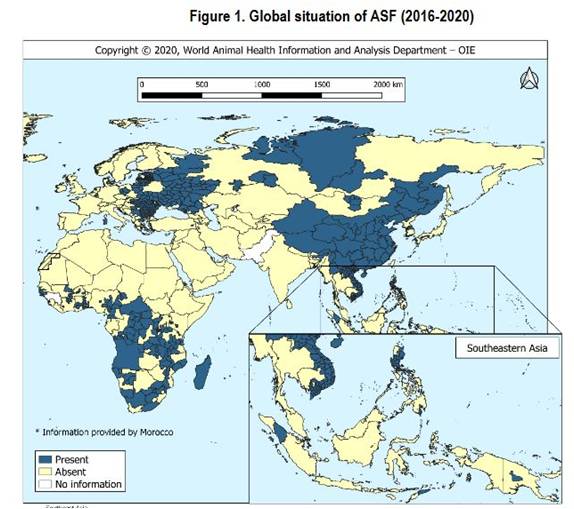

Since crossing the EU’s Eastern borders more than half a decade ago, African Swine Fever (ASF) has continued its march westwards. Igor Tomasz Olech walks us through the biosecurity measures brought in to curb the spread of African Swine Fever in Poland.

African Swine Fever (ASF) is an increasing threat for the EU, the world’s second biggest pork producer after China. Poland is one of many member states from the former Eastern Bloc that were hit hard by the virus. Pork exports were severely impacted, with non-EU states shutting their doors to Polish meat. Previously a major exporter to China, Poland was unable to profit from the ASF-induced crisis in the Chinese pork industry.

Over several years of struggling to contain ASF, Poland has introduced a number of legal and institutional regulations. Since a vaccine is a distant promise, producers, government officials and hunters have tried to curb the epidemic by implementing biosecurity measures and by culling wild boars.

In this article we’ll look at how effective biosecurity measures have been in fighting the virus in Poland.

Early restrictions

When the disease began to spread in Poland in February 2014, early restrictions included locking animals in separate rooms, and a ban on pork from regions in which the disease was identified. The virus spread to livestock very quickly – within six months of the discovery of the first infected dead boar, there were already two outbreaks among domesticated pigs.

In July 2014 agricultural minister Marek Sawicki announced that all pigs within a 3 km radius of the outbreak were to be disposed of, while all farmers were to be compensated according to market prices. Moreover, farmers were to be compensated for the next three years to allow them to switch to production of other animals. “These are small farms, so it is difficult for them to make a living just from plant production,” said Sawicki.

Poland’s biosecurity plan

The main front of Poland’s fight against ASF is its biosecurity program. It was implemented on the basis of a regulation of the Minister of Agriculture, and prepared by the Veterinary Inspection. Polish biosecurity regulations have since been updated on several occasions, with the government bulking up existing biosecurity regulations with specific measures regulations to target ASF.

In late April 2015 a comprehensive biosecurity plan was introduced in regions where infected boars had been found (English translation here). But a combust law was only introduced in May 2015 — more than a year after the first infected boars were found in Poland.

The biosecurity plan defines “infected” areas (a 3 km radius around the epicentre of the outbreak) and “vulnerable” areas (a 10 km radius around the point of outbreak). Pigs in infected areas are to be liquidated – unless the farm complies with biosecurity regulations, and pigs within vulnerable areas are to be under strict observation. Transport to and from vulnerable areas is also prohibited for a period of 30 days. The pig herd could be reintroduced after the quarantine period.

