Czech farmer Terezie Daňková raises cattle and sheep on a 450 ha. ranch in Southern Bohemia. She rents most of the land she farms. Every year the shape of her farm shifts a little when the tenancy agreements are renewed in a dizzying dance involving over 100 different landowners.

Agroforestry offers benefits for animal welfare and soil fertility. Terezie is not only a farmer but also a member of the committee that is preparing agroforestry for Czech law. And that is why Louise Kelleher spoke to her about the Kafkaesque barriers to agroforestry in the Czech Republic, the subsidies conundrum, land tenure and the disproportionate number of Czech farmers who work on the farm, compared to non-farming landowners. Often the city-dwelling grandchildren of those who originally worked the land, the present-day landowners have a very different attitude to land use.

The issue of renting farmland is a nationwide problem, and poses particular challenges for agroforestry, which requires a 20-year commitment that is hard to secure with a standard 5-year lease agreement.

Terezie Daňková unpacks this complex issue as it affects her farm. In conversation with Louise Kelleher.

“No trees in the pasture”

The reason I even started thinking about this idea at the beginning of May 2016 or 2017. It was a very, very hot April. April is the month when most of my calves are born and they’re not on the farm but out on the pastures. That year on the 30th of April the snow came unexpectedly. With that a new problem arose.

The problem wasn’t the calves that were born in the snow; the problem would be those that were born when the temperature was 25°C. Although it sounds strange the brain of the calves after the birth asks what the temperature is and prepares the whole body for it. But it’s very difficult for a 2 or 3 week old mammal to adapt very quickly (from day to day), especially if it’s 25°C one day and snow, wind and a snowstorm the other one.

And there were no trees in the pasture. I said to myself: “Why? Why did the Ministry of Agriculture ask me to cut down all the trees in the pasture?” So I found out it was possible to have trees in the pasture but the Ministry typically doesn’t allow it. Since then the situation is a little bit better because a lot of farmers have had the same experience as me and asked for the trees in the pasture. But agroforestry could bring a real change.

“I depend on these subsidies”

Our farm is in the mountains. We have nearly no fields due to the natural conditions. We have meadows and pastures. The subsidies are paying for the pastures where no plant is higher than 30 cm. The price for our animals or our meat is around 22-23% of our income and the other part is the subsidies. I am now rebuilding our stables, and taking blood from my animals to find out which microelement they are missing.

If I do everything I can with ecological farming and if I do it really perfectly and nothing goes wrong I could have 28% of income from produce. But it would never be 60%. So I depend on these subsidies.

If in the new agricultural policy (CAP) 10% of our farm could be natural, it would be perfect for me, it would solve a bunch of the problems. These 10% could be filled by wetland or trees.

“I have 119 people who rent me land”

