We may never know whether it was poor food safety standards that triggered the Covid-19 outbreak. Regardless, the food industry is being turned upside down. The pandemic has hit pause on business as usual. As the Achilles’ heels of the current system are exposed, food sovereignty becomes an urgent question. Igor Tomasz Olech examines the butterfly effect on supply chains and trade routes.

China

In the wake of the Covid-19 outbreak, the Chinese lockdown has devastated demand – and prices. As more and more Chinese cities isolated and restaurants closed, the gastronomic industry stopped buying food. McDonald’s and Starbucks suspended their operations in China in order to reduce risk to their employees and customers. The meat industry and, indirectly, the animal feed industry have suffered the most – similar to the SARS outbreak in 2003. To compound the crisis, the outbreak coincided with Chinese New Year celebrations.

The Covid-19 pandemic also came on top of the African Swine Flu crisis. China was forced to kill millions of infected pigs, which also decreased demand for soy, thus feed producers were struck twofold. This eventually impacts global commodity markets.

Germany

German exports of meat, milk and beer to China have already suffered from closed trade routes and reduced consumption. The cold stores are already full of German products. Problems with liquidating production may force dairy producers to pivot towards dry products, e.g. powder milk. Closed trade routes will of course lead to a drop in global milk prices.

Some harbours are charging additional fees for storing massive amounts of produce due to overloads in warehouses. Buyers are backing out of purchases as they wait for prices to drop further. The shock to producers is amplified by the fact that demand for milk in China and Indonesia had grown over the past year, driving up prices by 20% or more. And China will not be the last dairy buyer to be lost.

Oil has also experienced a price slump due to failing supply chains. Consequently experts predict that oil producing countries will import fewer dairy products. Of course, oil prices are also influenced by political games which we won’t go into here. Nevertheless, these factors together with the virus seem to add up to a perfect storm. It is not clear whether an expected decline in Dutch milk production (due to new limitations on manure usage) will save German milk exporters from turbulence.

Not only German exports are under threat. In the early days of the outbreak, German consumers were concerned that imports could bring in the virus. German agricultural minister Julia Klöckner has since confirmed this is not possible, while also later announcing plans to to fly in migrant workers. As we reported here in recent days: “On April 2, 2020 the German Ministry for Food and Agriculture (BMEL) announced a travel strategy to overcome the labour shortage. The ministry proposed a set of rules to allow about 40,000 seasonal workers to travel by plane to Germany in April and again in May, which could cover a substantial part of the 100,000 workers needed in May.”

See below this article for two detailed pieces by Sebastian Lakner on the situation in Germany and the EU.

USA

Not only has the stock market massively declined due to the coronavirus, commodity markets have also shrunk, possibly due to supply chain delays. CNBC has sounded the alarm that wheat and corn futures are falling (although in recent days they recovered to prices from three months ago), and investors are moving to safe havens such as gold. Here we can clearly see that it is not solely about stable food supplies, and a globalized market does not necessarily mean food security – especially when investors put their financial interests first.

According to Reuters, the cheap Brazilian real and Russian rouble will drag down prices of wheat and soy, which will hit American producers. In response the Fed has lowered interest rates (as during the last crisis) and may introduce quantitative easing to support quarantined citizens. The actions of the American central bank may enable American farmers to compete with Brazilian and Russian producers on the global market. But the resulting inflation will be to the detriment of the entire national economy.

Besides that more questions arise: why do American producers have to produce so much in order to have their labour financially compensated? And when they produce so much, why must they let the price of their produce be dragged down by competitors, who actually mirror their behaviours in global markets? The World Trade Organisation has unsatisfying answers to these questions. The trade system is overloaded with complex mechanisms. People will not stop eating, but their eating will be impacted by networks which can be easily crushed by an unexpected event. Brennan Turner, an agricultural analyst, wrote on his blog:

(…) the coronavirus impact on grain prices has been immediate on the futures board (and thus, cash markets), but demand for agricultural goods in China hasn’t necessarily declined. What has declined, however, is the optimism that a globalized trade network will be able to function as it has normally for the last number of decades. Think about it this way: how many things that you either use today or buy on a weekly basis are made in China?

Americans, like Germans, are also having problems exporting to China. US products are not being shipped directly to Chinese ports, but to the ports of neighbouring countries. For example, the US Poultry & Egg Export Council has announced that frozen chicken cargos are being stored in ports in Vietnam, Hong Kong, South Korea and Taiwan.

