Thanks in part to the gloves-off approach of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – the IPCC – finally climate change is breaking into the news in a more sustained manner. A 12 year deadline for meaningful climate action and the emergence of strident climate change denying global leaders has focused the minds of many.

From an agricultural, food and rural perspective, livestock and its role in climate change is crucial. And if ever there was an example of two silos developing, its in the area of livestock and climate change. Or, if you prefer, the regen vs vegan argument.

Regenerative approaches to farming typically integrate livestock into the farming system. Sometimes these approaches primarily focus on livestock, as in the case of mob or holistic grazing. Proponents see livestock as a vital cog in the machine of building carbon in the soil. These are not the only proponents of livestock from an environmental perspective – you’ll see many more below – but its a strong and specific argument.

This sits uneasily beside a growing meat reduction and meat rejection movement, which emerges as a climate change solution from numerous perspectives – academics publishing in peer reviewed publications, high profile journalists and huge, influential environmental organisations like Greenpeace.

We’ve broached this topic in our climate change, livestock and soil coverage at various stages over the last two years. Below is outlined lots of very recent climate change research, and more research and analysis as it relates to livestock. Many perspectives are considered as are the implications of changing land use in rural areas.

We can’t promise certainty, we can’t guarantee the merging of some silo thinking, but we can at least give you plenty of up to date information from worthwhile sources, in a curated article. There are very tentative conclusions below too.

The IPCC report

The most recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – IPCC – is of course very important, but it can be a little hard to actually find. Its rarely linked to in prominent articles, like this live one from the Guardian – or this timely article from the same source on the day of report publication. It also doesn’t seem to have a proper name, but is shortened to “IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5ºC” or SR15 typically.

So here it is. The IPCC’s own twitter account is good for finding the actual up to date versions of their publications. Here’s the IPCC page on the most recent report.

Of note

Soil is mentioned 118 times in this 792 page document. Here’s the first mention:

“At the local scale, soil carbon sequestration has co-benefits with agriculture and is cost effective even without climate policy (high confidence). Its potential global feasibility and cost effectiveness appears to be more limited.”

Drop most meat

From an agri-food perspective, much high profile new research emphasises the role of reduced meat reduction, and a corollary move to plant-based diets as a way to tackle climate change. Prominent among these is the Stockholm Resilience research, published in Nature. While ostensibly about “a global shift towards healthy and more plant-based diets, halving food loss and waste, and improving farming practices and technologies are required to feed 10 billion people sustainably by 2050” the Guardian reports that what this means for the west is “beef consumption needs to fall by 90% and be replaced by five times more beans and pulses.”

Of note

Most? Drop all meat!

A paper called The climate mitigation gap: education and government recommendations miss the most effective individual actions was published in Environmental Letters in 2017. It made some quite radical suggestions –

“We have identified four recommended actions which we believe to be especially effective in reducing an individual’s greenhouse gas emissions: having one fewer child, living car-free, avoiding airplane travel, and eating a plant-based diet.”

And considering the data, radical is needed.

The Oxford-based FCRN – Food Climate Research Network – are a very prominent and relevant research team. A very recent paper (officially published in December 2018!) calculated the carbon footprints of food supply across different European countries: “The share of animal products in the diet is the most important factor determining the footprint of food consumption. Embedded land use change in imports also plays a major role. Transition towards more plant-based diets has a great potential for climate change mitigation.”

What!? Don’t drop meat -methane, methods and mob grazing

Myles Allen and colleagues suggested in June a different way to think about – and to compare the impact of – the global warming potential of greenhouse gases. The important distinction is between methane which is “short-lived” and carbon, which is a “long-lived” climate pollutant.

“We don’t actually need to give up eating meat to stabilise global temperatures,” says Professor Myles Allen who led the study (meat production is a major source of methane). “We just need to stop increasing our collective meat consumption. But we do need to give up dumping CO2 into the atmosphere. Every tonne of CO2 emitted is equivalent to a permanent increase in the methane emission rate. Climate policies could be designed to reflect this.”

Allen’s college David Frame:

“Under current policies, industries that produce methane are managed as though that methane has a permanently worsening effect on the climate…But this is not the case. Implementing a policy that better reflects the actual impact of different pollutants on global temperatures would give agriculture a fair and reasonable way to manage their emissions and reduce their impact on the environment.”

