In preparation of the Commission’s expected proposal for a new seed marketing legislation on June 7th, MEP Sarah Wiener and MEP Martin Häusling called a conference to discuss what is needed for a just transition to agroecology. The conference, moderated by President of ARC2020 Hannes Lorenzen, brought together farmers, MEPs, NGO members and Commission representatives. What’s coming: New information about the next form of seed legislation, some secondary space for agroecology, and key GMO concerns.

With Mathieu Willard

No seed, no agriculture.. But what kind of seed is key. “Which seeds for a just transition to agroecological and sustainable food systems” was thus the theme of last week’s conference. In this article, we report on the key learnings from this event and provide some of our own observations.

Seed variety is a defining criterion to enable the agroecological transition. But fewer than 200 plant species actually make a substantial contribution to global food production (out of 6000 species cultivated for food). Of those, only 9 species account for 66% of total crop production. These FAO figures illustrate the dangerous homogenisation and erosion of cultivated diversity.

The cause of this loss in cultivated biodiversity is path-dependency in industrial agriculture. Seeds adapted to intensive production are made to be completely homogenous. This makes sense within the agri-industrial paradigm: the main operating principle of those systems is uniformisation of culture conditions through the use of synthetic fertilizers and chemical pesticides. And the current seed marketing legislation is one of the main lock-ins to transition pathways outside the business-as-usual.

Right now, access to the seed market is highly prohibitive to agroecological seed systems and seed saving initiatives. Those systems are exactly the ones that produce and make accessible a variety of locally adapted seeds. The next seed marketing legislation should therefore lay the foundations for a better integration of seeds curated for generations by peasants and other farmers. But will it?

Commission hints…

Dorothée André, Head of Unit Plant Health, was one of the Commission’s representatives at the conference. She clarified what could be expected from the upcoming proposal. Here’s the short version:

- Most of the restrictions in the marketing of Conservation Varieties will be lifted, especially the quantitative or geographical restrictions. The scope will also be extended to newly bred, locally adapted varieties.

- The access to Organic Heterogeneous Material will be widened to all farmers.

- Exchanges in kind between farmers will be allowed under light conditions.

Although this feels like good news for agroecology supporters, as André highlighted the crucial importance of integrating diversity, resilience and sustainability in the regulation, she insisted that productivity was still a very relevant priority. She did not however undertake to explain how those would be compatible.

Awaited changes seem to be under consideration by the Commission. But what remains is the idea that organic production and agroecology are secondary systems. Room will be made for them to develop, but awkward questions of co-existence, of measurement and more remain. However the Commission is not yet ready to make organics and agroecology the norm.

Room for Agroecology…and GMOs?

Following André’s intervention, a discussion panel was introduced to debate the needs of the up-coming regulation proposal. And it didn’t take long for the elephant in the room to be addressed: the deregulation of GMOs.

GMOs and Seed’s marketing: converging proposals

There are crucial links between the seed marketing legislation and the legislation governing the import, cultivation, labelling and traceability of GMOs. If GMOs bred through new genomic techniques are authorised in the EU, it is the seed marketing legislation that will establish the conditions under which GM seeds will be registered in the EU catalogue to access the market.

As both proposals are scheduled for June 7th, there are concerns that they are being developed as a package. And although a revision of the seed marketing rules is urgently needed to speed up the agroecological transition, a deregulation of GMOs and their marketing throughout the EU would have the opposite effect, acting as a Faustian Pact for supporters and practitioners of agroecological farming.

Transparency and labelling

The first link to keep an eye on is the transparency and labelling about the breeding technique used to obtain a seed that would be added to the EU catalogue. But transparency is not enough for protecting farmers and breeders. Once a farmer decides to sow GM seeds, the genetic material can crossbreed with crops from neighbouring fields and effectively contaminate them, potentially making them uncertifiable in the organic system among other considerations.

This risk for contamination is even more troubling when considering the issue of patents. Companies producing GM seeds will register patents trads bred. This effective privatisation of life is an attack on morality but also a flawed interpretation of “human creation” as nobody ever really created a gene, these are cut/copied/pasted. So human creation is more like a category mistake in itself, ignoring a priori existence of genes as things in themselves.

Philosophical considerations aside, the technology could also be risky for farmers: these patented genes will eventually disseminate, making it difficult, if not impossible for them to prove that their seeds are not subject to royalties.

Criteria – and the real basis of resilience

The second link to watch closely concerns a potential list of sustainability criteria that could be required for registration in the EU catalogue. The Commission is considering adding sustainability criteria in the variety registration procedure. The list would consist of variety traits that would be useful to respond to climate change (e.g. drought tolerance is a trait that is currently being tested in Spain).

This list of sustainability traits for the registration of seed into the EU catalogue could clearly be designed to allow the marketing of GM seeds that are patented on the basis of added traits.

Such an approach completely misses the basic concepts of resilience in agriculture. No singular seed trait can be applied wherever and then provide a function. Adaptability is achieved through a vast combination of specifically adapted traits that can only be found in locally bred seeds. Local adaptation is the result of local selection and reproduction in farmers’ fields, maintaining and increasing the genetic biodiversity which provides the flexibility to address diverse environments and a changing climate.