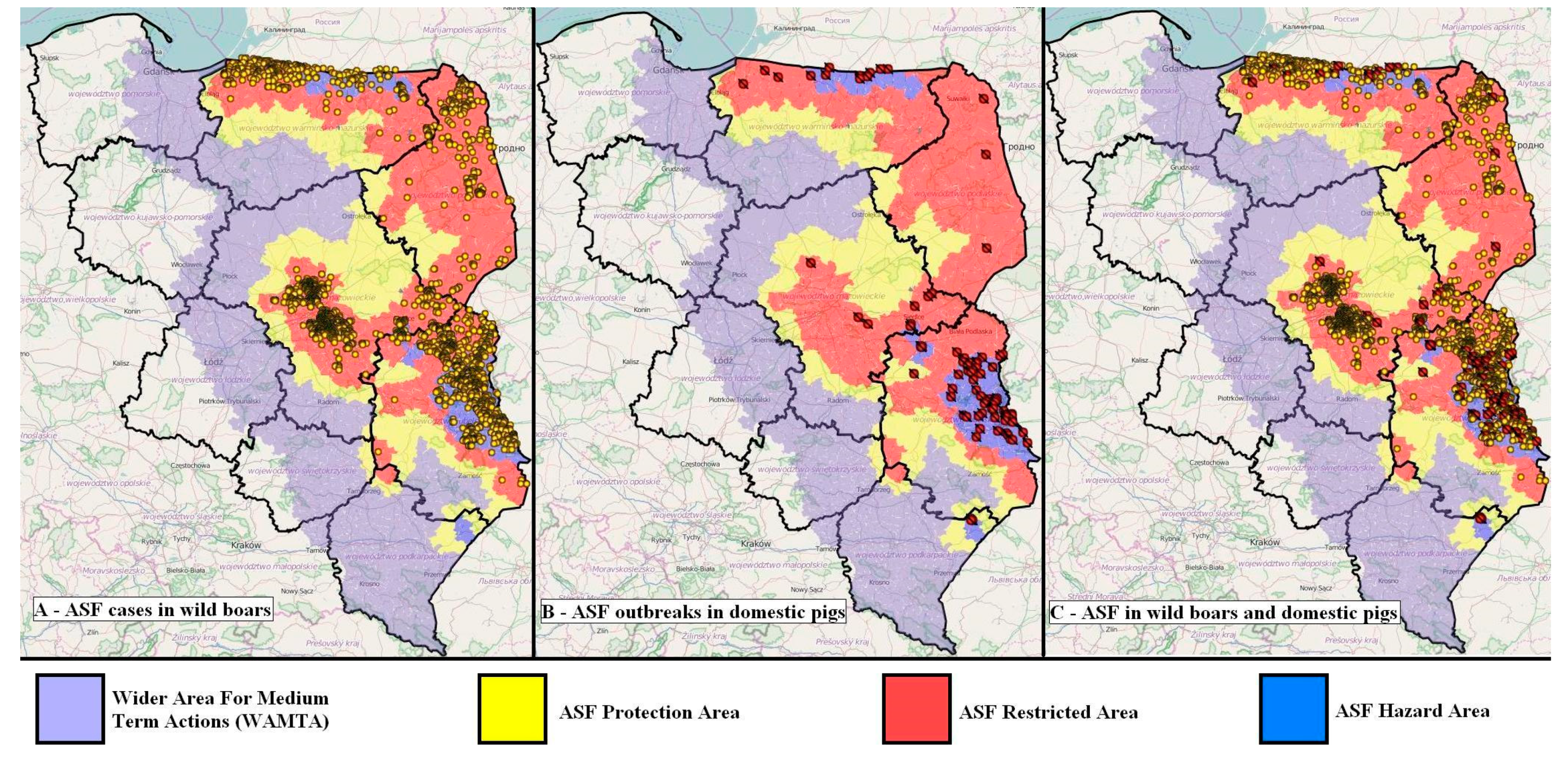

Geographic demarcations

The Wider Area for Medium Term Actions (WAMTA) was a new “layer” added on top of the existing Protection, Restricted and Hazard areas. Spanning a swathe of the eastern Polish border (see the picture above) WAMTA extended 50km to 200km deep into Poland, depending on the threat of the epidemic spread. Within the first year (from 2014 to 2015), the boar population within the WAMTA bordering with Belarus was reduced by one fourth.

The demarcation of these zones can be problematic, as migration of boars is not determined by administrative borders of regions. In late August 2019, Ardanowski announced his opposition to the EU’s proposal to create protection zones according to the administrative divisions of Poland, stating that these zones should be divided according to natural barriers, i.e. highways, rivers etc.

Fencing

As the disease may be spread by wild boars, it is crucial to separate farms from forests inhabited by wild animals. Boars are often attracted to grain growing on farms. Whether the virus can be spread through crops is disputable. In 2014, the General Veterinary Institute announced that spread of the virus through wheat or through corn is “theoretically possible”, but with “very low probability”.

Despite that, corn farmers were troubled by the possibility that pig breeders would cease to buy corn from regions threatened by ASF. For instance, in November 2016 Polish pork producers (e.g. Management Board of the National Council of Agricultural Chambers) and veterinarians appealed to the Polish government to cease imports of the wheat from Ukraine, as “during the harvest the grain can have contact with ASF-infected boar carcasses and faeces infected with the virus”.

According to website Świat Rolnika (Farmers’ World), “the ban of imports would benefit Polish growers, who have been complaining for months about spoiling the market with cheap grain from the East”. In the current trade system, even such large grain producers as Poland may be unable to compete with imported wheat. As such it may also be that farmers used the epidemics to frame their problems, attempting to capitalize on relatively disconnected issues.