While radical change is what is needed, the supposed misanthropy of the Environmental Letters 2017 publication above has been critiqued by researcher Frederic Leroy. Leroy is also in the habit of making really well constructed, good looking, well-referenced twitter threads on this and related topics:

This thread links to lots of really useful UN FAO and other research. The emphasis is on accurate counting of livestock’s GHG contribution and methane emissions’ true impact (and recent stabilisation in absolute emissions terms) when compared to Co2. In particular the positive impact of best practices in livestock management is spotlighted by Leroy – integrating legumes and trees, circular economy refinements, feed efficiencies, the climate change mitigation potential through soil organic carbon sequestration of adapted multi-paddock grazing – aka mob grazing. (This thread was also turned into an easy-to-follow ‘unroll‘.)

Leroy’s arguments bears similarities to October’s Conversation article by Mitloehner – who was one of the first experts to point to the huge flaws in the now infamous Livestock’s Long Shadow publication. This left its own extremely long shadow, as it used a full life cycle analysis of livestock’s climate impact – but did not do so for any other sector. As Mitloehner reminds us, this flaw was acknowledged by the Worldwatch Institute authors.

As often is the case, Mitloehner broadens out the perspective to other areas of sustainability, something that FCRN’s Tara Garnett acknowledges as being important.

And despite its very polemic yet casual opening style, this blog post by “Karin L” does ask some important agronomic questions of the presumptions inherit in the Stockholm Resilience research. In particular, it asks about soil, carbon, fertilizer, land use change(ability) and tillage. Simply put – not all grazing land is necessarily suited to conversion to other food production systems, especially to cereal crops and horticulture.

It is important to note that by soil carbon sequestration being left out of the Stockholm Resilience research, agroforestry and regenerative agricultural approaches could not be considered as they have too many uncertainties, when compared to environmental actions with official targets.

An obvious next question is – how are those official targets working out? How many of them are being reached? How realistic are they in the cold light of day?

Supposedly, it’s not realistic to consider livestock farming methods that have been shown to actually balance out GHG emissions in specific geographic areas, areas which have significant similarities to other areas regionally and all over the world. And yet these stated targets government’s set – but patently fail to reach – are fine to work from.

There is also so much going on under the ground, in terms of microbes and mycelium, water retention and climate resilience (adaptation to drought for example), that the proliferation of these mob grazing methods can be seen to have many positives worth further developing. Some but not all of these are considered in this challenging article by Andrea Beste.

Nevertheless…

Nevertheless, its important to note that FCRN researchers have considered many of these arguments and do acknowledge some of them, with caveats. Tara Garnett’s October 2017 piece for The Conversation, following on from the publication of Grazed and Confused deals with quite a few of them – especially in the (ongoing) comments.

As Garnett acknowledges “well-managed grazing in some contexts – the climate, soils and management regime all have to be right – can cause some carbon to be sequestered in soils. But, the maximum global potential (using generous assumptions) would offset only 20%-60% of emissions from grazing cattle…”. She also points out that the carbon sequestering benefits of grazing systems are temporary (eventually carbon is released) and volatile (eg via land use change), and that methane emissions may be short lived, but as long as livestock farming continues, and continues at the rate its expanding, methane emissions will too.

Indeed, the next decade or so is vital as the IPCC suggests, if we are to prevent runaway climate breakdown, so however short-lived methane is, its short-lived and ongoing in a very important period.

Garnett also points out that the risks of extrapolating out from small geographic regions to far wider areas – where different conditions may apply. So where there is positive research on mob, or, more formally, holistic planning grazing (e.g. by Teague, Conant) caution is needed – and the authors themselves also often point this out.

We also see FCRN researchers point out that most methane goes into the air and not into the soil, while the comment section of the Garnett article covers this and many other areas in some detail too, from more than one perspective.

And another nevertheless – some focus needs to be put onto how near complete reductions in both methane and nitrous oxide emissions from livestock are actually achieved right now. That the latter comes from multi species grasslands means there are multiple benefits beyond simple emissions, including climate resilience – and there are more significant questions again to the Irish authorities regarding the ending of these incredibly promising trials.