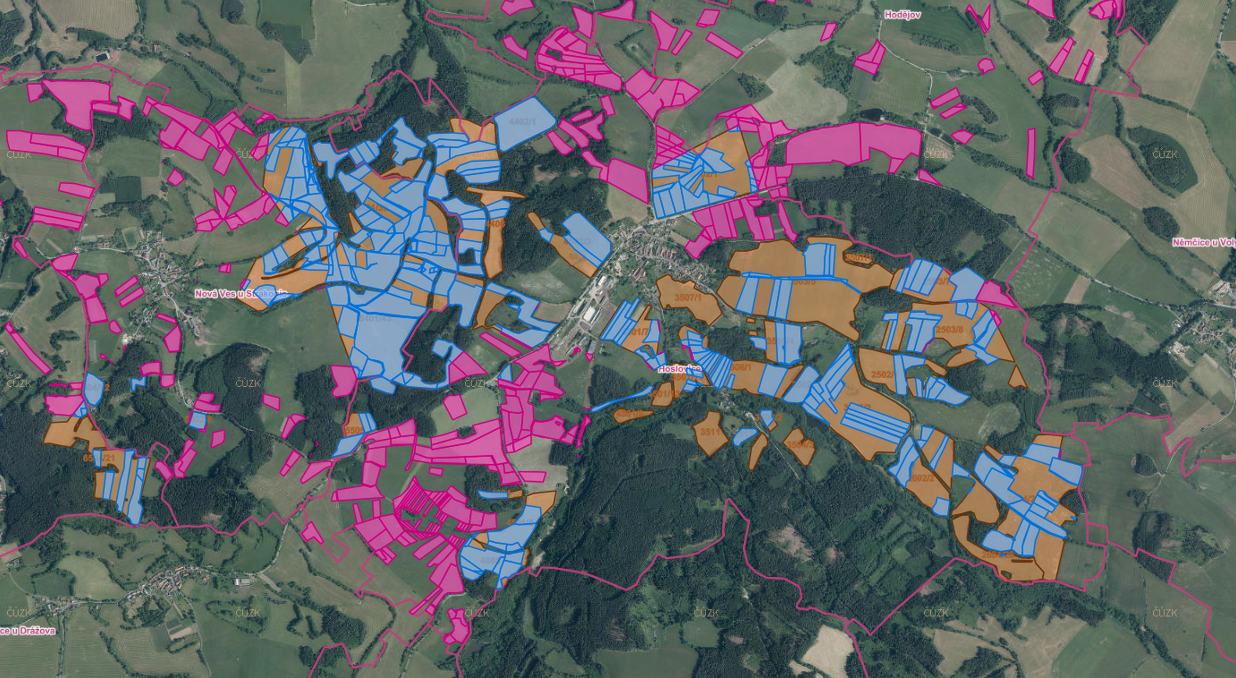

So that’s one part of the problem. The second one, which is specific to the Czech Republic, is renting land. In the Czech Republic around 72-73% of agricultural land is rented.

