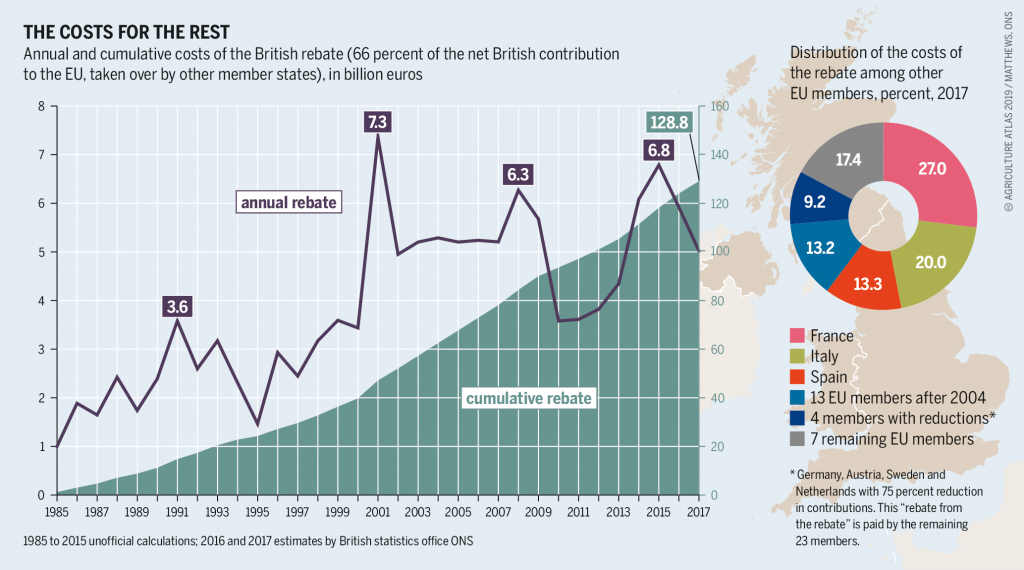

Nevertheless, no one in the EU has been able to get rid of the British rebate, despite the fact that the British economy has caught up with other industrialized countries, and the government switched to Labour. For the rebate has always been around: Since 1985, the EU budget has not been adjusted to take into account the reduced payments from the UK; instead, the other member states have had to make up the shortfall – including the newer and poorer members. In 1985, the rebate amounted to one billion euros; by 2001, it peaked at 7.3 billion. By 2017, the cumulative rebate totalled 129 billion euros. With Brexit, the rebate will finally disappear.

If Germany, France or Italy, the other big net payers to the EU budget had acted in the same way as the UK and had insisted on pursuing its own interests, the European project would have died a quick death. Ironically, the fact that the dispute over net contributions did not spread further is also connected to agriculture. In the early 1980s, farming in Europe was a bottomless pit – misguided incentives in the form of price guarantees led to market distortions and over-production. This longstanding crisis went far beyond Mrs Thatcher’s rebate. New integration initiatives generated a positive dynamic: the internal market, the common currency, support for infrastructure development. Although the Common Agricultural Policy remained the biggest budget line, agriculture faded into the background. The arguments now focused on reforms of the whole, ever-expanding EU, not the British rebate.

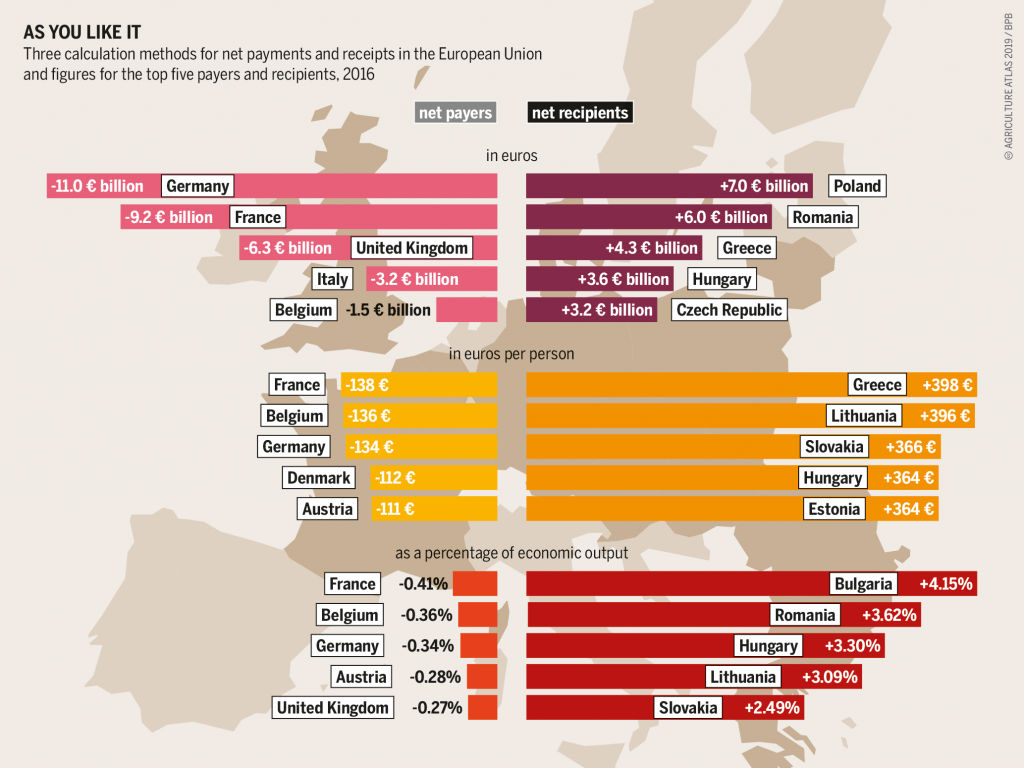

The economic costs and benefits of an EU membership are hard to quantify, but the financial situation is clear

The economic costs and benefits of an EU membership are hard to quantify, but the financial situation is clear

Nevertheless, the Common Agricultural Policy is important for the thirteen new member states that have joined the EU since 2004, most of whom are net recipients of the EU’s agricultural policy. Even governments that are critical of Brussels cannot afford to do without it – a fact both sides are very well aware of. For Poland, a European Commission draft has allocated a total of 30.6 billion euros for the budget period from 2021 to 2027. For Hungary, a smaller country, it still amounts to 11.7 billion euros.

On the other hand, the Commission wants to reduce its investment grants to Poland and Hungary – which are worth about as much as the agriculture payments – by about one-quarter. The payment of these funds will be coupled with the acceptance and integration of refugees. For agriculture, however, the governments in Warsaw and Budapest do not have to worry about such consequences: the Common Agricultural Policy is the same throughout the EU and remains a stable source of income. The most traditional sector in the EU – the funding of agriculture – is what helps to hold the Union together. Regardless of when Britain starts to look at this exercise in solidarity from the outside.

More from the Agriculture Atlas