Sanitation of the supply chain

Workers on the farm have to be familiar with hygiene measures, and access to external visitors is prohibited or restricted. ASF began to spread in western Poland, closer to the German border, in the country’s main pork-producing region Wielkopolska (Greater Poland). There was a suspicion that ASF was carried by faeces on a shoe — probably by a farmer or hunter. That is why the government encourages usage of protective clothing, periodic disinfection of barns, as well as isolation of farms from rodents and household animals, which could easily spread bodily fluids containing the virus. Their feed should be of identifiable, non-animal origin.

There were also plans to inspect the meat at the end of the supply chain – just before it is brought to customers. In 2016 regional vets discussed not only carrying on with farm controls, but with market controls in the threatened areas as well.

Small farms the most vulnerable

According to Radomir Bańko, the district vet in the city of Biała Podlaska, all the ASF outbreaks happened in small farms that raise between 3 and 14 pigs, and lack fences, gates or properly isolated farm buildings. Close proximity of pastures to forests also could be the reason for the spread of the virus on small farms, as some parts of boar’s faeces could have been brought after foraging.

According to Polityka magazine, the current government is only simulating actions against ASF, as it does not want to alienate small farmers, who mainly vote for PiS, while according to agricultural minister Ardanowski, small farmers cannot fulfill all the biosecurity standards as their farms are outdated. Polityka adds that Veterinary Inspectorates cannot always inspect small farms, as their representatives are not always welcome.

Where pig producers breach the biosecurity regulations, their farm can be liquidated without the possibility of receiving three years’ compensation.

The impact of ASF shifts production patterns toward larger, more industrialized producers: small-scale production is liquidated to the benefit of large-scale “biosecure” farms. It is even more relevant in the situation of Poland, where the dominant model is small-scale farms which have high potential to develop ecological and more animal-friendly production.

Government and EU supports: a timeline

By mid-2014 the Agricultural Market Agency had already received almost 1,500 applications for ASF compensation from farmers in eastern Poland. “The money is to compensate the farmers for the losses they have suffered by not being able to sell the pigs. The affected farmers owned 17 thousand carcasses. Poland has applied to the European Commission for special aid for farmers. The EC allocated €7.1 million for this purpose, half of which is European funds; the remaining money comes from the national budget.”

In June 2015 minister Sawicki informed that “the farms that would give up [hog] breeding for three years would receive compensation of about 50 zlotys per unit they would have bred during those three years”, while the ones which decided to keep pig breeding, were to be subjected to intensified veterinary controls.

On 29th July 2016, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development issued new amendments to the Bioinsurance Programme to Prevent the Spread of ASF. These included changes for the years 2015 – 2018. “Two amendments to the regulation gave farmers in Podlaskie Voivodeship an additional chance to voluntarily withdraw from pig production with damages and 3 years’ compensation”.

In mid September 2016 Agricultural Minister and Vice-Minister Jurgiel and Bogucki met with EU’s Health Commissioner Vytenis Andriukaitis, who promised to financially support Polish pig farmers. In the same month, a Special Act signed by the President Duda allowed the government to buy 100,000 healthy pig carcasses from the threatened zones (for a price similar to the market price) in order to heat-process them at 120°C+ into canned goods and pâtés for the army and charity organisations. “Establishments which undertake to produce canned pig meat from restricted zones will be guaranteed to be bought out by public finance institutions. It will be procured without regard to public procurement law”.

Unfortunately, the amount of pigs ready for slaughter was far higher than what the government had anticipated. Meanwhile, the Agricultural Market Agency supported farmers with 6.9 million zlotys (ca. €1.5 million), while the overall cost of ASF in Poland to date had been 15 million zlotys (ca. €3.4m). Many processors suspended the purchase of pigs, which were already fattened over the slaughter weight, with some breeders suspending their activities. It also had an impact on wheat prices for feed.

In October 2016, at the forum of EU Agricultural Ministers, several member states supported a Polish proposal for financial support to fight ASF. Agricultural Commissioner Hogan said that the proposal was well grounded.

In early 2020 the Agricultural Ministry announced 133 million zlotys (ca. €30 million) to target ASF, and Poland will apply to the EU to contribute 23 million zlotys (ca. €5 million) toward this goal. Some of the expenses shall include: testing, storage of infected boar carcasses, and hunting down of infected boars, biosecurity controls by regional vets (as well as materials required for these), payments for reporting of wild boar remains as well as financing searches for dead boars, increase of biosecurity on borders with Russia, Belarus and Ukraine (i.e. neighbouring non-EU states), and an awareness campaign for public officials and food producers.

