Special guest post by Dr. Sebastian Lakner, Research Associate at the Chair for Agricultural Policy at the Georg-August University Göttingen. This post originally appeared on Sebastian’s blog.

How are farmers implementing Greening 2015 and which options they would choose in order to comply with the criterion of the ‘ecological focus area (EFA)’? The main message was that farmers would probably prefer to use the options of catch crops, nitrogen-fixing crops and fallow land, since they provide cost-advantages against the classical biodiversity options such as buffer-strips and landscape elements. This expectation was also based on the fact, that the latter go alongside with legal insecurity. In addition, structural policies and the practice of direct-payments before 2013 lead to a situation, where farmers would rather exclude landscape elements from their registered farm land. Overall, the expectation was that landscape-elements and buffer-strips (as the most effective options to support biodiversity) would hardly be chosen by farmers.

In May, the EU-Commission published a detailed report on the implementation of the CAP-reform. Most of EU-member-states (MS) have offered a number of EFA-options (see a report from the EU-commission on the CAP-reform implementation), 14 MS are offering 10 EFA-options and more, 9 MS are offering between 5 and 9 EFA-options. Only in 5 MS the choice is restricted to max. 4 EFA-options. So the choice within most member-states is quite broad and it is going to be an interesting topic to observe how farmers finally decide.

Development of legumes and fallow land in 2015

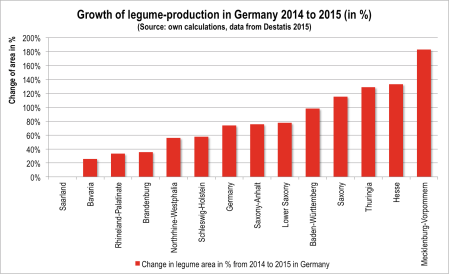

During this summer there were some press-releases and reports were published, that document the impact of ‘Greening’ on farms in Germany. On August 03, 2015 the Federal Statistical Office of Germany (Destatis) published some preliminary production data. According those data ‘Legumes’ (74%) and ‘Fallow Land’ (+62%) have drastically increased in Germany. The following fig.1 shows the increment of legumes from 2014 to 2015.

The main production area are in Eastern Germany and Hesse with shares between 2% and 3% of the total arable. In contrast, in most western states we find just shares of 0.5%. In Eastern Germany this can be explained by economies of scale, i.e. larger average farm-size and the available harvesting machines for harvesting legumes. Appropriate machinery and harvesting techniques are important, since harvesting legumes is often regarded as one of the main problems in legume-production.

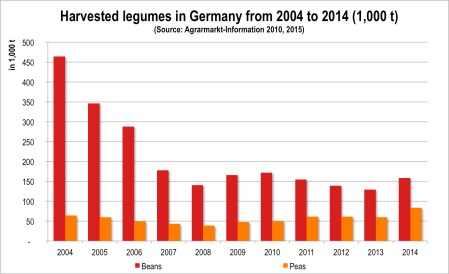

However, the impact of Greening is only a turn-back to the shares of the mid-2000s. At the moment, legume production has reached almost the level of 2005 (95%). Since 2004, the production mainly of beans has drastically declined (as shown in fig. 2):

A similar effect (+62%) can be observed on fallow land, which has been decreasing after the ‘Health-Check-Reform’ 2009. And here again, the shares have been substantially higher in the mid-2000s: The share of fallow land is just a 37% of the share in 2005.

Overall, my expectation would be that the observed growth of legumes won’t be sustainable. If Greening gives incentives to produce legumes and ‘fallow land’, farmers will follow, especially because other options are much more costly. However, as soon as those incentives fall, the shares of legumes and fallow land might decrease again.

Any market impacts of Greening?

In addition, it is unclear how the market-equilibrium of legumes is affected by Greening and how supply and prices of beans and peas develop. If all legumes are finally harvested and processed, we might observe and oversupply and prices might drop substantially. The price of legumes is displayed in figure 3:

So far this does not seem to be the case: During the summer we could observe prices for peas and beans of 150-185 €/t, which is still above the low level of the years 2009/2010. During this low-price period prices use to reach a low level of 100-140 €/t. The price-drop of legumes after harvest 2014 until Sept. 2015 is rather due to the general decreasing price-trend on the world-market followed also by legumes. It might be that a share of farmers finally did not harvest the legumes and rather used it as a green nitrogen-fertilizer and that some of the produced legumes are not appearing as supply on the market. (But this is just speculation.)

Reports of Ecological Focus Area in Lower Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt

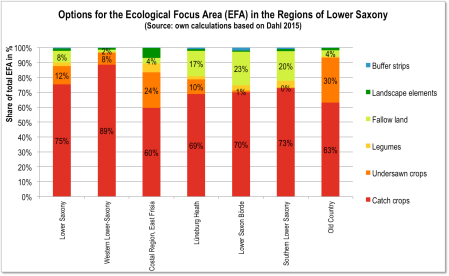

The Statistical Office of Lower Saxony has also published detailed data on the registration of Ecological Focus Area (compare Dahl 2015, in the monthly statistical report 08/2015). The data document that fallow-land and catch-crops are the most important option chosen by farmers in Lower-Saxony (See fig. 4):

Fallow land and catch crops take 95% of the total EFA in Lower Saxony. The high share of catch-crops is not surprising. For catch crops it is necessary to use a summer-crop, mainly with sugar beet (which has a high share in Lower Saxony) catch crops are useful, because it also avoids soil-born diseases and nematodes. According our calculations (published in Natur & Landschaft in June 2015) catch crops have the lowest costs of all EFA-options.

