Marine life in the Baltic Sea is drowning in algae. Largely to blame is nutrient run-off from intensive pig producers, thanks to a model of factory farming largely unchecked by EU regulations. Experts are calling for closed nutrient cycles to combat eutrophication – and engaging with the polluters to find solutions. Hans Wetzels reports from Poland.

It’s a harsh winter’s day in Poland as Maria Staniszewska steers her car through a dense forest. Wooden cabins advertise classic Polish pierogi and beet soup. As a scientist Staniszewska is heavily involved in researching the effects of intensive agriculture on dead zones in the Baltic Sea. “EU legislation would be useful to address this problem,” she explains. “But that wouldn’t change the fact that eutrophication originates on large animal farms. Nutrient cycles should be closed at farm levels and meat consumption reduced if we ever want to solve this.”

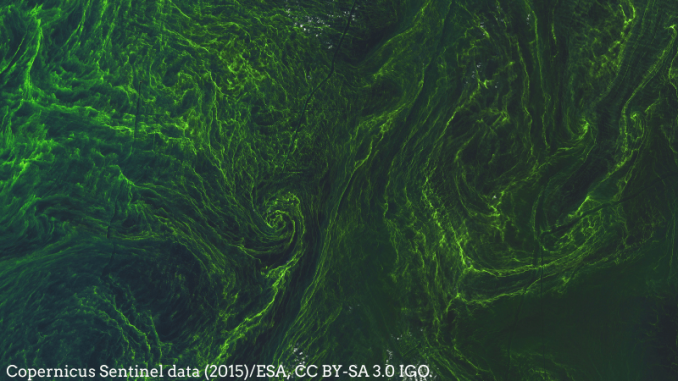

Eutrophication is a complex process – connected to fertilizer run-offs from the land, phosphorus leaking into the sea, overfishing, intensive pig farming in Poland, and thus also to the CAP. So how does it work? Usually, nitrogen levels in the Baltic Sea are highest during wintertime. The excess nitrogen makes algae bloom, leading to a thick layer of unappealing green slime coating beaches in July and August. Soon after, the algae die, sink to the bottom and start to decompose. An increasing amount of decomposing algae uses up most oxygen in the water, while other substances, like methane, ammonia and hydrogen sulfides, are released back into the water, creating underwater dead zones devoid of life.

A sensitive sea

Dead zones are not unique to the Baltic Sea. The worldwide number of marine areas where algal blooms have robbed waters of oxygen has quadrupled over the past 50 years. The Gulf of Mexico’s dead zone has grown to a staggering 22 730 km². Research done with underwater robots (2015) suggested that the world’s largest low-oxygen zone is located in the Gulf of Oman, south of Iran, where fish, marine plants and other species are unable to survive in an area as large as 163 000 km².

In comparison, the Baltic is a small sea – stuck as it is between the Polish northern coast, the Scandinavian peninsula and the three Baltic republics. Because it’s almost entirely surrounded by land it has only low levels of salinity and the water is relatively stagnant. “Those factors make the Baltic Sea so sensitive to pollution,” Staniszewska explains. The Baltic dead zone has expanded from a small patch of low oxygen off the coast of Sweden a century ago, to an area spanning 59 570 km² today. “The condition of the sea has deteriorated dramatically. Areas on the seabed with reduced oxygen contents have grown twelve-fold, spanning an area from southern Sweden to the deep water basin north of Gdansk in Poland.”

The dose makes the poison

The main reason for the spike in eutrophication in Baltic waters is agriculture. In the twentieth century mineral fertilizers and chemical pesticides were introduced. Since then farmers no longer have to depend on animal husbandry for fertilizers and have become fully dependent on chemical inputs. CAP measures, largely based on hectare payments or output support, exacerbate exactly those forms of farming responsible for excess usage of fertilizers and pesticides, causing increasing run-offs into groundwater, rivers and seas. Staniszewska explains: “Even most organic farms in Poland do not have any animal husbandry, so they are increasingly dependent on the purchase of external fertilizers. Run-offs from nitrogen and phosphorus compounds end up in the sea, resulting from over-usage relative to the yields. Elements like nitrogen are necessary for plants and soil microorganisms. But their excess is very harmful to aquatic ecosystems.”

A 2018 study published in the journal Biogeosciences details a 1,500-year history of low-oxygen conditions in the Baltic Sea. Occurring naturally at a smaller scale, since the 1950s algae blooms have mushroomed at an alarming rate due to excess nutrients. Rising deep-water temperatures are predicted to worsen conditions, while wastewater from sewage-treatment facilities and overfishing of Baltic cod have intensified the eutrophication problem, explains Conrad Stralka, a reseacher for the environmental foundation Baltic Sea 2020. Cod eat sprats, a species of fish that in turn feeds on the zooplankton that eat the algae causing the eutrophication. A vicious cycle set to worsen as the dead zones endanger deep-water breeding grounds of the cod, Stralka says: “For decades nutrients like phosphorus have been leaking into the sea. Usually, algae blooms in deeper water and then goes up to shallower waters only a couple of meters deep. When the plants die they sink to the bottom again where oxygen is used up. In practice that means that all life on the sea bed dies. The effects of eutrophication are in turn amplified through the impact of commercial fisheries on the Baltic ecosystem.”

Problem-solving with polluting pig farms

To a great extent the intensive pig farms lining the Polish coast are to blame for the dangerous eutrophication in the Baltic Sea, Stralka says. Unrestrained by EU policies, these factory farms have been stocking numbers of animals far too large for the area of agricultural land owned. “What we lack in Europe is phosphorus regulation,” Stralka explains. “In countries like Germany or Poland there are no rules at all for, for example, phosphorus, whereas in Sweden or Finland you have only voluntary guidelines. Poland did, however, invest heavily in some modern wastewater plants. What we really lack is decent European laws to regulate countries like Poland or Denmark that have large scale agriculture bordering sensitive seas like the Baltic.”

To come up with solutions instead of waiting for EU regulations to be approved, Stralka and his colleagues have started cooperating with such large-scale Polish farms themselves. “We have done projects with industrial pig farms in Poland where 60,000 pigs are produced each year,” he explains. “We wanted to see if it’s even possible to have large-scale meat production in such a way that you could avoid leaking nutrients into the soil. The EU Nitrogen Directive states that outputs can be no more than 170 kilos per hectare of land. But in practice, you also lose nitrogen released into air as ammonia, which is a form of pollution you could decrease. Furthermore, farmers often store manure in open lagoons where it often leaks into the ground. To compensate those losses farmers buy synthetic fertilizers. You could avoid a lot of problems by developing better systems like closed storage in order to close nutrient cycles better on the farms. However, without EU regulation all that won’t structurally solve the problem of nutrient run-offs from big animal farms and it’s up to the European Commission to change those rules.”

More from Poland

Poland | The Biosecurity Battle with African Swine Fever on Farms