Not a poster child for biosecurity

Poland is not considered a shining example in the implementation of biosecurity. As we can read on the website EuroMeatNews, “Biosecurity was helpful in stopping the spreading of the virus in countries such as the Czech Republic, Belgium and, partially, in Russia but it paid no results in China, Vietnam, Poland, Romania, Ukraine, Belarus or in African countries, where it was first observed 50 years ago.”

There are various reasons for poor performance in Poland, where multiple factors were at play. First, obviously, clumsy implementation. Zoologist Prof. Elżanowski, in an interview for the magazine Polityka, criticised farmers’ negligence regarding the implementation of biosecurity measures:

“Farmers bought cheap animals, of unknown origin, introducing infected pigs into the pigsty. They traded them at fairs. They fed them with beakers and waste, while it should only be tested feed. Pigs must be kept in strict isolation, only in farms with the highest level of protection, where not even a mouse can slip and 74% of farms did not have such protection. Many of them did not even have disinfectant mats. Veterinary supervision often boiled down to uncritical acceptance of information from district doctors. This is what we need to focus on.” — Prof. Andrzej Elżanowski

With this opinion disagrees district vet Radomir Bańko, who said that the ASF spread in these farms was not a consequence of purchasing animals of unknown origin, since the documentation clearly stated that all the animals came from natural mating within farms themselves. The animals were liquidated where the virus was identified.

There are also biological and environmental differences, what makes it more difficult to copy all the solutions which were applied in, for instance, Spain. In the north, the disease is not present among Central and Eastern Europe soft ticks, which were the primary spreaders in the Iberian Peninsula. But in the temperate climate, where the decay period is longer, the virus can survive longer.

The legal factor may also help to curb the spread of ASF. Poland has amended its penalisation code for people who contribute to the spread of the disease. For example, farmers who transported pigs in breach of the biosecurity rules could be sentenced to prison for up to one year.

Too late to stop the spread

While Poland’s 2015 biosecurity plan outlined above is very comprehensive, it may have come too late to stop the spread of the virus. Indeed, weak biosecurity allowed the virus to spread in North-Eastern Poland, the Highest Chamber of Control has criticized.

ASF was discovered as early as 2007 in Georgia, where it arrived most probably from Africa. It then spread to neighbouring countries and on through Russia to Ukraine and beyond. In 2011 Poland began to monitor the situation, patrolling the entire Eastern border across a 40 km radius, and collecting samples from pigs and wild boars. The budget of the program was rather symbolic (ca. €1.25 million, co-financed by Brussels), considering that the losses for the industry amount to hundreds of millions of euros, and can even reach billions.

In 2012 the Polish Veterinary Institute recommended culling, but made no reference to biosecurity to fight the epidemic. It was not until March 2015, at a scientific conference on “Threats to the pig sector from ASF”, that the Polish Under-Secretary of State pointed toward biosecurity as the most effective method of fighting ASF.

The lesson to be learned from this should be to have a plan prepared in advance for such devastating diseases that affect the fauna and flora of the ecosystem.

By contrast, Hungary introduced anti-ASF biosecurity measures just weeks after the virus was discovered in the dead wild boar in Poland. Even this was rather late, as it had been known for years that the disease was spreading to the East of the EU. Hungary however has handled the epidemic well and has had no outbreaks among domesticated pigs.

Conclusion

Taking a look back, Poland did implement quite robust anti-ASF measures, but as can be seen now, it may have come too late. Poland did not pay enough attention to the spread of the disease beyond its Eastern border. Hungary took a similar course of action, also only after an infected boar carcass was discovered in Poland. But as both Poland and Hungary share borders with non-EU countries, they should keep in mind that they are bordering with states which do not have the means or quality standards of EU member states. Perhaps it was pure chance; perhaps an infected carcass could have been found in Hungary first. Perhaps Poland should also pay extra attention to its neighbour Belarus, which does not release data on the disease, and does not even admit it is present in the country.

Poland however was ahead of the game when it came to the coronavirus outbreak, as the introduction of biosecurity measures to combat ASF had made food producers improve in several fields.

As in China, Poland is attempting to limit its largest meat industry. In such a situation, support for farmers who would like to cultivate other protein sources could be encouraged. There have already been some efforts to increase the production of high-protein plants for feed to ensure “protein security”, initiated by representative Sachajko in 2018.

For now, the main tasks which stand before Polish pork industry are the implementation of on-farm biosecurity, and protecting forests and its wildlife.