The EU exports large quantities of milk and poultry to Western Africa. An even bigger focus on efficient commodity production in Europe might seriously hamper the status of Ghana as an emerging economy.

Introduction

The Republic of Ghana sits on the Atlantic Coast and borders Togo, Côte d’Ivoire, and Burkina Faso. The country has a population of about 29.6 million inhabitants and consistently ranks in the top three African countries for freedom of speech and press freedom, has professional broadcast media and an expanding economy. According to World Bank data Ghana’s three main export commodities are oil, gold and cocoa. Economic growth outside the oil sector is expected to accelerate as the government’s new policies in the agriculture sector and the promotion of agribusiness begin to take effect.

In 2019, the Dutch Embassy in the Ghanaian capital Accra commissioned an extensive study to chart growth opportunities in the poultry sector. According to the report, Dutch companies could make hefty profits from selling technical equipment and cheap feed to farmers in Ghana, or gain a business foothold in Africa themselves, using the Ghanaian economy, heralded to be a true beacon of regional development, as a home base. ‘Gaining the world’s confidence with a peaceful political transition and a grounded and firm commitment to democracy has helped in expediting Ghana’s growth in foreign direct investment in recent years,’ the embassy report reads. Furthermore, the study finds that Ghana’s ‘agriculture sector is expected to grow by 7.3% on the back of the government flagship programs in the sector which will enhance performance in the crops and livestock sub-sectors.’

Active government policy

The government of Ghana puts in a lot of effort to draw in foreign investors. Processing businesses are given a five-year tax holiday, agribusinesses can expect tax rebates, and custom duty exemptions have been put in place for agricultural and industrial machinery. The Dutch Embassy stresses that there are ‘specific investment opportunities’ for the production of improved seeds, fertilisers, pesticides and weedicides and for companies to produce and install cold-chain equipment on farms. It also sees growing potential for cash crops and livestock to sell on African and European Union (EU) markets.

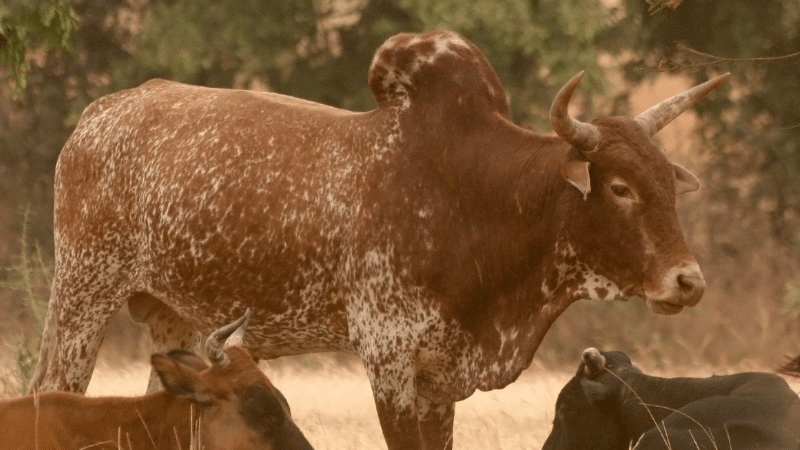

Poultry, the report continues, is one of the sectors with the biggest development potential. However, consumption patterns of households inside Ghana are still heavily weighted towards imported frozen poultry products. Most of the chicken meats in supermarkets and stores is imported from the United States, Brazil or the EU. Foreign produce is cheaper than local poultry, making it difficult for Ghanaian producers to compete and benefit from the growing urban demand for chicken meats in the entire region of Western Africa. ‘Ghana is still an agriculture-based economy,’ poultry farmer Anthony Akunzule explains. ‘The sector employs up to 65% of Ghanaians in general. But farming is especially important in rural communities, employing about 97% of the population. Poultry has the highest turnover and its short cycle of production is an important key to fast income generation for otherwise poor farmers. But European exports of frozen chickens to Ghana negatively affect the potential performance of the poultry industry.’