Moreover, these traits have been built up over a long period of time, time when farmers’ careful curation and labour have been key. This approach would thus disregard the social component of sustainability, providing market access to bio-tech giants to compete with peasant seed systems.

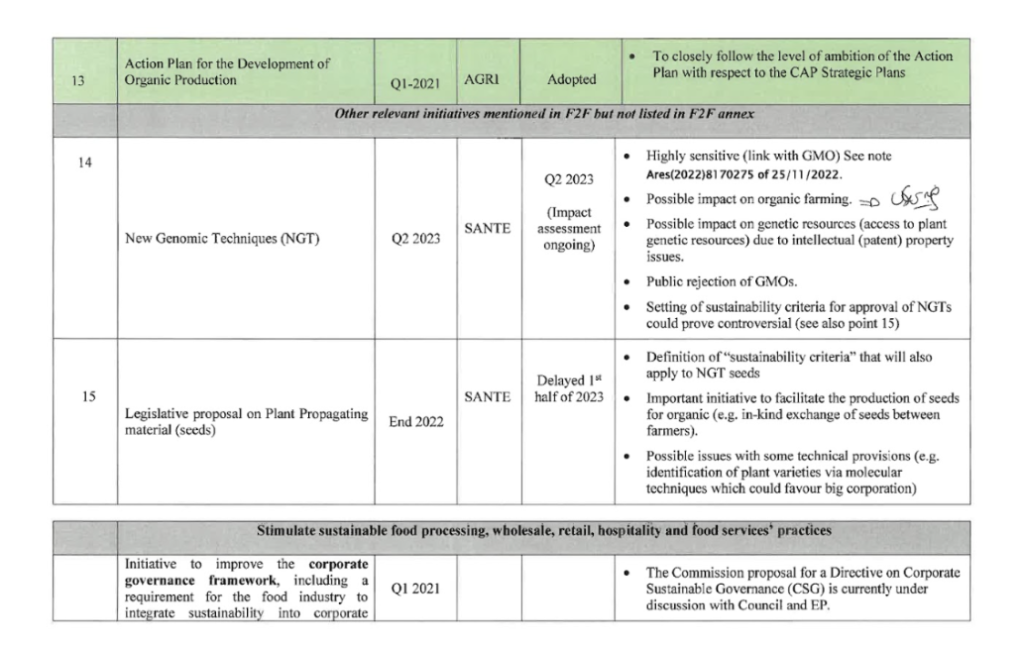

The sensitive interlinkage between those two incoming proposals is known to the Commission. This was shown in a leaked Farm to Fork document from DG AGRI entitled an “overview of the politically sensitive topics”. In a section of the document presented below, it reads that the deregulation of GMOs (NGT section) could have a “possible impact on genetic resources due to intellectual property issues” and that the “setting of sustainability criteria for approval of NGTs” and “their definition” in the legislative proposal for seed marketing “could prove controversial”.

Should we get rid of the VCU?

Most of the panel also insisted on a current requirement for registering seeds that should be redesigned completely, the Value for Cultivation and Use testing (VCU)

The VCU consists of a set of testing that is performed by national authorities on specific testing sites. The VCU protocols are established on the national level and vary from one country to another, but all place a specific focus on yield performance. Improved productivity is therefore a key selection criterion that doesn’t necessarily fit the need for more diversification and adaptability of seeds.

Another issue with those sets of tests is that the conditions often are not adapted for organic seeds. This is because the number of official organic testing sites is low and their development is slow because of high costs that Member States prefer to avoid. Moreover, the current VCU methodologies are incapable of producing seeds that would fit the needs of farmers in marginal areas. The seeds are often tested in conditions that fit the more standard, productive farming conditions. But for marginal areas such as high mountain environments, there is a need for seeds that are specifically adapted to the local climate and soil conditions.

It is unlikely that the objectives of increasing cultivated biodiversity or reaching 25% of organic production by 2030 can be achieved without changing the VCU approach. Alternative criteria were proposed by the panel, such as minimising the use of chemical input or assessing the protein and mineral content of the production. In any case, VCU testing should be better tailored to different needs.

Another idea could be to allow for more derogations from VCU testing for certain seed types. Getting rid of the VCU completely was also proposed, but Spyridon Flevaris, a DG SANTE representative included in the panel, affirmed that ditching the VCU was not on the table.

We’re Just Getting Started

If you wish to learn more about the marketing of seeds in the EU, we recommend you have a look at the new study produced by Arche Noah: EU reform of seeds marketing rules Which seeds for a just transition to agroecological and sustainable food systems? (click on image and link below) ARC2020 is now also leading the Seeds4All project, with more analysis to come. Sign up for the dedicated Seeds4all newsletter for more information.

More on seeds from ARC2020

Organic and Biodynamic Viticulture: Adapting the Vine in a Changing Climate

Catcher in the Rye: Breeding Diversity for Unpredictable Conditions

1 Trackback / Pingback

Comments are closed.