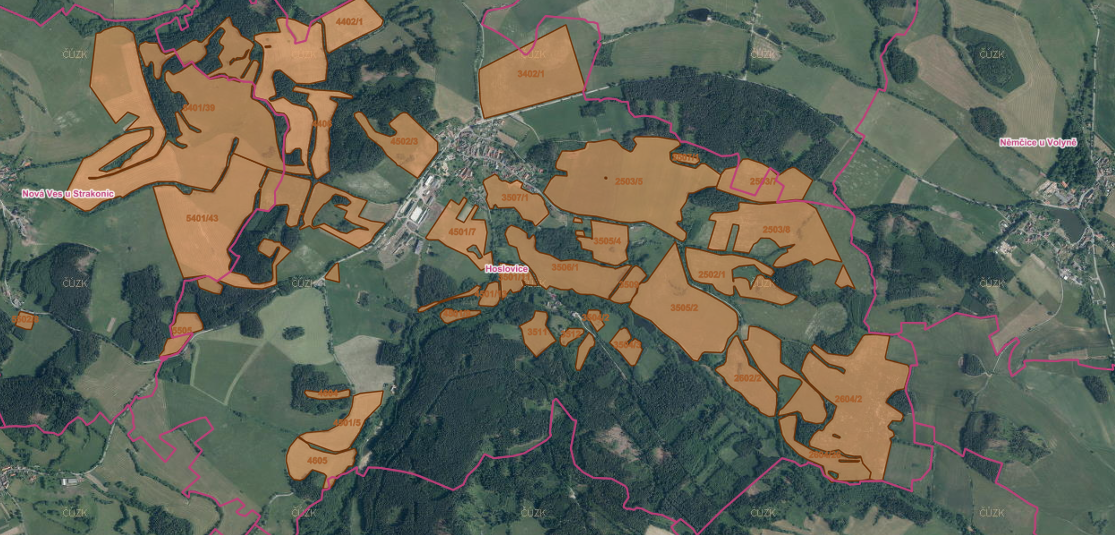

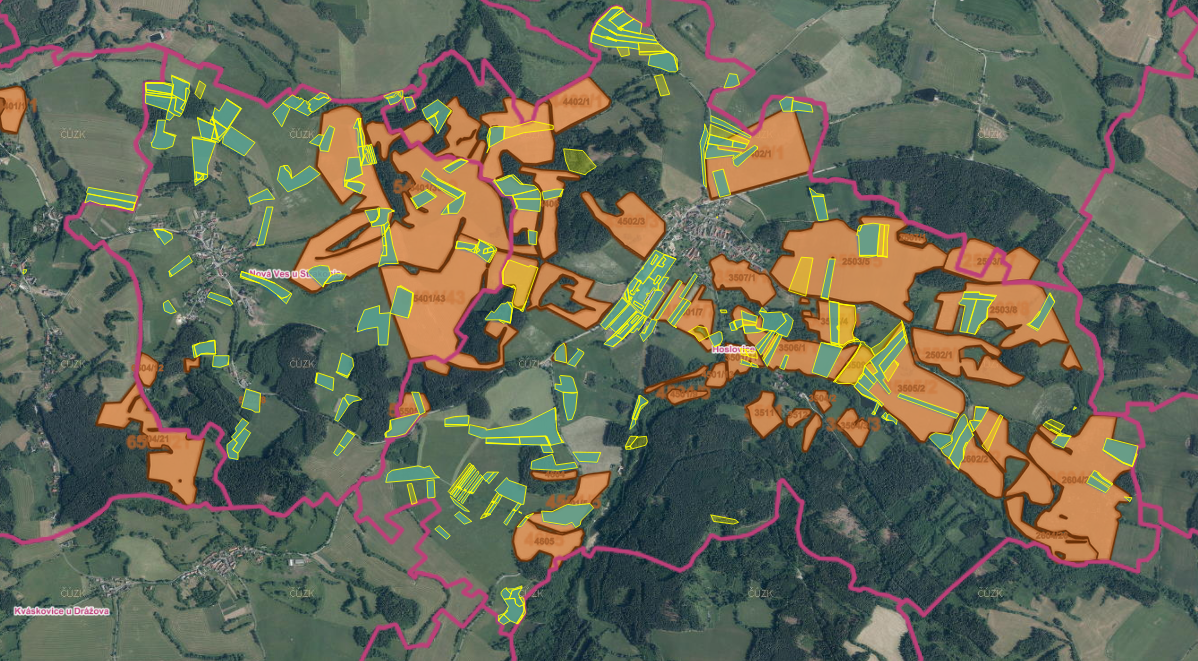

Each piece of farming land is registered in parcels a few meters long and each one is owned by somebody different. The land is so fragmented that it is impossible almost everywhere to turn a tractor on your own land. We deal with this by exchanging land between farmers, which can really complicate things.

I personally have 119 people who rent me land. With each of them I have to make a deal and sign a contract. I have to also cooperate with 15 other farmers around me and swap land strategically. I had to buy special software (Clever Farm) because it’s impossible to keep it all in my mind.

In the 90s people cared more about the land they owned and that someone was taking care of it than they did about money. So they wanted just a small rent in exchange for maintaining it. Now the landowners are looking for more and more money. They are also checking their land on the internet. So when you swap the land with another farmer, for whom it’s strategically better, and they see that online, they are angry that you are not the one who is farming on it.

There are more and more disagreements nowadays. I spend my life trying to solve all these problems in meetings, which aren’t held as often as they should be. Moreover, usually these meetings are full of shouting and fighting and I am often the only woman at these meetings, which is not easy.

New generation

It’s a new generation. When I was my daughter’s age the old women nearly kissed my father’s hand because he was taking care of the farm and village life. Nearly 100% of this village voted for my father to take care of this land.

Now those great-grandmothers are dead or too old to deal with this. I am sometimes speaking with the great-grandchildren of people who spoke with my dad 27 years ago. These people were never really working on the land and they don’t have any knowledge of what it requires to take proper care of it. They just think they have a chicken and I have to bring them the golden eggs.

In the 90s there were real meetings. Now they vote by lease. There are no meetings anymore. Two or three times a year I invite the landowners to our events, like the rodeo and spring turning pasture, but it is not enough. This I have been doing because it’s impossible for me as a mother to spend an evening with each of them (it’s 120 people – I would do nothing else!). Around 20 of the landowners usually actually come. Some of them don’t even live in the Czech Republic and they come from around Europe such as Germany or Austria.

Impossible to plan(t) trees

After three decades of farming I have a first place where I’m planning to have agroforestry. I am planning agroforestry only on my land because it needs 20 years of growing. So I need to start it on my land now. And where I am planning to have this for all eternity.

Farming on rented land comes with its perks especially when you need subsidies, because for that, there is a number of over-strict rules. For example you have to have 100 trees per hectare. It’s impossible to do so when the shape of my farm changes nearly every year because of renting land. So if I start agroforestry at some point in the layout and then someone decides not to rent me the land it won’t add up and I will lose the subsidies because of it.

The state of letting or sub-letting agricultural land is a common problem for most of the farmers in the Czech Republic. That’s why I am asking the government for the biggest allowance to change this.