Moreover the scale of ambition is supposedly too high in many cases for these soil carbon measures to be rolled out on any level – yet we know serious ambition and radical change is required. This failure of ambition – despite evidence of positive soil carbon storage via certain grazing systems – is covered in more detail in this article of ours from March.

Next Steps – what else, if not meat?

Its difficult to manage the cognitive dissonance in current research. We hear that we must both reduce livestock radically and also that livestock is vital for broader sustainability, including also from a climate change perspective. To some extent, it appears the divide partly comes from researchers differing in specialisation – some are more agronomically embedded, in every sense, and concerned about likely land use change. The width of the sustainability focus – climate change only or broader considerations such as poverty and biodiversity – seems also relevant.

So let’s consider what else, if not meat.

Other edibles and their consequences

Permanent grassland holds previously ignored deep stores of carbon, and land use change towards other forms of agriculture threaten this. Cereal crops (often called tillage crops) – especially monocultural maize/corn production – are appallingly tough on soil, with lower and diminishing soil carbon levels and higher likelihood of soil being washed away. Horticulturalists, even the most mixed and agroecological of them, worry about how to bring fertility into their systems without at least some livestock manure. Even the most driven of proponents of dropping meat completely, such as George Monbiot, find it hard to find anything veganic scaleable, beyond impressive pioneering individual vegan farms. And some of the other sci-fi solutions for food bring us into very new territory to say the least.

It’s also worth remembering that many regenerative practices stem from the traditional organic handbook, produce mostly edible plants and don’t necessarily involve livestock. These include crop rotations, cover crops/mulches, companion planting, green manures, soil amendments, composting/compost teas, forest gardening, silvoarable agroforestry and more.

And there can be many other sustainability reasons to bring outdoor livestock into farming systems, and silvopastoral agroforestry remains chronically under supported despite obvious, compelling benefits.

It’s worth remaining focused on the fact that there is much to be said, from a broader sustainability perspective, for mixed agroecological farms, incorporating some livestock for fertility and other services, in well worked out bioregions where agroecology is a guiding principle. This would improve the overall climate change performance of farming and of said region – but with climate change as one of the variables, not as the single or dominant concern.

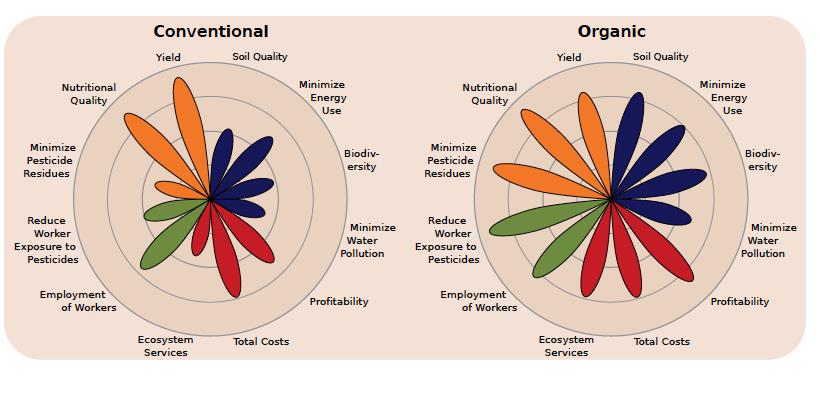

(This broader sustainability thinking is explored in more detail by Reganold and Wachter 2015, this time in the related case of organic farming (see image below) though in this case without reference to cliamte change specifically.)

It may seem outlandish to consider extrapolating the research of Teague and others on holistic management to the whole world: equally, it seems faintly ridiculous to talk about 90% reduction in beef consumption, or planetary plant-based diets, when billions of people rely on animals as part of a largely sustainable form of peasant agroecological farming.

Climate justice is retrospective too, and the bad behaviour of us in the west should not be used to recolonise and disenfranchise farmers in the global south.

Rewild it

Moreover, many regions won’t suit anything other than either rewilding or livestock – and the likelihood of rewilding leading to viable nature based economies (e.g. ecotourism) will vary from region to region – and have other unintended consequences.

For example, on the island of Great Britain, there are about 60 million people. Transitioning over to nature-based economies might well transform the uplands positively, leading to an increase in nature derived economic activity, some of which will be more viable than others. Chief among these could be ecotourism in new emerging mountain forests.