In 2013, the government in Accra removed customs duties on inputs like feed, drugs and vaccines to try to stimulate local poultry production, and has worked towards better access to veterinary services. In 2014, the government launched the ‘Broiler Revitalization Project’ and introduced new legislation obliging traders to buy 40 percent of their chicken meats from farmers inside Ghana. In 2017, a flagship program called ‘Planting for Food and Jobs (PFJ)’ was introduced aimed at producing agricultural commodities for a new domestic processing industry – an effort to make Ghana the regional food basket it was historically, creating much needed jobs in the process. Those active government interventions seem to be paying off. According to calculations by the UN Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), in 2000, more than 58 percent of all domestic poultry consumption came from Ghanaian farmers. In 2011, that number dropped to a mere 20% – but rose again to 38% in 2016. Government data indicate increasing exports to neighboring countries like Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire or Mali between 2017 and 2020 thanks to the PFJ program. The number of farmers enrolled in the program has grown from 200,000 in 2017 to 1.49 million at present.

EU Policies

Nevertheless, major bottlenecks remain, Akunzule explains. Besides export crops like cocoa or cashew nuts, the cultivation of maize, rice, yams and cassava is important for farmers selling onto domestic markets in Ghana. Besides his own farm, Akunzule also runs an NGO called Ghana Poultry Network (GAPNET) in partnership with Veterinarians Without Borders from Canada. He is also a member of Slow Food International. According to the national poultry association of Ghana, in 2020, over 90 percent of the annual demand for chicken is still met by foreign producers. According to EU trade statistics, European farmers exported some 175,000 metric tons of frozen chicken to Ghana in 2019 – as compared to only 13,000 tons in 2003. Chicken farmers losing their livelihoods to cheap EU imports often embark on a dangerous journey across the Sahara to cross the Mediterranean Sea towards Europe in search of a better life. Akunzule: ‘With globalization, European agricultural policies influence Ghanaian agriculture and will keep doing so in the future. This is especially the case of fruit and vegetable exports from Ghana to the European Union. In recent times, there was a ban on Ghanaian fruits due to chemical residues issues. But EU policies also slow the growth of our poultry industry and the exports of quality day-old chicks from the EU to Ghana affect operations of local hatcheries.’

Poultry is not the only sector and Ghana not the only country harmed by European exports to West Africa. After EU milk quotas were removed in 2015, markets in Europe were left awash with milk, sending prices tumbling down and forcing EU producers to seek out export opportunities. In particular the export of fat-filled milk powder has since then risen especially, reaching a total of 276,892 tons in 2018 – a 234% increase in ten years, according to data gathered by the European Milk Board (EMB). Global players such as Danone, Arla and FrieslandCampina have since increased processing capabilities in West African countries such as Nigeria and Côte d’Ivoire, providing the whole region with cheap dairy produced there and drowning out local farming communities in Ghana or Burkina Faso in the process. In a joint statement published in April 2019, the EMB and various African producers’ associations (representing nearly 50 million livestock keepers in the region) sound the alarm: ‘Local dairy development can contribute substantially to the sustainable socio-economic development of often fragile and marginal rural areas, and to more security, peace and regional cooperation. Local systems of mini-dairies, collection centres, local industries and local distribution networks provide consumers with high quality local dairy products.’ But instead: ‘attracted by a growing West African demand, European dairy companies are investing heavily in processing and marketing to find new outlets for their surpluses of various milk powders. They export from Europe, and import into West Africa skimmed or whole milk powders to Africa at a low cost. It is impossible to face this unfair competition.’

Political solutions

For the international farmers’ alliance the solution is political, they write. African authorities should raise import taxes, implement targeted VAT-exemption measures on local milk, reinforce market transparency regarding re-fattened powder blended with vegetable oils, and oblige foreign investors to buy milk locally: ‘the massive export of re-fattened powder blends with vegetable oils is the most harmful consequence of a failed European policy. A policy that pushes to produce more and more at the lowest possible price, leading to successive price crises.’