Dahl has prepared the same data for six production regions in Lower-Saxony (11 of all counties don’t belong to those regions):

Tab 1: Production Regions in Lower Saxony (Dahl 2015)

| Region | Main type of farming |

| Western Lower-Saxony | Pig- & poultry production |

| Costal Region, East Frisia | Milk farming |

| Lüneburg Heath | Potato-production |

| Lower Saxon Börde | Arable farming |

| Southern Lower Saxony | Arable farming |

| Old Country (between Hamburg & Bremen) |

Fruit-production, milk & mixed farming |

The following fig. 5 show the regional reports of Ecological Focus Area (EFA):

We can see, that decisions in the regions vary substantially. We can observe high shares of fallow land in the arable regions ‘Börde’ and ‘Southern Lower Saxony’. However, this might be due to small sizes of land plots. And within the respective counties, there are plots with lower productivity, where fallow land is then applied. Under sawn crops are mainly chosen in regions with a higher share of grassland (‘Old Country’, ‘East Frisia’), which can obviously be combined with the production of fodder-grain. A similar statistics on EFA in Saxony-Anhalt gives a different picture (Fig. 6):

This is fully consistent with the statistics above: Farms in East-Germany are using the option of legumes, which take a share of 24% – in contrast in Lower Saxony, where legumes have only a share of 2.4%. This might be explained by economies of scale: The average farm size in East-Germany is larger and farms also have better harvesting techniques.

Conclusions

Overall, the share of landscape elements and buffer strips is very low, around 2% in both states. Landscape elements and buffer strips could be the most effective and useful options to support the maintenance of biodiversity in agri-ecosystems. However, this options as almost not chosen.

- This might be explained by the recommendation of the official advisory services to register mainly catch-crops, fallow land and legumes for legal security reason.

- Legal issue and insecurities, and in East Germany fragmented land-ownership might explain the low use of landscape elements. If e.g. hedges are used for EFA, the diverse land-owners of this hedge need to accept this options, which might cause problems and a lot of communication and transaction cost.

- Structural policy and the control practise of cross-compliance have rather given incentives for farmers, to exclude landscape elements form their core-farmland and sell it to the local communities. Therefore, a lot of farmers do not own their former landscape elements anymore.

- Finally, planting a new landscape element is (probably) the most costly options to comply with the ecological focus area. The greening component (87 EUR/ha) is not enough to cover investment- and maintenance-costs of landscape elements. Therefore, greening is not the appropriate measure to support landscape elements.

- Interestingly, the option of buffer-strips also has a very low share. Buffer-strips are sometimes also additionally supported by agri-environmental measures in the II. pillar. This sounds attractive, but in practice there are a lot of restrictions and requirements: e.g. in Saxony-Anhalt, this support of the II. pillar is restricted to only 2.5 hectares per farm. With an regional average farm-size of ca. 400 ha, about 12,5 ha would be necessary to comply with EFA. Therefore, this highly supported combination does not seem to be attractive for farmers.

Finally, these results are only the first round of 2015 and for two regions, where arable farming plays an important role. I have picked those federal states, since biodiversity indicator show that landscape deficits are high especially in the main arable regions (‘Börde’) of those two federal states. The results for the states are rather poor. It will be interesting to investigate other regions as well and to observe the development during the next years. However, a substantial increment of landscape elements and buffer-strips from my point of view doesn’t seem to be very realistic.

The figures document that farmers react according the general expectations and incentives and they use the given production option of Greening. A moderate small impact on biodiversity might still come from fallow land, however, overall Greening shows to be mostly ineffective to protect biodiversity. The EU-commission and the supporters of the greening-concept need to answer questions, such as how we can justify the greening-component of 1.5 Billion EUR per year in Germany, which has little effect on biodiversity and windfall gains for farmers between 70% and 90% of the greening component. Even the most severe measure, the ‘ecological focus area’ seems to show almost no effect on biodiversity, but restrictions for farmers entrepreneurial decision and a substantial amount of administration for both farmer and state.

Special guest post by Dr. Sebastian Lakner, Research Associate at the Chair for Agricultural Policy at the Georg-August University Göttingen. This post originally appeared on Sebastian’s blog.

Update

In his blog post of 8th October, Sebastian Lanker, using data from the German Ministry for Food and Agriculture , which essentially confirms what is in the above article.

This update reports very little biodiversity impact from EFAs. German farmers have opted, by and large, for production options:

Catch crops and under sawn crops are the most important options (68%), followed by fallow land (16%) and nitrogen fixing plants (12%). The two interesting options for biodiversity and ecosystem-connectivity, buffer strips and landscape elements have a share of only 3.6% of the ecological focus area. But to see the full effect for agro-ecosystems, we need to see the share of buffer strips and landscape elements to the sum of arable land, which is 0.42%. This is from a biodiversity perspective simply disappointing….

If we argue with the efficiency of tax-payers money, the payments in agri-environmental are more efficient to support biodiversity services from farmers. The actual data on greening bring a lot of arguments to lower the level of direct payments in pillar I. and increase the financial volume of the agri-environmental programs in pillar II.