Is the core message of organic farming in danger of being outflanked – on both sides?

Much like in politics, where the centre is under pressure from the populist left and the populist right, organic farming is challenged on both sides.

The rules imposed on conventional agriculture, in some cases, make organic and conventional more alike. However organic is also spawning more radical alternatives, alternatives like biological or regenerative farming, which seem to have all the movement momentum, while eschewing certification – throwing out the biodynamic baby with the bureaucratic bathwater?

There is an ongoing issue with copper and its use in general, but in organic farming in particular. For certain EU regions, reapproval for another seven years was granted recently. “A maximum of 28 kg of pure copper per hectare can be used for crop protection purposes during this period. This corresponds to a maximum of 4 kg of copper per hectare per year with a smoothing mechanism over 7 years…However, Member States will have the possibility to set annual maximum limits if they don’t want to make use of a smoothing mechanism” IFOAM EU reported.

With inter-EU trade in foods, and the use of certified organic ingredients in the food processing industry, much fruit, veg and wine on our shelves comes from these approved regions of the central and southern EU.

even countries elsewhere in Europe, such as Ireland, ban and then open up the availability of copper to organic farmers over the years, most recently in 2017. After announcing a ban on copper products for 2017, a follow up lifting of said ban in the case of a copper fungicide was announced in June 2017 by the Department.

There is work being done to reduce copper use, and of course the conventional sector has its own vast array on biocides when compared to the very small number allowable in organics; moreover organics tends to be about techniques rather than inputs. However, much like the stubborn issue of monogastric feeds having a small % of conventional ingredients, the organic sector needs to address this issue properly, and not just carry on regardless, hoping the occasional conference or EU funding initiative will sort the problem out.

One of the unfortunate consequences of increasing climate extremes is that it gets harder and harder to farm within the EU environmental rules. Parts of Europe saw greening rules relaxed over the drought, while peat bedding is now allowable for the winter on organic farms.

The conundrum is that all of these measures seem like important emergency measures, but the emergencies keep coming and coming. From a climate change perspective, using peat in this way is a disaster; in terms of the image organic farming presents to the world, it cannot be seen as a positive.

Targeted research and practical measures need to be put in place to offer better options than copper fungicides and peat bedding for organic farmers for the seasons ahead.

Meanwhile, more limits are being imposed on conventional farmers. Not just with various biocides being banned, such as neonicotinoids, but also limits being imposed on their model of farming. The EU will use GM regulatory rules in the emerging area of gene-editing; further restrictions will be imposed on mineral fertilizer use in the years ahead too.

Mineral fertilizers used by conventional farmers in the EU currently have excessive levels of the human and environmental toxin cadmium. Now, a 60 mg/kg limit will come into effect in 2022, and further restrictions may come in in 2026.

No till farming gets great press for positive treatment of the soil and its stored carbon: no till in its purest form is difficult for organic farmers, with min till being the closest variant. No till crop production is still in its infancy in western Europe, whereas it is even more the main approach in the Americas.

And finally, on the other flank, biological farming and regenerative agriculture seem to have a far more compelling story than organic farming right now.

Of course, they both borrow from the old organic handbook, but they seem to be post organic-baggage, but pre-organic’s bureaucracy – a nice place to be. A certification scheme for regenerative organic farming is emerging, but still, using self-declared soil building eco credentials is far less arduous than the bureaucracy of the organic system.

So what is organic’s main message? Somehow organic must combine scale, trust and movement friendly environmental meaning, without being the new kids on the block anymore.

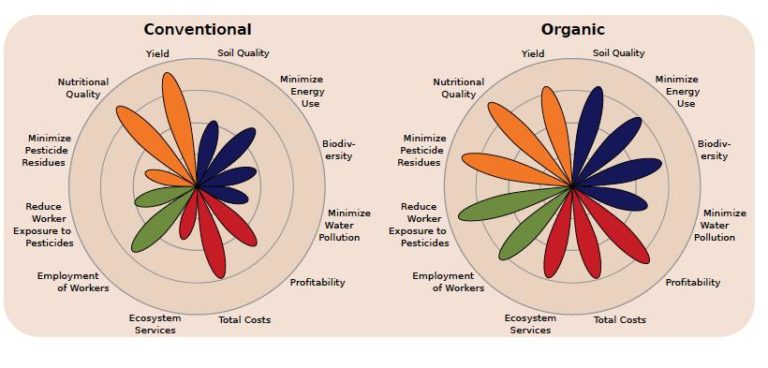

On balance, organic still scores really well in sustainability terms – beating conventional in 10 out of 12 categories, and scoring similarly in the 11th – but it’s certainly no time to be complacent.

A shorter version of this article appeared in the Irish Examiner’s farming supplement.

More