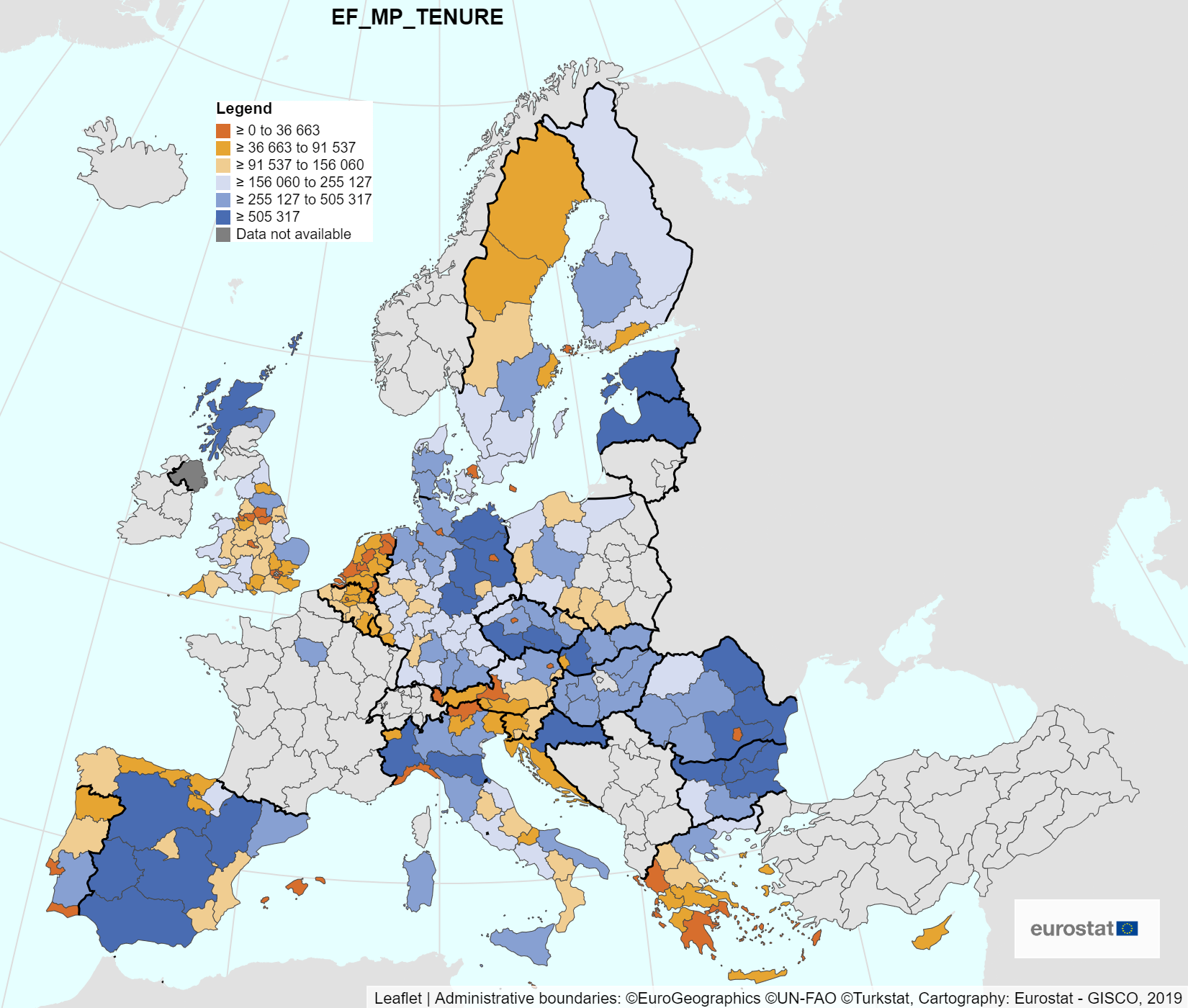

It is important to explain our situation to the EU because it is soooo unusual. My guess is that the percentage of rented land in the Czech Republic is the biggest in the whole EU. It’s definitely more than 70%. So when we speak about a lifelong decision like agroforestry, it becomes a crucial problem.

Finally I would like to say that land fertility and animal welfare are important and needs to be taken care of.

Agroforestry is one form of a perfect solution. If landowners and public administration help farmers to establish agroforestry, we can accomplish a great deal.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

More on the Czech Republic

Letter From The Farm | Freedom, Forgotten Places And The Future Of Farming

Czech Republic | COPA No Longer Defends Interests of Majority of Czech Farmers

Letter From The Farm | Half The Price Of Your Food Is Paid By The EU

Letter From The Farm | A Conscientious Objector to the Meat Industry

Czech Republic | “No Forests, No Water, No Future” – Part I: Bugs in the Ecosystem

Czech Republic | “No Forests, No Water, No Future” – Part II: Moving On from Monocultures

Trouble With The Neighbours: Living Next Door to an Agri-Giant