The island next door – where this author lives – Ireland, has about 10% Britain’s population and just under 30% the land area. Transitioning rural mountainous areas over to nature-based economies may work for some economic activities here, though thus far, monocultural spruce plantations has been the preferred (ecologically devastating) option. Nature based economies are also less likely to be as successful when it comes to ecotourism in Ireland – there are far fewer potential local tourists available. Unless, in this case, success is measured only in terms of economic activity derived from long distance visitors and not environmental (especially climate change) impact.

It is also very likely that, for every birdwatcher, as many again pursuing bloodsports – hunting, shooting and fishing – will come too. And this in itself will bring a raft of unintended consequences. And, meat to eat in the form of far more game than is consumed currently.

For ecotourism on the island of Ireland – the island off the other island off north west coast of Europe – would inevitably mean increasing longer distance tourism from Britain and the rest of Europe. This would be mostly by plane, or, in some cases, driving to Ireland via ferry. Ferries, despite on balance probably being a better choice environmentally, are not known for their fuel cleanliness or efficiency. And bringing the car – with or without other passengers and other baggage – may or may not be much better than flying to Ireland, compared to an individual with carry on bags on a full plane: its very variable and hard to work out as an individual traveler. I often travel of fairly empty ferries, and get fairly empty trains into rural Ireland.

What is easy to work out is that both however have a significant climate change impact – both methods have the unintended consequences of replacing sheep’s poor climate change performance with long distance, fossil fuel dependent travel to look through binoculars at the new animals that replaced the sheep. Or, to shoot them.

Thinking about what these visitors will eat adds further complexity. Whale meat consumption increased rapidly in Iceland when tourists started arriving by plane in large numbers for the first time, as this is what the visitors thought gave them the quintessential local experience. (There are signs that it may be declining again due to campaigning).

So maybe mountain forest berries will someday take over from Connemara mountain lamb as a sought after Irish delicacy…but that may take some time. Meanwhile, this author will try to take it all on board.

To eat mostly plants from the local community owned farm – the one that’s all veg but that uses animal manure – the odd foraged nibble from the edible landscape of the ecovillage and surrounds – and yes sometimes some thoughtful meat too.

More from ARC2020

#SoilMatters Part 3 | Soil, Carbon and Policy – where now for 4p1000?

Do we Have the Tools to Choose Sustainable Meat? #LivestockDebate

Biochar – the Ultimate Tool to Make Farming More Sustainable?

Recharging Soils with Carbon Could Make Farms More Productive

More reading

June 2018 Hannah van Zanten A role for livestock in a sustainable food system

This research tries balancing a climate or biodiversity perspective with a land and resource-use perspective:

“we suggest that the role of animals in the food system (referred to as low-cost-livestock) should be centred on converting biomass that we cannot or do not want to eat into valuable products, such as nutrient-dense food (meat, milk, and eggs) and manure…arable land should be used primarily for production of food crops, rather than for feed. Low-cost livestock then would not consume human-edible biomass, such as grains, but convert leftovers streams into valuable food, implying that production of livestock feed is largely decoupled from arable land….

to reach biodiversity conservation and carbon sequestration targets it is probable that grazing would need to cease on some of this land. Grazing ruminants also give rise to considerable GHG emissions particularly in the form of methane. These two observations suggest that the level of meat production that might be sustainable from a climate or biodiversity perspective might be lower then what is sustainable from a land and resource-use perspective; a ‘best-fit’ way through all this needs to be navigated and is an area that merits further research.”

April 2018 Helen Breewood Are modern plant-based diets and foods actually sustainable?

May 2018 Damien Carrington Avoiding meat and dairy is ‘single biggest way’ to reduce your impact on Earth

“while meat and dairy provide just 18% of calories and 37% of protein, it uses the vast majority – 83% – of farmland and produces 60% of agriculture’s greenhouse gas emissions. Other recent research shows 86% of all land mammals are now livestock or humans. The scientists also found that even the very lowest impact meat and dairy products still cause much more environmental harm than the least sustainable vegetable and cereal growing.”

June 2018 Vétérinaires Sans Frontières Avoiding meat and dairy: a one-size-fits-all measure to deal with our planet’s environmental problems or a real option for the 1.3 billion people depending on livestock to assure their livelihood and food security?

26 Trackbacks / Pingbacks

Comments are closed.