But considering Ghana already charges import duties on poultry that still damages its domestic markets, European policies facilitating cheap commodity exports, centred around the EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), should also be scrutinized, the EMB suggests. The EU could consider halting the promotion of milk exports, and internally should allow European producers to benefit from prices covering their production costs and adopt measures to manage the supply side of European dairy production in the event of a crisis. This in turn, the EMB writes, would avoid the structural cyclical overproduction which now ends up on African markets.

In 2018, the European Parliament for the first time commissioned a report to research such external effects of European agricultural policies. Professor Alan Matthews of Trinity College Dublin also co-authored a report about the external dimensions of the CAP – this time requested by the European Committee of the Regions. Focusing on the exports of milk powder, poultry and processed tomatoes, his study surprisingly concludes that, although the CAP continues to have a production-stimulating effect inside the EU, the direct impact in developing counties is relatively small. ‘Take a look at the case of poultry. In the EU poultry is a high cost activity and still we have all these cheap exports,’ Matthews explains. ‘From a purely economic point of view that doesn’t make sense. So you need to take an exact look at what is being traded. The EU mainly exports dark chicken meats, for the simple reason that European consumers don’t prefer to eat those parts of the bird, while African demand for cheap protein is growing. So, industrial chicken producers in Europe are trying to at least get some value for produce they wouldn’t sell on their home markets anyway. The low value the EU exports at certainly means trouble for local producers in Ghana because it depresses prices on African markets. But you have to be really careful which policy you target, because in this case, the CAP is not to blame.’

Wrong focus

Also in the case of milk, recent export growth has been mainly the result of the elimination of milk quotas and of product innovations, Matthews stresses: ‘What we found was the increase in exports of fat-filled milk powders was driven by a period of extra-ordinary high butter prices. For decades butterfat was in the doghouse because it was deemed unhealthy. But then suddenly nutritionists rehabilitated butter and prices shot through the roof. Cheaper vegetables oils particularly palm oil have since then been used in milk powders, which is why exports increased. That certainly can be a threat to local dairy industries. But it has nothing to do with CAP as such. To find a solution, you have to focus on the right problem. I would suggest organizing roundtables involving Ghanaian producers, some of the traders, processors and the local government, back them up by EU funding to write a dairy strategy that would work for Ghana first. Because of course you can’t build up local supply chains when your electricity is gone half the day.’

Reflections on the reform of the Common Market Organization

On the European side, the overproduction of milk would require a more structural look at the agricultural system. The Common Market Organization (CMO) is the framework of market measures under the CAP. Following a series of reforms, all separate measures were codified in 2007 into one single CMO, covering all agricultural products. In October 2020, the European Parliament again voted on a whole range of CMO amendments. In a news bulletin analyzing that vote, the EMB expressed disappointment at the rejection of amendment 277 for compulsory production reduction as an instrument to deal with dairy crises – keeping solutions primarily in the realm of the market instead of capping overproduction. ‘Strong agriculture lobbies exist in Europe as well as in developing countries,’ Matthews comments. ‘Consumer demands in urban areas in Africa are growing at lightning speed and EU produce gives access to cheap protein that many low-income households would otherwise not have. So, I am reluctant to say we should ban cheap European exports to Africa. What we need is for African governments to build and develop local supply chains as markets are growing. Companies have the responsibility to do so and European governments must consider how exports influence those development paths.’

Download this article as a PDF

This article is produced in cooperation with the

This article is produced in cooperation with the

Heinrich Böll Stiftung European Union.

More on CAP Strategic Plans

CAP Performance Monitoring and Evaluation Framework – EP Position

A Rural Proofed CAP post 2020? – Analysis of the European Parliament’s Position

CAP Beyond the EU: The Case of Honduran Banana Supply Chains

CAP | Parliament’s Political Groups Make Moves as Committee System Breaks Down

CAP & the Global South: National Strategic Plans – a Step Backwards?

CAP Strategic Plans on Climate, Environment – Ever Decreasing Circles

European Green Deal | Revving Up For CAP Reform, Or More Hot Air?

Climate and environmentally ambitious CAP Strategic Plans: Based on what exactly?

How Transparent and Inclusive is the Design Process of the National CAP Strategic Plans?