Russia

Russian supermarkets have stopped selling Chinese fruits and vegetables. One of Russia’s largest retail chains, Magnit, explained that the cause is not only the risk of the virus spreading, but also logistical problems. Magnit has already started importing vegetables and fruits from Morocco, Turkey and Israel, and has stepped up purchases of domestic produce. However, the weakening rouble makes it difficult to find alternatives. Another retailer, X5, imports garlic and ginger from China but has not yet observed any logistical problems. Both supermarkets claim the current crisis will not affect retail prices, although Vladivostok and the east of the country have already experienced fruit and vegetable shortages.

Prior to the Covid-19 outbreak, China supplied 11% of vegetable imports to Russia (1 in every 3 cabbages, 1 in every 4 carrots, and 1 in every 5 cucumbers) and was importing 22% of Russia’s vegetable produce.

Russia has also closed its borders for Chinese workers. Pre-Coronavirus, tens of thousands of workers would come to Russia from China. This year alone, 33,000 employment permits were issued, primarily in the Far East. Agriculture is the third most popular sector for Chinese workers, after construction and trade. Five percent of Chinese immigrants work in agriculture, mainly as tractor drivers, agronomists and vegetable growers. However, in some places, such as the Primorje Territory, there is a total ban on Chinese employment from 2020. Chinese workers are now to be replaced with Uzbeks and Tajiks.

Russian cereal exports, and indeed those of its neighboours, have been restricted in what could be seen as a re-regionalising cereal supplies.

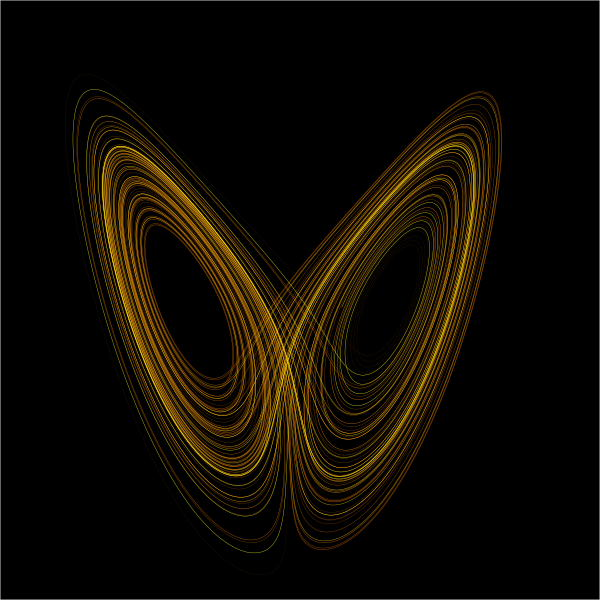

Butterfly effect

In our world of global networks and complex supply chains, a black swan event produces a domino effect, or a butterfly effect. The butterfly metaphor is used in chaos theory to describe how a small event can have huge consequences: the flap of a butterfly’s wings can cause a tornado.

Coronavirus has exposed the weaknesses of the current system in multiple ways. The crisis has emanated in different forms in different countries, and is affecting trade across the board. The impacts we have seen so far will be experienced by most countries to a greater or lesser degree:

- Imports and domestic consumption

In China the lockdown led to a decline in consumption, which impacts on meat and feed prices, and on meat producers.

- Exports and warehousing

In Germany dairy sales have slowed, and producers have had to change their production patterns.

- Markets and food security

In the USA the commodities market is going through turbulent times. The stability of food prices is compromised by the financial security of investors. Broken supply chains are impacting the markets, and potentially food security.

- Retail and labour

In Russia the virus is impacting the retail sector and labour, which is essential for the world’s biggest wheat producer.

We’ve already seen how the Covid-19 outbreak is changing eating patterns. Sales of dry and canned foods have skyrocketed. Instant soups of are flying off the shelves. If access to fresh food is jeopardized, entire countries could become food deserts. Only time will tell if we are facing down a near-apocalyptic scenario. The current crisis begs the question: is profit-driven food production still profitable?

More on Covid-19 and supply chains

Effects of Coronavirus on Agricultural Production – a First Approximation (part 2)

Effects of Coronavirus on Agricultural Production – a First Approximation

Framing Farming – Nationalism, Food Security and Food Sovereignty

UK | Coronavirus: Rationing Based on Health, Equity and Decency now Needed

UK | Coronavirus Diary: the Virus That Did a No-Deal Brexit on our Food Supply

Coping with Covid19 – Commoning as a Pandemic Survival Strategy

Council of Ag Ministers meet on Covid19 | Green Lines, State Aid, CAP Extension

Coping with Covid19 – Tensions in Farming, Trade and the EU Institutions

Coping with Covid19 – the Open Food Network and the New Digital Order(s)